Authors: Victoria Charles and Irina Shuvalova

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ivan Shishkin (Parkstone International (Firm))

Ivan Shishkin / Victoria Charles [editor] and Irina Shuvalova.

pages cm

Victoria Charles, editor. Irina Shuvalova and Peter Leek, authors. Related to Ivan Shishkin and Russian painting--Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Shishkin, Ivan Ivanovich, 1832-1898. I. Shuvalova, Irina Nikolaevna. Ivan Shishkin. II. Leek, Peter. Russian painting. Selections. III. Title.

N6999.S53A4 2013

759.7--dc23

2013033091

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-253-2

Victoria Charles and Irina Shuvalova

Ivan Shishkin

Content

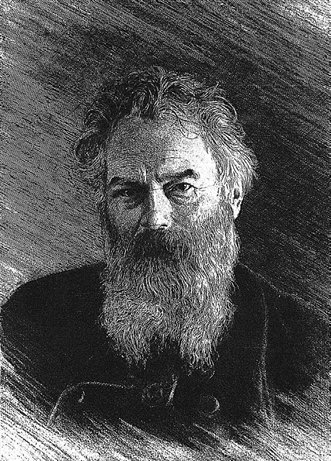

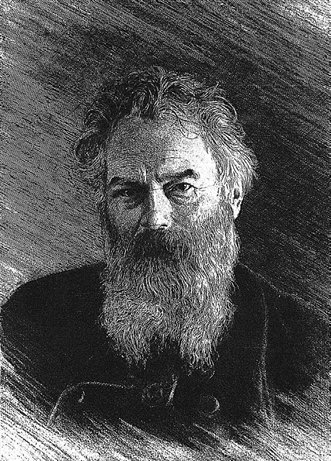

Self-Portrait, 1886.

Etching, 24 x cm .

The State Hermitage Museum,

St Petersburg.

Ivan Shishkin

and

Russian Landscape Painting

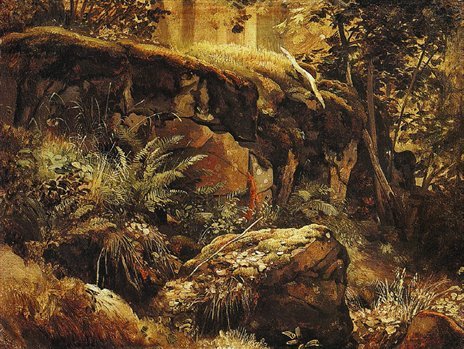

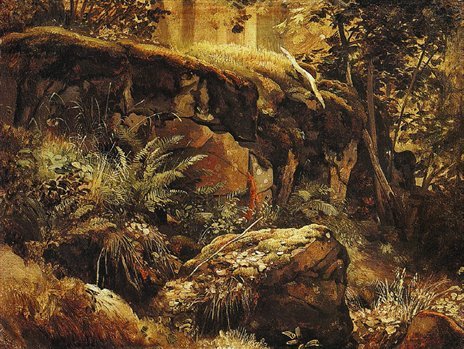

Boulders in a Forest. Valaam (study), c. 1858.

Oil on canvas, 32 x cm .

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

From the 18 th Century to the 1860s

It was only in the last quarter of the 18 th century and during the first part of the 19 th century that landscape painting in Russia emerged as a separate genre. Artists such as Fyodor Alexeyev (1753-1824), Fyodor Matveyev (1758-1826), Maxim Vorobiev (1787-1855), and Sylvester Shchedrin (1791-1830) produced masterpieces of landscape painting, although their work was heavily influenced by the Latin tradition by painters such as Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin, and Canaletto it is in the work of Venetsianov and his followers (for example, in his Summer: Harvest Time and Spring: Ploughing) that landscape with a truly Russian character makes its first appearance.

Two of Venetsianovs most promising pupils were Nikifor Krylov (1802-1831) and Grigory Soroka (1823-1864). Despite the brief span of their working lives, both of these artists were to have a considerable influence on the painters who came after them. The countryside in Kryiovs best-known picture, Winter Landscape (1827), is unmistakably Russian, as are the people that enliven it. In order to paint the scene realistically, he had a simple wooden studio erected, looking out over the snow-covered plain to the woodlands visible in the distance. Krylovs artistic career had barely begun when, at the age of twenty-nine, he succumbed to cholera. Only a small number of his works have survived.

Soroka died in even more tragic circumstances. He was one of the serfs belonging to a landowner named Miliukov whose estate, Ostrovki, was close to Venetsianovs. Conscious of Sorokas talent, Venetsianov tried to persuade Miliukov to set the young painter free, but without success. (True to his humanitarian ideals, Venetsianov pleaded for the freedom of other talented serf artists and in some cases purchased their liberty himself.) Later, in 1864, Soroka was arrested for his part in local agitation for land reforms and sentenced to be flogged. Before the punishment could be carried out, he committed suicide. One of his most representative paintings is Fishermen: View of Lake Moldino (late 1840s), which is remarkable for the way it captures the silence and stillness of the lake.

For a period of thirty or forty years most of the leading Russian landscape painters were taught by Maxim Vorobiev, who became a teacher at the Academy in 1815 and continued to teach there except for long trips abroad, including an extended stay in Italy almost up to the time of his death. Vorobiev and Sylvester Shchedrin were chiefly responsible for introducing the spirit of Romanticism into Russian landscape painting, while remaining faithful to the principles of classical art. Especially during the last decade of his life, Shchedrin favoured dramatic settings. Vorobiev went through a phase in which he was attracted by landscapes shrouded in mist or lashed by storms, and both he and Shchedrin delighted in Romantic sunsets and moonlit scenes.

View near St Petersburg , 1853.

Oil on canvas, 66.5 x cm .

The State Hermitage Museum,

St Petersburg.

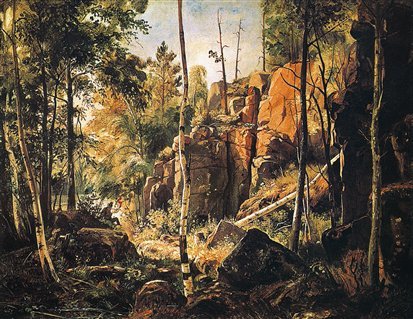

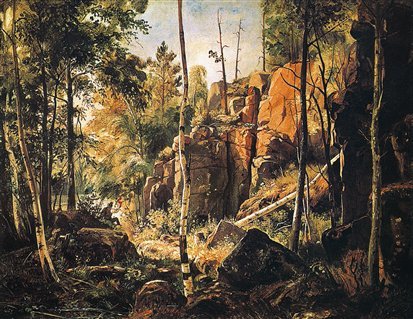

View of Valaam Island. Kukko , 1859-1860.

Oil on canvas, 69 x 87.1 cm .

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

Among Vorobievs most talented pupils were Mikhal Lebedev (1811-1837) whose landscapes are less overtly Romantic than either Vorobievs or Shchedrins and Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900), one of the most popular scenic painters of his time and certainly the most prolific. Indeed, those who reach such fame in their lifetime are rare. Barely finished with his studies, his name was already circulating throughout Russia. His learning years were situated, in effect, at a critical time. If academic rules were still in force, Romanticism was growing and each and everyone had Karl Briullovs fabulous The Last Day of Pompeii on their minds. This painting had a great effect on Aivazovskys inspiration. He was further taught by Vorobiov, whose teaching was influenced by the Romantic spirit. Aivazovsky remained faithful to this movement all his life, even though he oriented his work towards the realist genre. In October 1837, he finished his studies at the Academy and received a gold medal, synonymous with a trip to foreign countries at the cost of the Academy. But Aivazovskys gifts were such that the Council made an unusual decision: he was to spend two summers in the Crimean painting views of southern towns, present them to the Academy, and, after that, leave for Italy. The echo of the success of his Italian exhibitions was even heard in Russia. The Khoudojestvennaa Gazeta wrote

In Rome, Aivazovskys paintings presented at the art exhibition won first prize. Neapolitan Night, Chaos made such an impression in the capital of fine arts that aristocratic salons, public gatherings, and painters studios resound with the glory of the new Russian landscape artist. Newspapers dedicate laudatory lines to him and everyone says and writes that before Aivazovsky no one had shown light, water, and air with such realism and life. Pope Gregory XVI bought