Victoria Charles & Anatoli Podoksik

Pablo Picasso

(1881-1973)

Bull , 1947. Ceramic, reddish clay, 37 x 23 x 37 cm. Muse Picasso, Antibes.

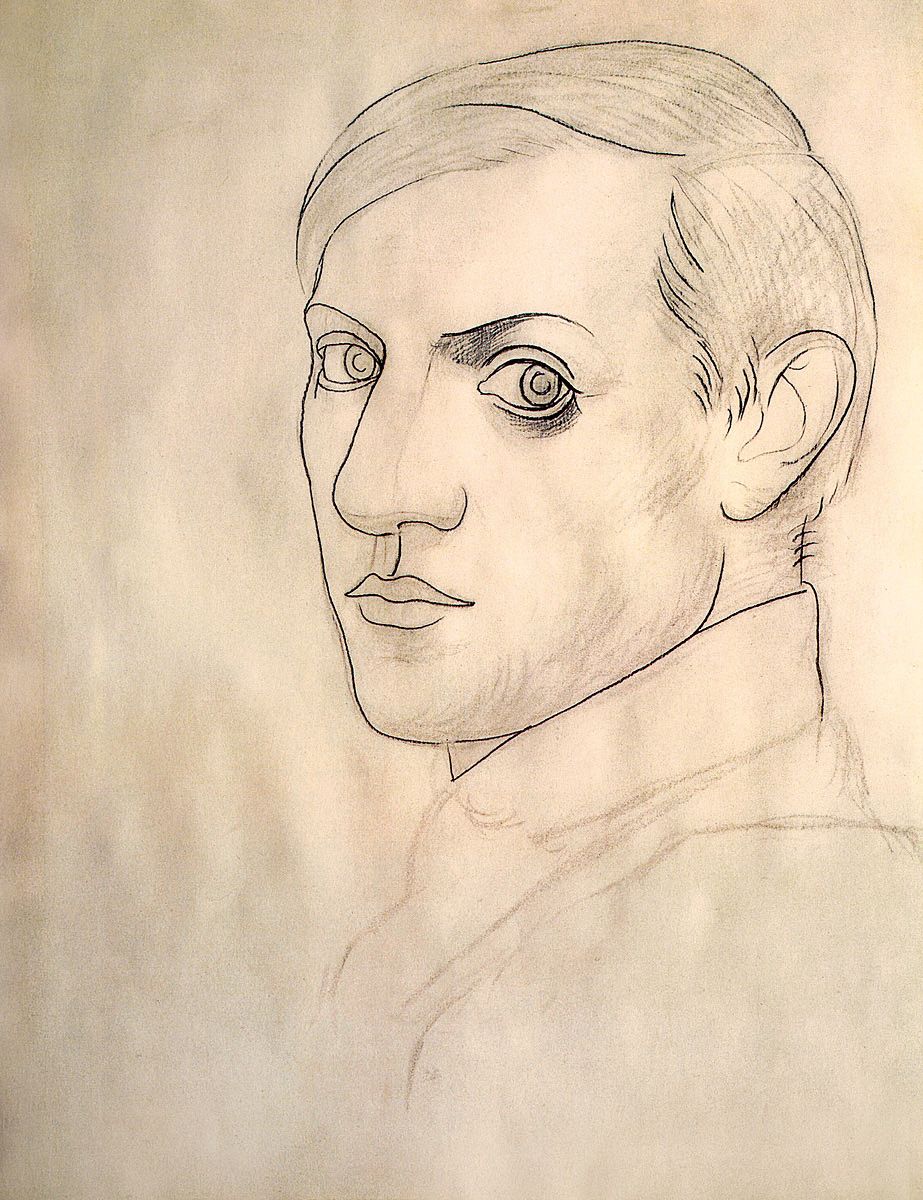

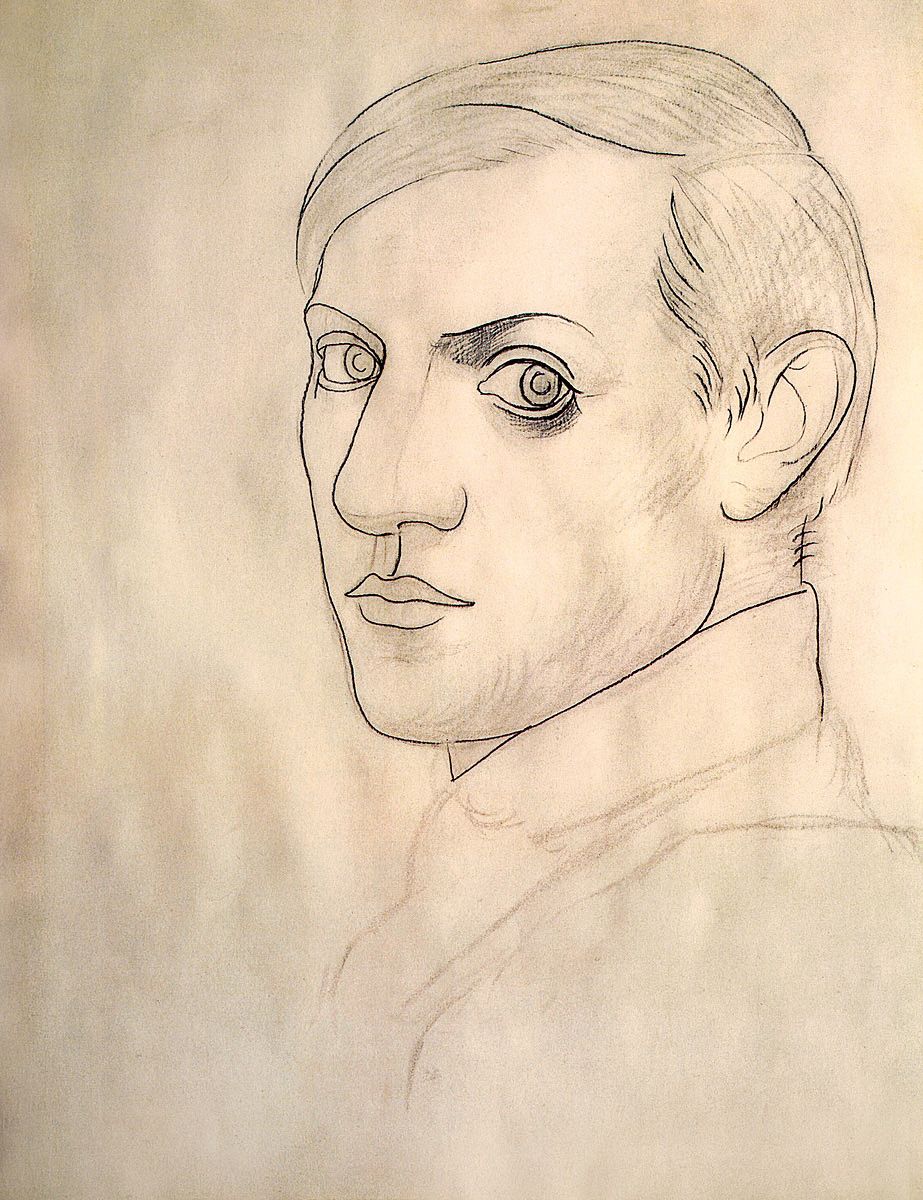

Self-Portrait , 1917-1919. Pencil and charcoal on paper, 64.2 x 49.4 cm. Muse Picasso Paris, Paris.

Author: Gerry Souter

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd.

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image Bar www.image-bar.com

Banco de Mxico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo n2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtmoc 06059, Mxico, D.F.

Estate of Pablo Picasso, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Man Ray Trust / Adagp, Paris

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78525-705-6

Contents

Portrait of the Artists Mother , 1896. Pastel on paper, 49.8 x 39 cm. Museu Picasso, Barcelona.

Beginnings

Although, as Picasso himself put it, he led the life of a painter from very early childhood, and although he expressed himself through the plastic arts for eighty uninterrupted years, the essence of Picassos creative genius differs from that usually associated with the notion of the artiste-peintre. It might be more correct to consider him an artist-poet because his lyricism, his psyche, unfettered by mundane reality, and his gift for the metaphoric transformation of reality are no less inherent in his visual art than they are in the mental imagery of a poet.

According to Pierre Daix, Picasso always considered himself a poet who was more prone to express himself through drawings, paintings, and sculptures.

Picasso had a craving for poetry and attracted poets like a magnet. When they first met, Guillaume Apollinaire was struck by the young Spaniards unerring ability to straddle the lexical barrier and grasp the fine points of recited poetry. One may say without fear of exaggeration that whilst Picassos close friendship with the poets Jacob, Apollinaire, Salmon, Cocteau, Reverdy, and luard left an imprint on each of the major periods of his work, it is no less true that his own innovative work had a strong influence on French (and not only French) 20 th -century poetry.

Jos Ruiz Blasco, Pablo Picassos father.

Maria Picasso Lopez, Pablo Picassos mother.

And this assessment of Picassos art, so visual and obvious, yet at times so blinding, opaque, and mysterious, as that of a poet, is dictated by the artists own view of his work. Picasso once said: After all, the arts are all the same; you can write a picture in words just as you can paint sensations in a poem.

Picasso, however, was born a Spaniard and, so they say, began to draw before he could speak. As an infant he was instinctively attracted to the artists tools. In early childhood he could spend hours in happy concentration drawing spirals with a sense and meaning known only to himself; or, shunning childrens games, he would trace his first pictures in the sand. This early self-expression held out promise of a rare gift.

The first phase of life, preverbal, preconscious, knows neither dates nor facts. It is a dream-like state dominated by the bodys rhythms and external sensations. The rhythms of the heart and lungs, the caresses of warm hands, the rocking of the cradle, the intonation of voices, that is what it consists of. Now the memory awakens, and two black eyes follow the movements of things in space, master desired objects, express emotions.

Sight, that great gift, begins to discern objects, imbues ever-new-shapes, captures ever-broader horizons. Millions of as-yet-meaningless visual images enter the infantile world of internal sight where they strike immanent powers of intuition, ancient voices, and strange caprices of instinct. The shock of purely sensual (visual-plastic) impressions is especially strong in the South, where the raging power of light sometimes blinds, sometimes etches each form with infinite clarity.

And the still-mute, inexperienced perception of a child born in these parts responds to this shock with a certain inexplicable melancholy, an irrational sort of nostalgia for form. Such is the lyricism of the Iberian Mediterranean, a land of naked truths, of a dramatic search for life for lifes sake, in the words of Garcia Lorca, one who knew these sensations well. Not a shade of the Romantic here: there is no room for sentimentality amid the sharp, exact contours and there exists only one physical world. Like all Spanish artists, I am a realist, Picasso would say later.

Gradually the child acquires words, fragments of speech, building blocks of language. Words are abstractions, creations of consciousness made to reflect the external world and express the internal. Words are the subjects of imagination, which endows them with images, reasons, meanings, and conveys to them a measure of infinity. Words are the instrument of learning and the instrument of poetry. They create the second, purely human reality of mental abstractions.

In time, after having become friends with poets, Picasso would discover that the visual and verbal modes of expression are identical for the creative imagination. It was then that he began to introduce elements of poetic technique into his work: forms with multiple meanings, metaphors of shape and colour, quotations, rhymes, plays on words, paradoxes, and other tropes that allow the mental world to be made visible. Picassos visual poetry attained total fulfilment and concrete freedom by the mid-1940s in a series of paintings of nudes, portraits, and interiors executed with singing and aromatic colours; these qualities are also evident in a multitude of Indian ink drawings traced as if by gusts of wind.

We are not executors; we live our work. That is the way in which Picasso expressed how much his work was intertwined with his life; he also used the word diary with reference to his work. D.H. Kahnweiler, who knew Picasso for over sixty-five years, wrote: It is true that I have described his uvre as fanatically autobiographical.

That is the same as saying that he depended only on himself, on his Erlebnis. He was always free, owing nothing to anyone but himself. Jaime Sabarts, who knew Picasso most of his life, also stressed his complete independence from external conditions and situations. Indeed, everything convincingly shows that if Picasso depended on anything at all in his art, it was the constant need to express his inner state with the utmost fullness.