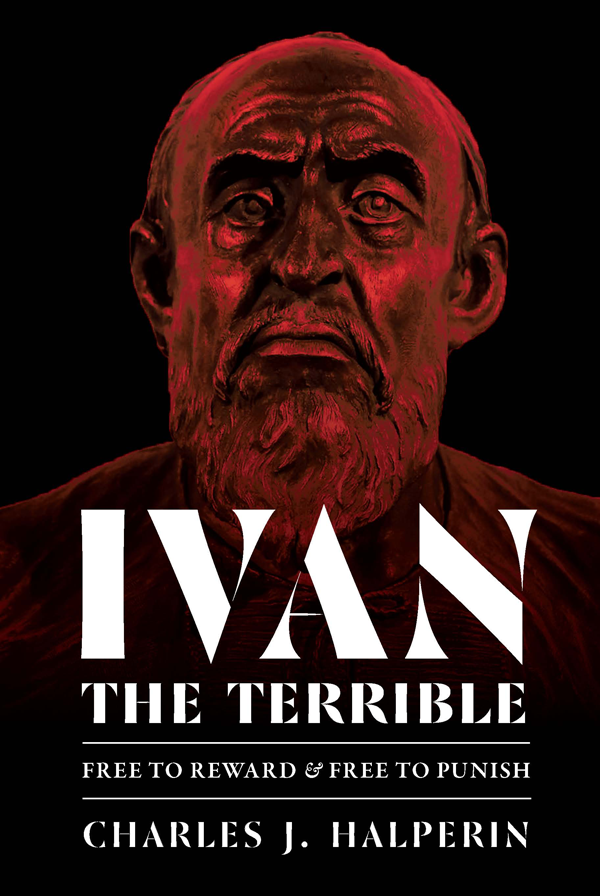

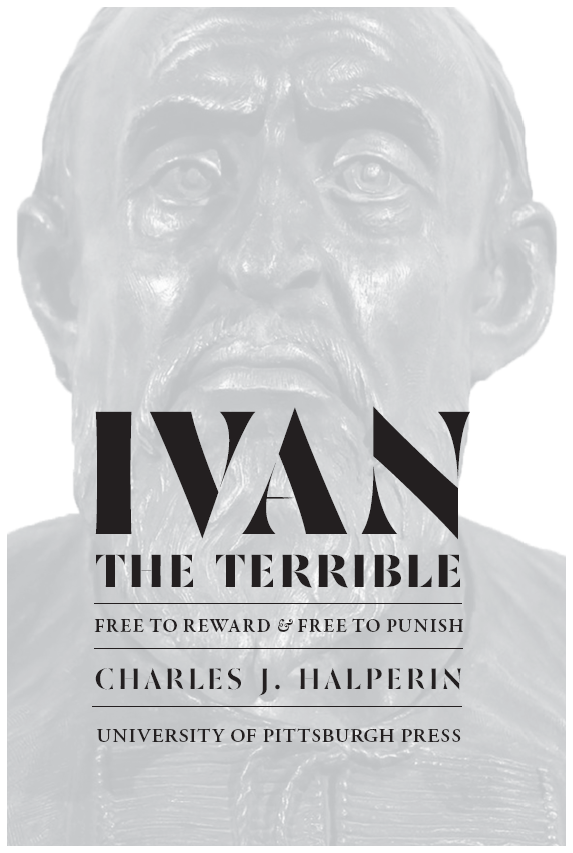

COVER ART: Mikhail Gerasimovs forensic facial reconstruction and bust of Ivan the Terrible, 1953.

COVER DESIGN: Alex Wolfe

Preface & Acknowledgments

This book could not have been written without the assistance of the Slavic Reference Service, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library, and Inter-Library Loan, Document Delivery Service, Herman B Wells Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

I wish to thank all of my colleagues who have listened to, commented on, or responded to my convention and conference papers on Ivan IV, and endured endless conversations with me on the subject; Maria Arel, Daniel Kaiser, and Russell Martin, for copies of unpublished conference papers or essays and permission to cite them; Isaiah Gruber, for a copy of an inaccessible article; the referees of all my articles on Ivan IV; the late Norman Ingham and Ann Kleimola, for inviting me to do presentations at the Midwest Medieval Slavic Workshop at the University of Chicago and the Early Russian History Workshop at the Summer Research Laboratory of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, respectively; Donald Ostrowski, for invitations to address the Harvard Early Slavists Seminar; Jennifer Spock and Barbara Skinner, for arranging campus visits to Eastern Kentucky University and Indiana State University, respectively; and Dr. Predrag Matejic, for an invitation to deliver the Second Annual Hilandar Public Lecture, sponsored by the Hilandar Research Library and the Resource Center for Medieval Slavic Studies at The Ohio State University. I also wish to express my gratitude to the Gang of Four and all of my thirteen benefactors for their generosity in a project unrelated to Ivan the Terrible.

Barbara Skinner and Robert O. Crummey read earlier drafts of this book. I cannot thank them enough for their assistance. I also wish to thank Peter Kracht, director of the University of Pittsburgh Press, Professor Jonathan Harris, editor of its Russian and East European Studies series, and the two anonymous readers for the University of Pittsburgh Press. All remaining errors are my responsibility alone.

I use the Library of Congress system for transliterating Russian. Russianwords appear in the text without diacritical marks at the end of words, except for Rus, which refers to the medieval East Slavs.

Muscovy utilized the Byzantine calendar from the Creation of the World, circa 5508 BCE, in which the year began on September 1. When we know the Byzantine year of an event but not the month, it is impossible to be certain of the CE calendar year, because September to December were one year earlier than January through August. In such cases the convention is to put a slash between the years: 1555/1556 means in either 1555 or 1556, depending upon the month; 15551556, with a dash, means from 1555 to 1556.

The field of Ivan the Terrible studies has flourished in recent years, and some sources have been issued in new editions. I have cited only the edition I have used.

In the sixteenth century foreigners called the country Ivan ruled Muscovy and its inhabitants Muscovites. Ivans subjects referred to themselves as Russian or Rus, the same term used by the East Slavs as early as the tenth century. I find the modern connotations of the word Russia misleading in reference to sixteenth-century history, so I prefer to use Muscovy instead.

For reasons of space, it is impossible for me to cite, let alone engage, all of the scholarly works I have consulted. For the same reason, I cannot point out all factual errors in those works.

Introduction

On August 12, 1976, a situation comedy about an irascible paterfamilias and his household of colorful denizens debuted as a summer replacement on the CBS television network. It was not very funny and went off the air just a month later. The series was set in Moscow, its protagonist was named Ivan, and it was called Ivan the Terrible. Ivans celebrity status explains how inmates of a Nazi concentration camp could label a sadistic Ukrainian guard named Ivan Ivan the Terrible and how American media could dub a 2004 hurricane named Ivan Ivan the Terrible.

Ivans evil reputation precedes him, prejudices scholarship, and distorts history. Russians writing about Ivan have to contend with the sheer weight

During his lifetime Ivan was both idealized and demonized. Domestic sources extolled him as the God-chosen, pious tsar. This positive image of Ivan infused literary texts such as the Book of Degrees of Imperial Genealogy, a thematic history of Ivans dynasty from Kievan times (starting in the ninth century and ending in the middle of the thirteenth century) to 1563, and artistic works such as the icon Blessed Is the Host of the Heavenly Tsar (often called the Church Militant), which most scholars believe depicts Ivans conquest of the Tatar khanate of Kazan, and works created under the supervision of state or church authorities. One contemporary Muscovite, boyar Prince Andrei Kurbskii, produced perhaps the most influential negative image of Ivan, but only from the safety of exile in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Kurbskii wrote several letters and a History of the Grand Prince of Moscow denouncing Ivan. The satanic image of Ivan propagated by such publications created the still pervasive negative myth of Ivan.

This foreign satanic image was largely borrowed. Foreigners lifted images of Ivans tyranny verbatim from texts about other monstrous rulers from antiquity on. Many authors appropriated stories from literature about the Ottomans, which demonized the Ottoman sultan.

Contemporary foreign writings also presented Ivan as a typical Muscovite barbarian. Ethnic origin was used to explain the Eastern tyranny of Ivan and the Ottomon sultan but not the Western tyranny of civilized Romans such as Nero or Caligula. Ivan became the personification of what modern scholars call Russian exceptionalism, the theory that Russias history differed significantly from that of Europe, for the worse. Ivan was uniquely worse than any non-Russian ruler, because Russians were uniquely worse than any other people. Such stereotyping must be rejected. Other sixteenth-century monarchs also took a cavalier attitude toward the lives of their subjects. If Ivan was no worse than his contemporaries, neither was he any better. He resembled his contemporaries among foreign rulers more than he did his Muscovite predecessors or successors.