ibidem-Press, Stuttgart

Contents

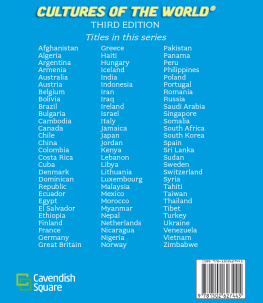

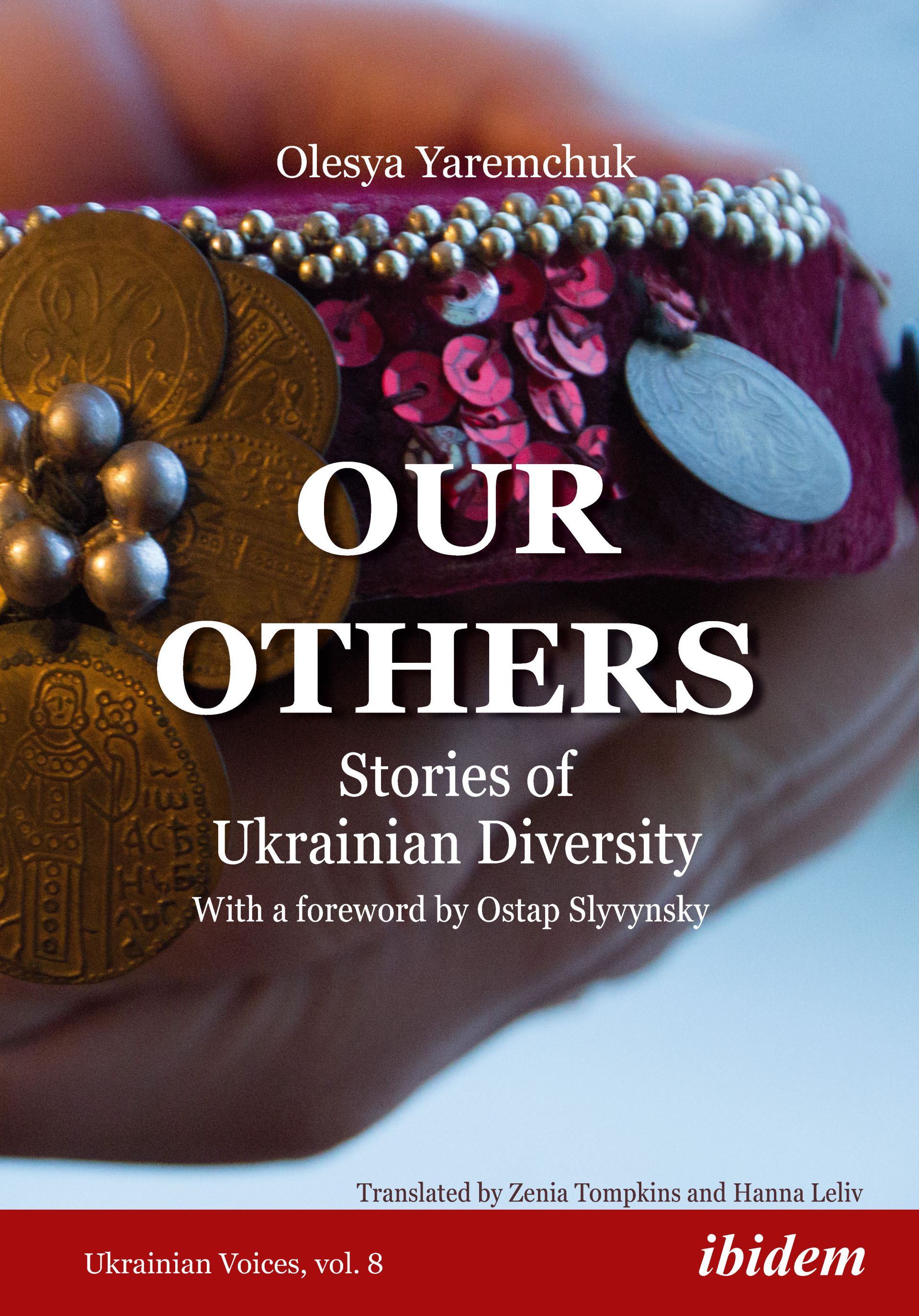

Hrushvytsia Persha, Czechs and Slovaks

Vasiukivka, Meskhetian Turks

Zmiivka, Swedes

Hertza, Romanians

Mali Selmentsi, Hungarians

Toretsk, Roma

Brody, Jews

Velykyi Bereznyi, Liptaks

Vynohradivka, Gagauzes

Pavshyno, Germans

Obava, Vlachs

Dovbysh, Poles

Novooleksiyivka, Crimean Tatars

Kuty, Armenians

FOREWORD

The Polish-British sociologist Zygmunt Bauman writes in his Postmodernity and Its Discontents, There are, however, things for which the right place has not been reserved in any fragment of man-made order. They are out of place everywhere.

An ill-chosen birthday gift, a picture left on the wall by previous tenantstheres no using such things, but theres no throwing them away either. Theyre jarring; they dont match the decor; they belong to some other aesthetic that we dont want to have anything to do with. The simplest thing would be to stash them in a dark corner and forget about them, and thats what we typically do.

But what if this happens with people? A new landlord enters the room of society with his designers, who are carrying skillfully drafted blueprints for a new world scheme. Order reigns on these pages. Everything is modern and utilitarian and formulated in accordance with a unified conceptualization. There are no old framed photographs: Faces from the past arent needed here. Who are these people? Where did they come from? What language do they speak? It doesnt matter. If they reject their preassigned roles on the stage of the new society, they belong in the closet or even the trash bin. A yearning for definitive solutions has been a fundamental trait of modern human resource managers. Thats what these people are called nowadays, no?

One of the journeys described in this book leads us to the village of Dovbysh in the Zhytomyr Oblast, where a small Polish community lives, mostly descendants of the returnees who managed to survive in Stalin-era settlements in Kazakhstan. These people, who live here in Ukraine on account of the survivors, gather every Sunday at a Polish Roman Catholic church to celebrate mass together and then once more dissolve among the Soviet buildings [that] obscure everything with their awkward bulk.

Such is our Ukraine, this middle land through which waves of both voluntary and forced migrations rolled for centuries, leaving behind little islands of diverse cultural communities. Then eventually, in the twentieth century, something else rolled through: a steamroller of planned homogenization of language, culture, religion (or rather, its absence), domesticity, and worldview (because what else is there to call it?). This is what this Ukraine of ours looks like today; this is its scale model, so to speak: a gray hodge-podge of typical Soviet construction amid which only the most attentive eye will discern something other, left intact in this new and ordered landscape either by someones negligence or willful stubbornness. A small Polish Catholic church where the congregation sings in another language; a traditional dish that has been prepared for ages in a few or a few dozen houses in the neighborhood, possibly the only memento of a long journey from snow-capped mountains once undertaken by ancestors; a craft brought over from a faraway land; a handful of words in another language heard in childhood that neighbors dont understand.

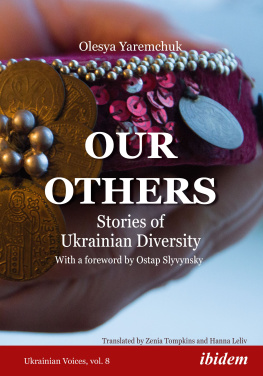

Yes, these islands are small, at times so tiny that you wouldnt spot them without a jewelers loupe: like a gem inlay on a more or less smooth surface that, fascinating as it is, is made infinitely richer by these little crystals of otherness. This book is precisely such a magnifying glassa moving, accurate, and love-filled lens that reveals places where what is Ukrainian suddenly expands, opens up to all four corners of the world, and overcomes the absurd boundaries of ethnic nationalism as naturally as a fish crosses different countries territorial waters.

It is indisputably a sign of ones wisdom and maturity to be able to say: our Armenians and Jews; our Poles, Czechs, and Slovaks; our Roma; our Germans; our Gagauzes; our Vlachs and Albanians. Only then, and not sooner, will they all stop being homeless. Yes, theyre homeless, and its our fault, the fault of the so-called social majoritybecause so long as they remain foreigners, they will be denied a place: A foreigner is one who is denied a place in space, who always belongs more comfortably elsewhere. These peoplethe ones who have borne the brunt of Stalins deportations and sometimes post-Soviet nationalisms as wellknow full well what this means. Theyre not surprised by it. Often, they dont expect anything from us anymore. Typically, they fall silent and disappear. They move away, they assimilate once and for all, they die.

Im afraid.

Of whom?

Of everyone.

Why?

I dont know.

Will you tell me about it?

No.

This dialogue is from the story of the last Armenian woman in the Carpathian village of Kuty, who remains the only living memory of a once large and vibrant community. Yes, they often kept silent. Their biographies, their ancestry and names, and their language were all often deemed criminal enough. But why are they silent still?

That is the question we need to be asking ourselves time and again. There are few things in this world as dangerous as an aspiration to linguistic and cultural homogeneity, and there are few things as sad as an unwillingness to unwind this process and examine what survived under the steamroller of history: all those scattered crystals, keepsakes, and little secrets. But first and foremost, these are peopleour living compatriotsto whose existence were often completely oblivious. Lets be honest: Do we know much about our Meskhetian Turks? About our Swedes? Yet without this knowledge, any noble endeavors to build a political Ukrainian nation will be merely futile gesticulation, a shout into the void. Its impossible to invite an Other into a dialogue not knowing his or her name.

Therefore, read this book. Read it carefully.

And one more thing: You will never and in no way predict at precisely which moment and by which criteria you yourself (or I, or anyone else) may be branded a foreigner who threatens the order, the purity of the landscape, or the vision of some or another designer. Hence, all of us are Others held together by only understanding, empathy, and love. This book is about this too. In fact, its about this first and foremost.

Ostap Slyvynsky

Sergiy Polezhaka

APPLES FROM A FORGOTTEN GARDEN

It was like this: When the Czech boys were taken off to the war, they enlisted in General Ludvik Svobodas army corps, Yosyp Mykhalchyn, from the village of Hrushvytsia Persha just outside Rivne, explains loudly and expressively. The Czechs saw right away what a collective farm meant and what real Soviets were all about. And one of the Czechs told the commander, We want to leave the Volyn colonies and go back to our country. Well liberate Prague, just let us go back.

The Prague Offensive, which ended on May 11, 1945, became the Red Armys final offensive operation in Europe during World War II. During the operation the Soviets took over 850,000 German soldiers and officers captive, as well as thirty-five generals. The Volyn Czechs too participated actively in the liberation of Prague. General Svoboda had no choice but to honor his promise and allow the colonists to return home.