Contents

Guide

A BOUT THE A UTHOR

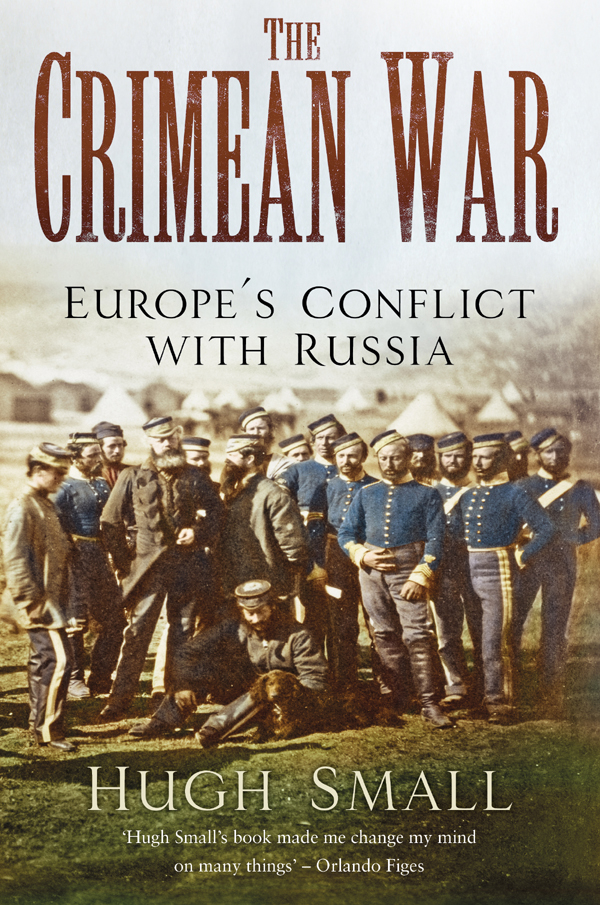

Hugh Small is the author of A Brief History of Florence Nightingale, and her Real Legacy, a Revolution in Public Health. He is an acknowledged expert on the war in the Crimea and has appeared on Channel 4 News, BBC2, Sky News and contributed to History Today on the subject. He lives in Central London.

Additional Crimean War material can be found on the authors website.

www.hugh-small.co.uk

Cover illustrations: Front: Col Doherty and men of the 13th Light Dragoons. (Library of Congress) Back: 3D reconstruction of a view of the Crimean peninsula looking west. (Author)

First published in 2007 titled The Crimean War: Queen Victorias War with the Russian Tsars

This edition first published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Hugh Small, 2007, 2018

The right of Hugh Small to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8742 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Index

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor of the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research for permission to use material from my article in the autumn 2005 issue on The 1855 Allied Campaign Plan. I acknowledge the permission of the Director of the National Army Museum to quote from Lord Raglans papers, and am grateful to the staff there and at the Newcastle Collection at Nottingham University, the National Archives of Scotland, the Queens Lancashire Regiment Museum at Preston, the British Library, The National Archives and many regional record offices. In the context of the last I would also like to thank those who have worked behind the scenes to make it possible to consult an ever increasing number of archive catalogues online.

I have benefited from the research of members of the Crimean War Research Society, and from discussions with many of them, including Keith Smith who kindly allowed me to include some of his photographs. The quotation from Mark Adkins The Charge is by permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd. I would also like to acknowledge the important role played in my research by the London Library.

1

Truth: The First Casualty of War

The truth about sensible Victorian Britains invasion of Russia in the winter of 1854 has never been published. This is because a deliberate deception was mounted during and after the Crimean War to disguise Britains failures, and historians have been deceived ever since. The original purpose of the deception was to downplay the importance of the war by blaming its outbreak on mistakes by discredited politicians and to reassure Victorian public opinion that Britain had not suffered from the indecisive outcome. Historians today still rely on versions of official documents which were altered to disguise the reasons why Britain invaded the Crimea, and retell a fairy tale (in the phrase of William Howard Russell, who was present) pretending to describe events on the battlefield. The British Government suppressed inconvenient official studies of what went wrong in Florence Nightingales hospital. Both French and British Governments kept secret a mutiny of the British generals, which caused their joint siege of Sebastopol to continue after its futility became obvious and then made Britains exasperated ally withdraw from the struggle. Official documents containing the truth on all this and more have lain unexamined since they were released fifty years after the war. There has been little interest in the Crimean War from academic historians; they may have been put off by the early portrayal of the war as a historically irrelevant mistake.

It is understandable that British historians close to the events should misrepresent a war in which their side did badly. It is also understandable that their government should cooperate by withholding documents that would have revealed the truth. At the end of the war the popular mood was ugly, and there was strong feeling that heads should roll (at least figuratively) among the aristocrats who had at first mismanaged the conflict and then allowed it to end prematurely. The truth would have been inflammatory.

The British Government had tried to create a symbolic victory by ending the stalemated war with a ceremonial bang in late 1855. Using explosives, their demolition teams reduced to rubble the Russian naval dockyards and military arsenal at Sebastopol, on the shore of one of the worlds finest natural harbours. After a bloody sixteen-month siege of Russias most prized military installation, British statesmen claimed that the Russian invasion of Turkey three years earlier had been avenged and that the forthcoming Treaty of Paris would prevent Russia from ever again deploying warships in the Black Sea or from fortifying Sebastopol or any other port on its shore. They declared victory.

The peace was unpopular in Britain, where there was no victory parade as there was in France. The government tried to drum up enthusiasm for a ceremony of rejoicing, involving fireworks and illumination of public buildings, by combining it with the Queens birthday. The popular feeling remained that there was unfinished business, that we have driven the robber from the gates of Turkey but have refused to take him into custody in the words of one London newspaper. It was a peace which France insisted upon, and which the British people somewhat sulkily acquiesced in.

Unsurprisingly, the British troops idling in the Crimea in the summer of 1856, waiting for their transports home or to colonial garrisons, began to look on their French comrades with animosity. Traditional rivalry, in suspense as long as the Russians were the common enemy, now

The bitterness in Britain had a human dimension: more than 20,000 British soldiers had died in the war. One example of these individual tragedies may illustrate the loss to the country. William Poole, a twenty-year-old infantry captain from Shropshire who was shot during the final pointless attack on the Redan, was one of 400 army officers to die. Poole was the son of an artillery officer who fought at Waterloo; he was educated at Rugby and joined the 23rd Regiment the Royal Welch Fusiliers as an ensign (second lieutenant) at the age of eighteen. One year later he landed in the Crimea with his regiment and fought at the Alma and at Inkerman. During the long siege of Sebastopol he made himself unpopular with some of his comrades by complaining about the way the war was going. He moonlighted as a trader buying whole sheep and slaughtering them and selling the parts retail. This entrepreneurship was useful when the commissariat food distribution system broke down, but was also frowned on by his fellow officers. By the summer of 1855 he had tired so much of the war that he sent in his papers officially requesting to resign his commission and go home. This was his privilege, but was considered unpatriotic. On September 8th the French and British launched what proved to be their final infantry assault on Sebastopol, and carnage ensued particularly among the officers of the 23rd who tried bravely and unsuccessfully to lead their unwilling raw recruits into the Redan fortress through a hail of short-range grapeshot. Poole was out in front despite having resigned his commission and was shot through the body, the missile nearly severing his spine. He was in severe pain for several weeks a miserable existence according to his commanding officer. In the third week of September the Official Gazette arrived showing that Poole had been gazetted out of the army on 7 September the day before the battle in which he had been wounded. On 24 September Poole died, conscious and talking until the last few hours and aware that he had not needed to lead the assault because he was already a civilian.