Dedication

For my grandchildren Nina, Gavriil, and Marfa, who might live to see the twenty-second century

Russia

Dmitri Trenin

polity

Copyright Dmitri Trenin 2019

The right of Dmitri Trenin to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2019 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2770-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Trenin, Dmitri?i, author.

Title: Russia / Dmitri Trenin.

Description: Medford, MA : Polity Press, 2019. | Series: Polity histories | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018061779 (print) | LCCN 2019001303 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509527700 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509527663 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509527670 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Soviet Union--History. | Russia (Federation)--History--1991-Classification: LCC DK266 (ebook) | LCC DK266 .T655 2019 (print) | DDC 947.084--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018061779

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

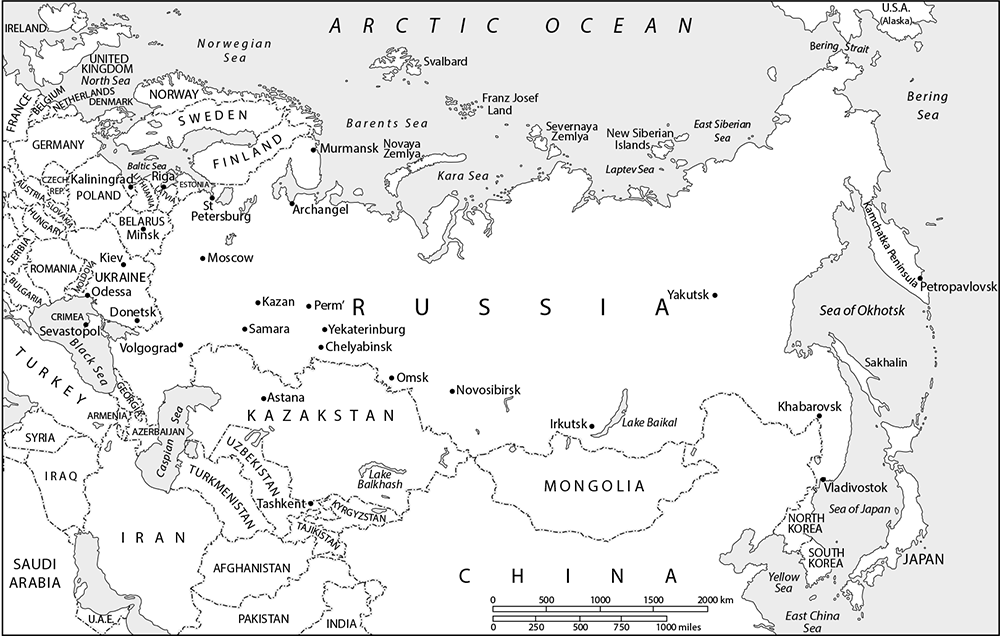

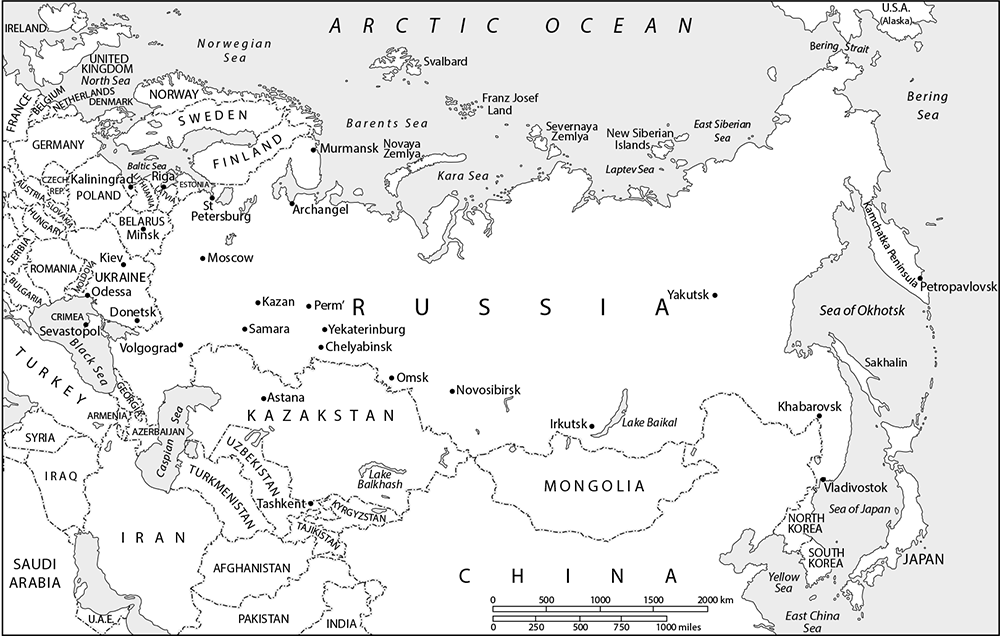

Map of Russia and Its Neighborhood

Preface

This short book is not an academic treatise. It does not pretend to reveal archival discoveries, or advance some intricate new theory of Russian history. Nor is it a textbook for students of Russia. Rather, it is an introduction to modern Russian history written for a non-Russian, non-specialist audience.

With this in mind, my purpose is simple and straightforward: to help readers understand where Russia is coming from. In other words, I will attempt to unravel the logic of the countrys history to make sense of its earlier development and its contemporary behavior, and what might be expected of it in the future.

Today Russia remains a highly politicized subject in the West. As someone who lives in Russia but is used to looking at his own country from the outside, I will offer an insiders perspective that recognizes Russias current image as mostly negative or controversial and often baffling, whilst going beyond the usual clichs to describe a Russians Russia. By this I mean the way people from ordinary men and women to prominent figures and leaders went about their daily lives, engaged in their private or collective endeavors, experienced and engaged in politics, and, occasionally, made history.

Sergiev Posad, February 11, 2019

Acknowledgments

This book was, to me, a particularly difficult undertaking. Compressing into a tight 45,000-word-long text my own countrys 120 years of history four revolutions, two world wars, a bloody domestic civil war and a cold foreign one, with several dizzying and terrifying transformations along the way, steep rises and stunning falls, followed by a comeback offering an uncertain future was a huge challenge. I naturally hesitated, but in the end was persuaded by my Polity editor, Dr. Louise Knight, to try to rise to the occasion. Louise also encouraged me, and helped me considerably to improve my original draft. I want to thank Sophie Wright for guiding me through the process of book editing. For very careful editing of the text, I am indebted to Justin Dyer. My esteemed colleague William J. Burns, President of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC, and a former US Ambassador to Russia, has read the manuscript and commented on it, for which I am most grateful. I am also deeply thankful to my family: my wife Vera, who looked at me with understanding when I holed up in my study at weekends; my elder son Petr, a trained historian with a Moscow University degree, who read the draft most closely, and supplied numerous questions and criticisms, as well as pages of suggestions; and my younger son Andrei, who urged me never to give up.

Introduction: Russias Many Russias

The Russia of the Communist period has often been derided as a country with an unpredictable history. This is true, of course, particularly in relation to the recounting of history in official Soviet propaganda and school textbooks. There, important facts, usually from the recent past, were denied as if they had never existed, and others were grossly distorted, while all-powerful leaders, once disgraced, could end up as non-persons overnight all to suit the current demands of the new party leadership. My parents-in-law kept a complete set of the second edition of the Grand Soviet Encyclopaedia. One day, I found inserted in volume 2, which was published in 1950, several loose pages with a note sent by the publisher (sometime in 1953 or shortly thereafter). The note asked the owners of the volume to tear out the pages containing the biography of Stalins secret police chief Lavrentiy Beria and replace them with the readily supplied new pages, which contained no entry on him. Touchingly, the note even instructed the book owners how to do this carefully without damaging the book. My in-laws never did what they had been asked to do, but they kept the note and the extra pages in the book next to the portrait of the disgraced Stalinist monster as a relic of one of the zigzags of Soviet history.

Russia is hardly unique in letting its leaders play with history to legitimize their rule, to claim a special status in world affairs, or to indicate a future trajectory. Today, history politics is on rich display in a number of countries, from post-Communist Eastern Europe to post-Soviet Ukraine, the Caucasus, and Central Asia: all nation-building is essentially an exercise in myth-making. In Russia, the job, as it turns out, is never complete, as a function of the constant search for the right vector of development. A fresh attempt at this is under way even as you read these lines. Dont get me wrong: serious historical research has always existed in Russia. Here, I discuss history politics as the use of the past to legitimize the present and chart ones way into the future.

This is not merely an exercise in political expediency. Russia stands out as a country that has had to constantly reinvent itself. Whenever an existential crisis arrived, Russia virtually turned against its own past, creating monumental discontinuities in its historical path. Thus, there are clear and seemingly unbridgeable divides between heathen and Christian Russia; the pre-Mongol Kievan (European) period and Moscows gathering of Russian lands under the Golden Hordes Asian empire; the Orthodox Muscovite tsardom and the Westernized empire of St. Petersburg; and, of course, between imperial, Soviet, and contemporary Russias. At any given moment, the countrys way forward is informed by what its leaders and the bulk of the people consider to be the true, bedrock Russia.

Next page