Also by Dominic Lieven

Russia Against Napoleon: The True Story of the Campaigns of War and Peace

Empire: The Russian Empire and Its Rivals

Nicholas II: Emperor of All the Russias

The Aristocracy in Europe, 18151914

Russias Rulers Under the Old Regime

To my teachers Leonard Schapiro and Hugh Seton-Watson

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2015 by Dominic Lieven

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

First published in Great Britain under the title Towards the Flame: Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Russia by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Random House UK

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA AVAILABLE

ISBN: 978-0-698-19556-1

Design and Map Illustrations by Daniel Lagin

Version_1

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I n writing this book, I have incurred many debts. First, I wish to extend my deep gratitude to Trinity College, Cambridge, which provided me with a very happy home while I was researching and writing this book.

Next, I would like to thank my research assistants: above all Ella Saginadze in St. Petersburg and Natalia Strunina in Moscow. Ella not only performed hugely valuable work for me in the State Historical Archive in St. Petersburg but also secured most of this books photographs. Natalia did great work on my behalf in Moscows libraries and archives but also ferried me craftily around the citys hospitals when archival work had almost killed me off. I must also thank Yuri Basilov, who did research for me in the archive of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, and Martin Albers and Jerome Greenfield, who ferreted out useful information for me in Britain.

My stay in Moscow was helped immensely by the hospitality of the Simmons family and of Vasili Kashirin: to them too great thanks. The draft chapters were read by Professors Bruce Menning and David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye. My book would have been far inferior without their advice. Bruce Menning also shared with me many of his unpublished articles and his immense knowledge of the Russian army before 1914 and its preparations for war.

I also have to thank the many archivists who made my research possible: above all the staff of the Foreign Ministry Archive in Moscow, who went far out of their way to help me, but also Professor Serge Mironenkos splendid staff at GARF, also in that city. The military archive in Moscow was the foundation for my last book and made a big contribution to this one too. Also not to be forgotten are the friendly and helpful archivists at the naval archive in St. Petersburg, the French military archive, and the British National Archives. I owe special thanks to the immensely helpful staff at the Bakhmeteff Archive of Columbia University in New York. My thanks are also due to the libraries in which I worked in London, Moscow, and Cambridge.

During my time in Moscow, I sustained a growing litany of medical problems. I would not have surmounted them and finished my research without the support of my wife, Mikiko Fujiwara.

Mrs. Elizabeth Saika and Dr. Sophie Schmitz, granddaughters of a key figure in my book, Prince Grigorii Trubetskoy, were immensely generous and helpful in sending me unpublished work about their grandfather. Sophie Schmitz kindly sent me the PhD dissertation that she herself had written about him, and Elizabeth Saika provided me with both unpublished family documents and photographs. I am very grateful to both of them.

Apart from Elizabeth Saika, the following people and institutions kindly supplied me with photographs for this book: the publishing house Liki Rossii and its director, Elizaveta Shelaeva; the Central State Archive of Cinema and Photographs in St. Petersburg; Alexis de Tiesenhausen; and the Krivoshein family. I am grateful to all of them for their help.

My publishers, Melanie Tortoroli in New York and Simon Winder in London, not only commissioned and encouraged me to write this book but also read it with great skill, providing me with extremely good advice that improved the structure and presentation considerably. At Penguin in London, I should also like to thank Richard Duguid and Marina Kemp and in particular Richard Mason, my copy editor. Very great thanks are also owed to my agent, Natasha Fairweather.

The historians who have worked around this theme and from whose ideas I have benefited are too numerous to thank individually, but special mention must be made of Professor Ronald Bobroff, who came to my rescue by providing me with a copy of a key document that I could not find in the archive. Also, Brendan Simms gave me an important work that was unavailable in bookshops.

Because this may well be the last serious book I will write on the history of imperial Russia and modern Europe, I must record my lasting gratitude to those who taught and inspired me so many years ago: In Cambridge, they included, above all, Derek Beales, Norman Stone, Simon Schama, and Jonathan Steinberg. In London, they were Leonard Schapiro and Hugh Seton-Watson. To the memory of Leonard and Hugh, fine scholars in the British empirical tradition, this book is dedicated.

NOTE

In the years covered by this book, Russians lived according to the Julian calendar. By the twentieth century, this was thirteen days behind the Gregorian calendar, by which the rest of Europe operated. To avoid confusion, throughout my text I have used the Western system. In the endnotes, when dates are recorded in the Russian calendar, I have written (OS) behind them. When one wrote from Russia to someone outside the country, it was usual to put the dates of both the Julian and the Gregorian calendars at the top of a letter, the same being true of Russians writing from abroad to anyone in Russia. I have followed this practice in my endnotes. How to transliterate Russian names that are of non-Russian origin is always a problem. I have almost always turned them back into their Latin original, except where the person in question used some different variant even when writing in Western languages. As to Christian names, I have used the Russian variant (for example, Aleksandr) for people of foreign origin when they were fully assimilated but the English version (for example, Alexander) for foreigners and subjects of the tsar who retained their non-Russian ethnic identity. As regards terminology, I have tried to steer a course that neither distorts realities nor confuses the lay reader. For example, to avoid long explanations about the shifting meanings of the terms slavophile, Slavophile, and pan-Slav, I have used the word Slavophile as a generic term to cover all those who emphasized the significance of Russias Slav identity as a guide to government policy at home and abroad.

PHOTOGRAPHS

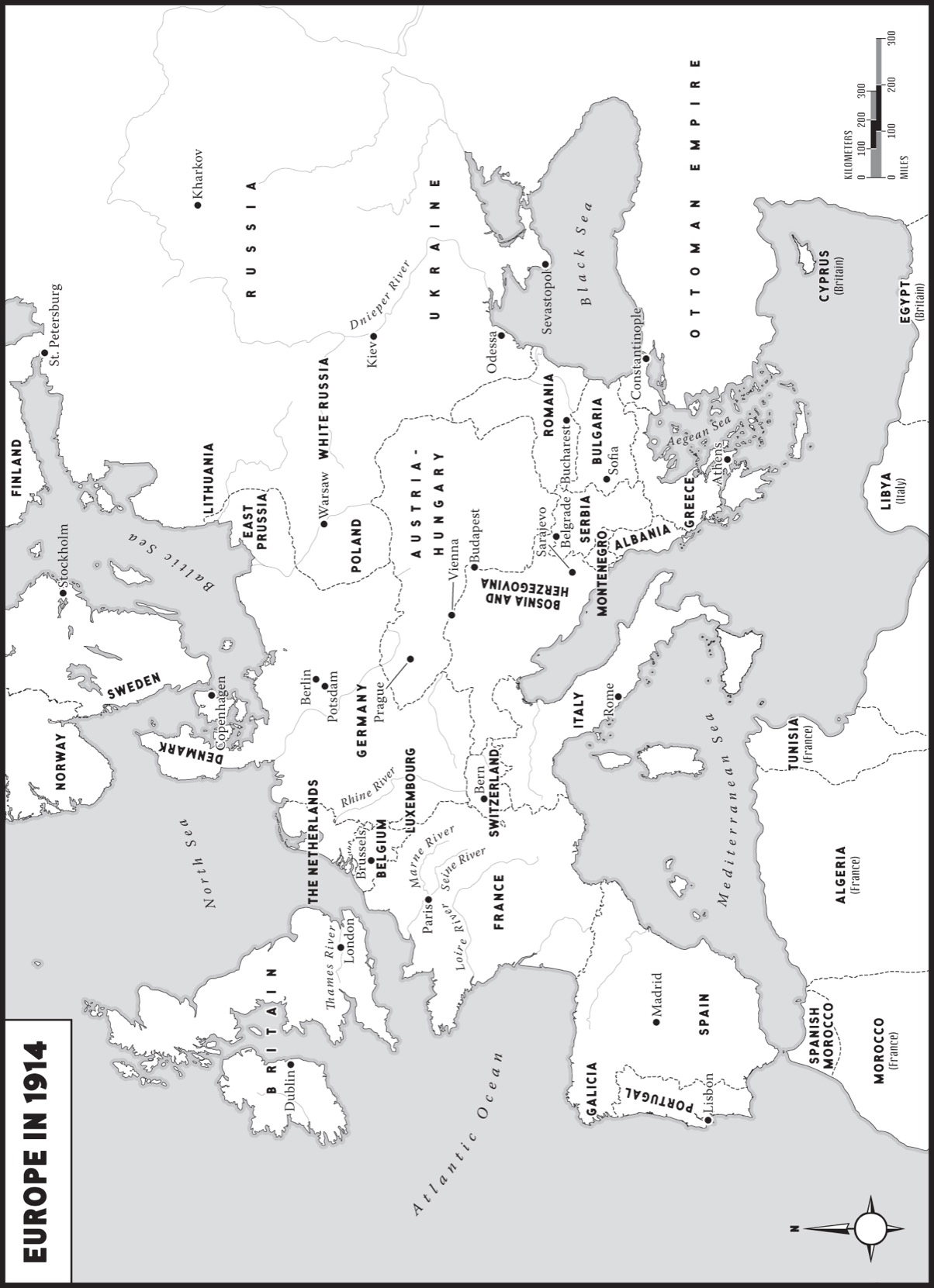

Visit http://bit.ly/TheEndofTsaristRussiaMap1 for a larger version of this map.