As the head of the Bolshevik party during the Russian Revolution, Vladimir Lenin (18701924) led the country through what were arguably its most tumultuous years. This statue of Lenin in Volgograd, Russia, stands twenty-seven meters (more than eighty-eight feet) tall.

THE RUSSIAN

REVOLUTION

S. A. Smith

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of

Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

Published by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc.

2002 by Steve Smith

Illustrated edition published in 2011 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Additional text 2011 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

Book design: Faceout Studio

Please see for image copyright information.

Printed in China

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-7900-8

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales Department at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

CONTENTS

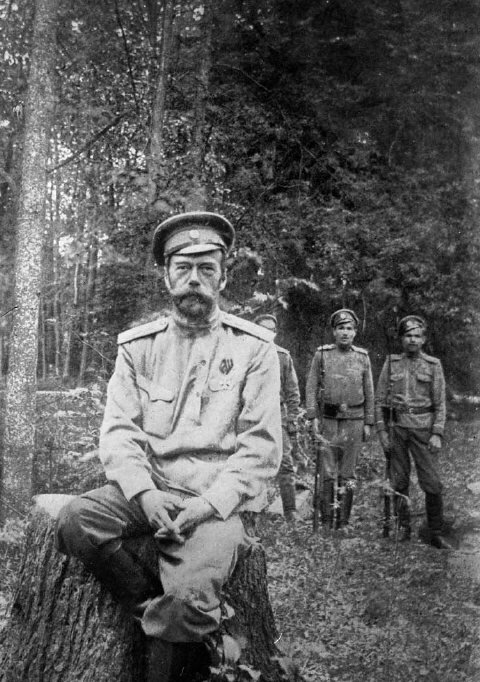

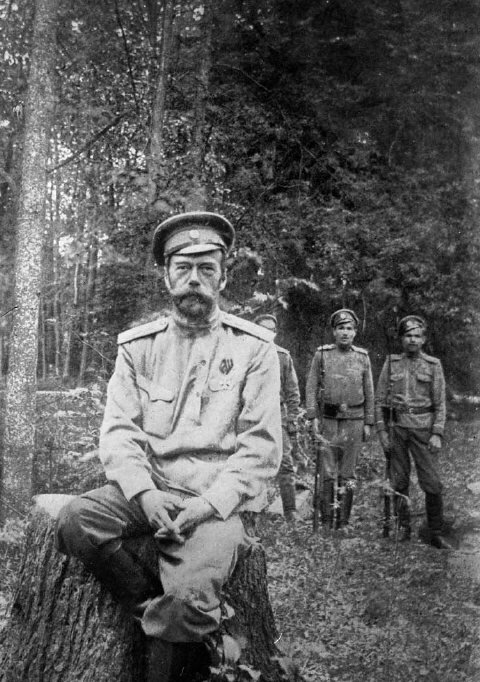

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (18681918) abdicated his throne in March of 1917 and was initially imprisoned with his family at Tsarskoye Selo, an imperial residence in what is now the town of Pushkin. This photograph of Nicholas, taken on the grounds of the residence, shows armed guards standing at the right.

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION OF 1917 saw the overthrow of the tsarist autocracy in February and the seizure of power by the Bolshevik party in October. The Bolsheviks proceeded to establish the worlds first Communist state on a territory covering one-sixth of the globe, that stretched from the Arctic to the Black Sea, from the Baltic to the Far East. Their revolution proved to be the most consequential event of the twentieth century, inspiring communist movements and revolutions across the world, notably in China, provoking a reaction in the form of fascism, and after 1945 having a profound influence on many anti-colonial movements and shaping the architecture of international relations through the Cold War. This book sets out to provide for the reader coming to the subject for the first time an analytical narrative of the main events and developments from 1917 to 1929, when I. V. Stalin launched his revolution from above, bringing crash industrialization and the forced collectivization of agriculture to the Soviet Union. It seeks to explain how and why revolution broke out in 1917; how the Bolsheviks came to power and established a regime; and how, finally, that regime evolved into a gruesome form of totalitarianism. The book attends to the ideals and aspirations that animated the contenders for power and the issues and conflicts with which they had to grapple. But it seeks to go beyond politics narrowly defined. The October Revolution set out to do nothing less than destroy an entire social system and replace it with a society superior to anything that had existed hitherto in human history. The book explores the far-reaching reverberations of that project on the economy, peasant life, work, structures of government, the family, empire, education, law and order, and the Church. More particularly, it explores what the revolution meant the hopes it inspired and the disappointments it broughtfor different groups such as peasants, workers, soldiers, non-Russian nationalities, the intelligentsia, men and women, and young people. The perspective is that of the social historian, but the central concern is political: to understand how ordinary people experienced and participated in the overthrow of one structure of domination and how they experienced and resisted the gradual emergence of a new one. Each chapter is punctuated with a couple of quotations from documents that have come to light since the fall of the Soviet Union; they are intended to give a flavor of the range of responses of those who found themselves caught up in the revolution.

In 1991 the state to which the Russian Revolution gave rise collapsed, allowing historians to see the history of the Russian Revolution in its entirety for the first time. That shift in perspective, together with the passing of the twentieth century, suggests that it is a good time to reflect more philosophically on the meaning of the revolution. Somewhat unusually for an introductory text, therefore, it touches on certain fundamental questions, such as the role of ideology and human agency in revolution, the interplay of emancipatory and enslaving elements in the Bolshevik project, and the influence of Russian culture on the development of the Soviet Union. The book incorporates advances in research and interpretation made by western scholars since the 1980sparticularly in the sphere of social and cultural historyand the work of Russian scholars who were freed from the trammels of Soviet censorship in 1991. The introductory nature of this text and the tight constraints of space preclude the standard scholarly apparatus of reference. I thus wish to apologize to and thankthe many specialists on whose work I have drawn without customary acknowledgment.

Readers should note that up to February 1, 1918, dates are given in the old style. On that date the Bolsheviks changed from the Julian calendar, which was 13 days behind that of the West, to the western calendar. The October seizure of power (October 2425, 1917) thus took place on November 67, 1917, according to the western calendar.

Warmest thanks go to Cathy Merridale and Chris Ward, who read the manuscript and offered characteristically astute and helpful comments. Needless to say, responsibility for any errors remains my own.

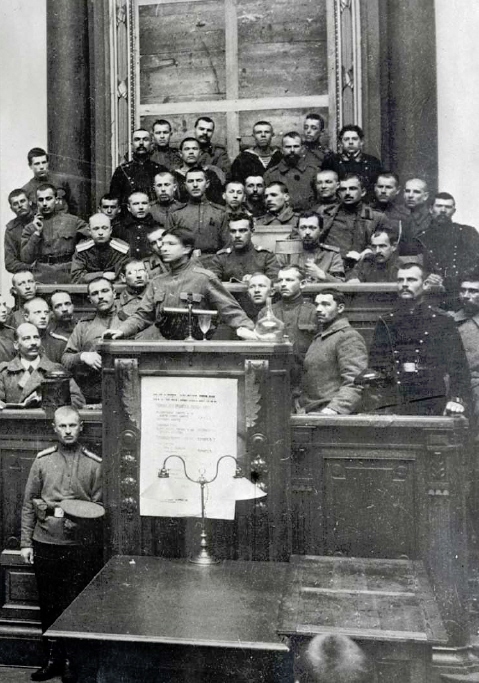

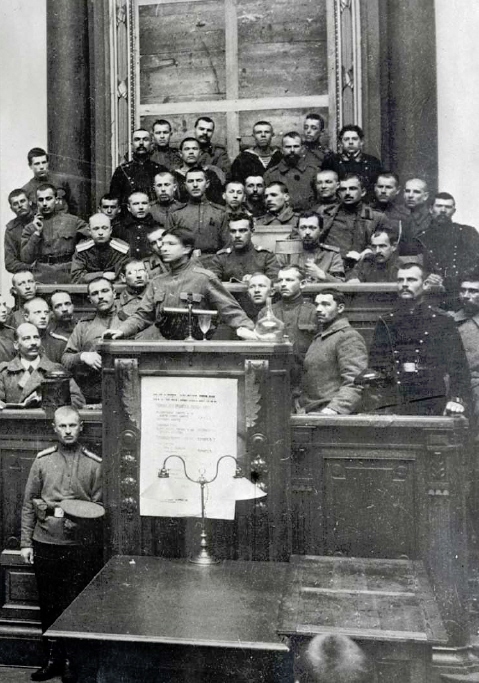

After the February revolution, workers assembled in Tauride Palace in Petrograd, the seat of the State Duma of the Russian Empire, for the purpose of forming the Petrograd Soviet. The workers are standing in front of a frame that had previously contained a picture of the tsar.

ON FEBRUARY 23, 1917, thousands of female textile workers and housewives took to the streets of Petrograd, the Russian capital, to protest about the bread shortage and to mark International Womens Day. The following day, more than 200,000 workers were on strike and demonstrators marched from the outlying districts into the city center, hurling rocks and lumps of ice at police as they went. By February 25, students and members of the middle classes had joined the protesters, who now bore placards proclaiming Down with the War and Down with the Tsarist Government. On February 26, soldiers from the garrison were ordered to fire on the crowds, killing hundreds. The next morning, the Volynskii regiment mutinied, its example quickly followed by other units. By March 1, 170,000 soldiers swarmed among the insurgents, who were by this stage attacking prisons and police stations, arresting officials, and destroying tsarist emblems of slavery. A revolution had broken out, but not until February 27 did any of the revolutionary parties manage to give leadership to it. Looking back to the revolution of 1905, the moderate wing of the Russian Social Democratic and Labor Party (RSDLP), the Mensheviks, called on workers and soldiers to elect delegates to a soviet, or council. Thus was born the Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies.

Next page