A Oneworld Paperback Original

First published in North America, Great Britain & Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014

Copyright Abraham Ascher 2014

The right of Abraham Ascher to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-387-5

eISBN 978-1-78074-388-2

Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK

Cover design by vaguely memorable

Printed and bound in Denmark by

Norhaven A/S

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

A note on dates

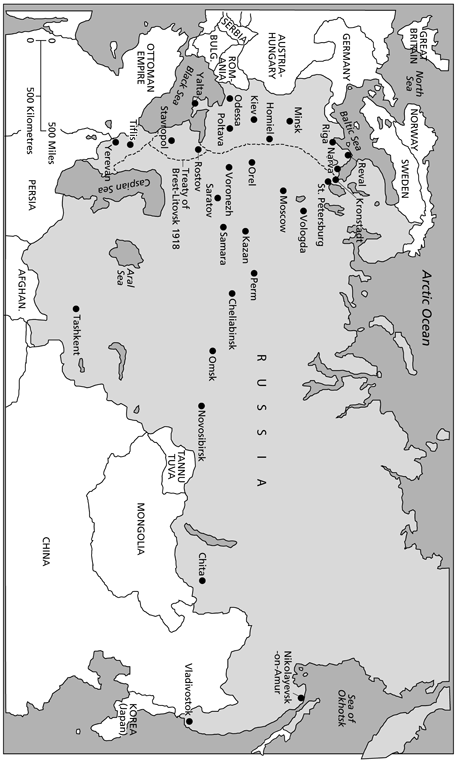

Until January 1918, Russia retained the Julian calendar, which means that the dating of events appears to be thirteen days earlier than in the Western (Gregorian) calendar in use throughout most of Europe at the time. I use the Julian calendar for all events before 1918 and the Gregorian calendar thereafter.

Contents

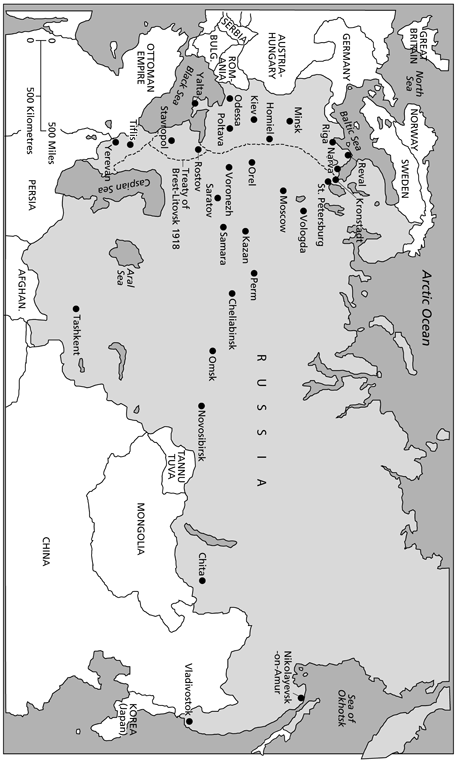

Russia, 1914

In 1919, John Reed, a young American journalist fervently committed to socialism, published a stirring eye-witness account of the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks late in October 1917. Reed had traveled to Petrograd, the capital of the Russian Empire, in September that year to report on the progress of the revolution that had erupted in February and already toppled the authoritarian tsarist regime, leaving the countrys political system in a state of uncertainty. The liberals who took control of the government were incapable of coping with the enormous problems they faced: the defeats the army was suffering at the hands of German troops in what seemed to be an endless war, the widespread industrial strikes, the peasants unauthorized seizure of land, and the growing pressure of nationality groups to secure independence. Instead of bringing about a democratic and more just society, the dethronement of the unpopular Tsar Nicholas II had led to unprecedented economic, social, and political instability that threatened to thrust the Russian Empire into chaos.

Entranced by Vladimir I. Lenin and his followers, Reed was especially interested in reporting on their role in the dramatic events that were breaking the Russian Empire apart. If the Bolsheviks came to power, he believed, they would create an egalitarian order that would soon spread to Europe and eventually to the rest of the world. Moreover, the transformation of society in Russia would not be confined to the economic and social spheres; it would also be spiritual, in the deepest sense of the word. After attending the funeral of five hundred workers who had lost their lives in the revolutionary cause, he noted that I suddenly realized that the devout Russian people no longer needed priests to pray them into heaven. On earth they were building a kingdom more bright than any heaven had to offer, and for which it was a glory to die.

Sensing the likely impact of the events he described on other countries, Reed titled his account, Ten Days That Shook the World. Lenin was so taken with the book that he unreservedly recommended it to the workers of the world, who would gain from it a clear understanding of the Proletarian Revolution and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.

Reed correctly stressed the importance of the turn of events in Russia, but he underestimated its eventual impact on world affairs. The upheaval in the Russian Empire shook the world not for ten days but for some seventy-four years. There was hardly a political development of significance in the twentieth century that was not profoundly affected by the Soviet Union, so great was the fear of Communism in many parts of the world. Had it not been for the dread of that political movement, it is highly unlikely that the Nazis would have become the largest political party in Germany and that Hitler would have been appointed Chancellor in 1933. Six years later, he plunged Europe into war and in 1941 attacked the Soviet Union, unleashing the bloodiest military conflict in human history. The Soviet Union emerged from that war as a major world power; it gained control of Eastern Europe and soon succeeded in producing nuclear weapons. Soviet leaders continued to speak of the inevitable triumph of socialism throughout the world, and they did their utmost to hasten it.

Western leaders, on the other hand, viewed that possibility as a threat to their societies and values, and spared no effort to keep Communism at bay. After World War II, when the Soviet Union emerged as a superpower, the struggle intensified and came to be known as the Cold War. That struggle between the West, led by the United States, and the Communist East dominated international relations from roughly 1948 until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. It was a war that in many ways shaped developments in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Latin America. Nothing sums up the impact of Communism on the Western world more graphically than the quip by an American professor: If you tell me what a persons view of 1917 is, I can most probably divine his political views on all major contemporary issues. Even a political analyst as perspicacious as Reed could not have foreseen that the seizure of power by a small group of radicals led by Lenin would so powerfully influence the course of history.

The road to revolution

The dream of an ideal society in Russiabegan to take shape in the 1880s, when a small group of Russian intellectuals founded a Marxist movement that claimed to represent the interests of the working class. Their leader, G. V. Plekhanov, contended that Russias development would be similar to that of Central and Western Europe. The country would be industrialized and would then undergo a bourgeois revolution that would replace the autocratic system of rule with a constitutional order dominated by the middle class, which favored capitalism. Eventually, when industrialization reached maturity and the proletariat (the industrial working class) had become a powerful force, it would stage a second, socialist revolution, which had not yet taken place in Central and Western Europe. In 1898, the Russian Marxists formed the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party, which five years later split into the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions.

Bolshevism

Bolshevism is the name of the Russian Marxist movement that emerged at the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Party held in August 1903 in Brussels and London. The party split over what appeared to be a minor difference on how to define a party member. Vladimir Lenin, in his pamphlet What Is to Be Done?, written in 1902 , had expressed his commitment to the creation of a highly centralized, elitist, and hierarchically structured political party. At the Congress, he defined a party member as anyone who recognized the partys program and supports it by material means and by personal participation in one of the partys organizations. Lenin was aiming at the formation of a cadre of professional revolutionaries. Iulii Martov, however, wished to define a party member as anyone who supported the party by regular personal association under the direction of one of the partys organizations. Martov and his followers, in other words, favored broad working-class participation in the movements affairs and in the coming revolution. It also became evident that, although both factions subscribed to a revolutionary course, the Mensheviks tended to adopt more moderate tactics than the Bolsheviks.

Next page