RUSSIA

A SHORT HISTORY

Also by Abraham Ascher

Stalin: A Beginners Guide

The Russian Revolution: A Beginners Guide

RUSSIA

A SHORT HISTORY

ABRAHAM ASCHER

CONTENTS

Writing a book is always difficult, but to write a history of Russia in about ninety thousand words, from its beginnings in the ninth century to the most recent events under President Putin, proved to be far more challenging than I ever imagined. Important events and developments that deserve several pages had often to be compressed into a few sentences, and some subjects, most notably cultural and intellectual trends, had to be accorded much less space than I would have liked. I am painfully aware that these are shortcomings of the book, but I hope that I have succeeded in my main goal, which is to present a coherent account of Russias political, social, and economic institutions as they evolved over one thousand years, so as to enable the reader to gain a better understanding of contemporary Russia.

It was in this spirit that I agreed to update the book that I had already brought up to date once before, in 2009. At that time I added a section that outlined the main features of Russian history during the first eight years of Vladimir Putins presidency. Now, it seems to me important to evaluate the changes that have occurred since the last update because this year marks a milestone in Russian history. One hundred years have passed since the tsarist regime was overthrown and the Bolsheviks under Lenins leadership took control of the country with the aim of creating a socialist economy. The means of production were to be owned by the government and there would be only minor discrepancies in income. The Bolsheviks never came close to achieving the goal of an egalitarian society, and it could be argued that since the Soviet Union was an economically backward country it would take time to achieve the final goals. But since the collapse of communism in 1991, the country has drifted further away from Lenins aims. And Russias leaders now do not even pretend to be socialists. Putin has nurtured what is generally known as a market economy heavily controlled by the state, an economy that favors the rich and that is riddled with corruption.

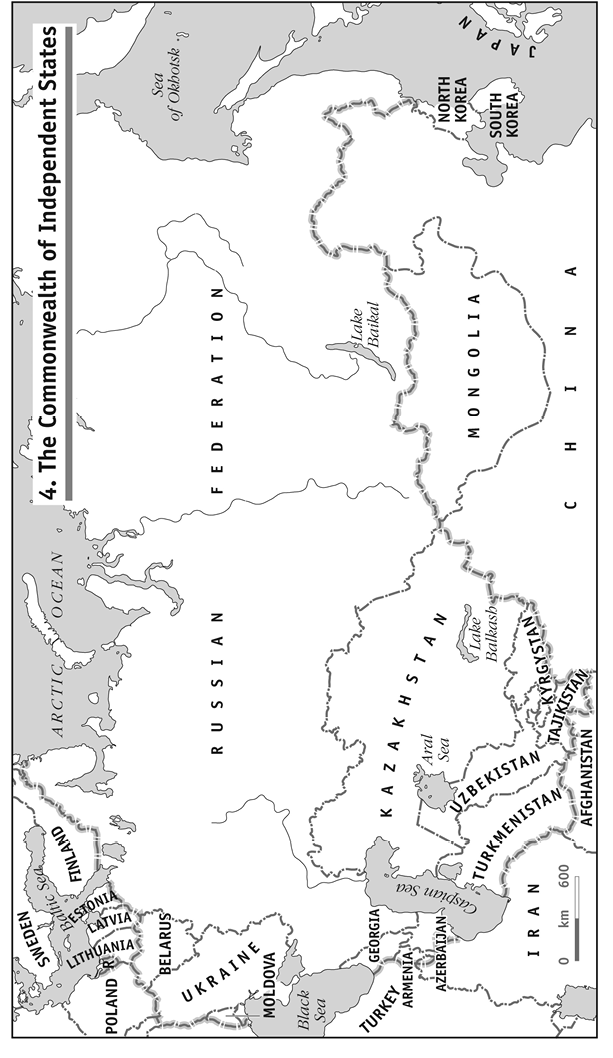

Moreover, President Putin has increasingly made the restoration of Russia as a great world power the focus of his rule. The clearest example of this is his pursuit of an aggressive policy towards Ukraine, a large state that gained independence in 1991. The Baltic countries Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania which also became independent in 1991 are now fearful that Russia may have designs on bringing them under its control. The West eyes these potential developments with much anxiety and there is a danger of continuing tension between the West and Russia. It is to be hoped that a revival of what was known as the Cold War, which lasted from 1946 until 1991, can be avoided.

There are some difficult questions that readers of this book may wish to ponder: were the revolutionaries such as Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin, who engineered the revolution of 1917, deluding themselves in believing that they could create an egalitarian society? Were there steps that these leaders or their successors could have taken to assure the realization of socialism, or at least to prevent the collapse of the Soviet Union? Does Putins increasing interest in restoring Russia as a great power suggest that nationalism is of greater concern to the citizens of Russia than the creation of a socialist society? When I began to study Russian history in the early 1950s, most historians would not have considered these questions germane or interesting. The transformation of Russia in the hundred years since the Bolsheviks assumed power in Russia makes them unavoidable.

I would not have been able to write this book had I not had the experience of teaching Russian history for more than forty years. Students in my courses have often raised difficult questions, and I am grateful to them for having stimulated me to broaden my knowledge of certain aspects of Russian history. The staff at Oneworld, Victoria Warner and Rebecca Clare, as well as the copy editor, Anthony Nanson, were most helpful at every stage of the writing of the first edition of the book. Shadi Doostdar, who supervised the preparation of the present edition, has been very supportive in my composing of the update of the 2009 edition. The anonymous reader of the manuscript made valuable comments that I took into account in revising the manuscript. David Inglesfield, the copy editor, made many suggestions that have improved this work. Finally, I would like to express my special thanks to my good friend Marc Raeff, who read the first edition of the book with his usual care and made many suggestions for its improvement. Of course, I am responsible for any errors and deficiencies that remain.

Abraham Ascher

New York, September 2017

For over a century and a half, intellectuals and scholars interested in Russia have differed sharply over the essential characteristics of the countrys economic, social, and political institutions, and its culture. Much of the time, the debate centered on the question of whether Russia was part of Western European civilization or of Asian civilization, or whether it had somehow amalgamated basic features of both. That this was not a debate taken lightly became clear as early as 1836, when the philosopher P. Ia. Chaadaev published the first of his Philosophical Letters, in which he bemoaned Russias cultural isolation and its failure to make a signal contribution to world culture. Neither of the East nor of the West, Russia, according to Chaadaev, had no great traditions of its own; alone in the world, we have given nothing to the world, we have taught it nothing... we have not contributed to the progress of the human spirit and what we have borrowed of this progress we have distorted... we have produced nothing for the common benefit of mankind. Chaadaevs sweeping and harsh pronouncements had the effect, in the words of the political thinker and activist Alexander Herzen, of a pistol shot in the dead of night. Tsar Nicholas I declared Chaadaev insane and put him under house arrest. Among Russias educated elite, Chaadaevs disparagement generated excitement of a different sort. Intellectuals took Chaadaevs views seriously and initiated a passionate debate that quickly divided them into two groups, the Slavophiles and the Westerners, and in one form or another their historical and philosophical discussions continue to this very day. An observer of contemporary conditions in Russia reported from Moscow in the Times Literary Supplement of 19 November 1999 that In Russian intellectual life, a conversation that was cut off and redirected after the Bolshevik Revolution has resumed its course. Its basic theme: East, West, whence, and whither Russia?