Executive Editor

Jenny Croghan

Commissioning Editor

Alex Stavrakas

Managing Editor

Elizabeth Castoria

Expert Editor

Gulnaz Sharafutdinova

Creative Director

Frances Baca

Art Director

Felicia Reyes

Photo Editor

Caroline Lee

Production Designer

Evelyn Whitburn

Publisher

Benjamin Wayne

ON THE COVER

The law is like a carts shaft, goes a Russian saying, it points wherever you turn it to. Bypassing constitutional technicalities, Vladimir Putin managed to secure a third non-consecutive presidential term. Seen here entering St. Andrews Hall in the Kremlin on May 7, 2012, to take his third oath of office.

Contents

BARTOSZ KOSOWSKI 2015

AUTHOR

ANASTASIA EDEL

Anastasia Edel is a Russian-American writer born during the last years of the Soviet Union. A recipient of the British Government Chevening Award, she has written a novel, Past Perfect, and numerous essays and short stories. This is her first nonfiction book. She lives with her family in California and thanks Misha Edel for his valuable consultation on this project.

VIEW POINT

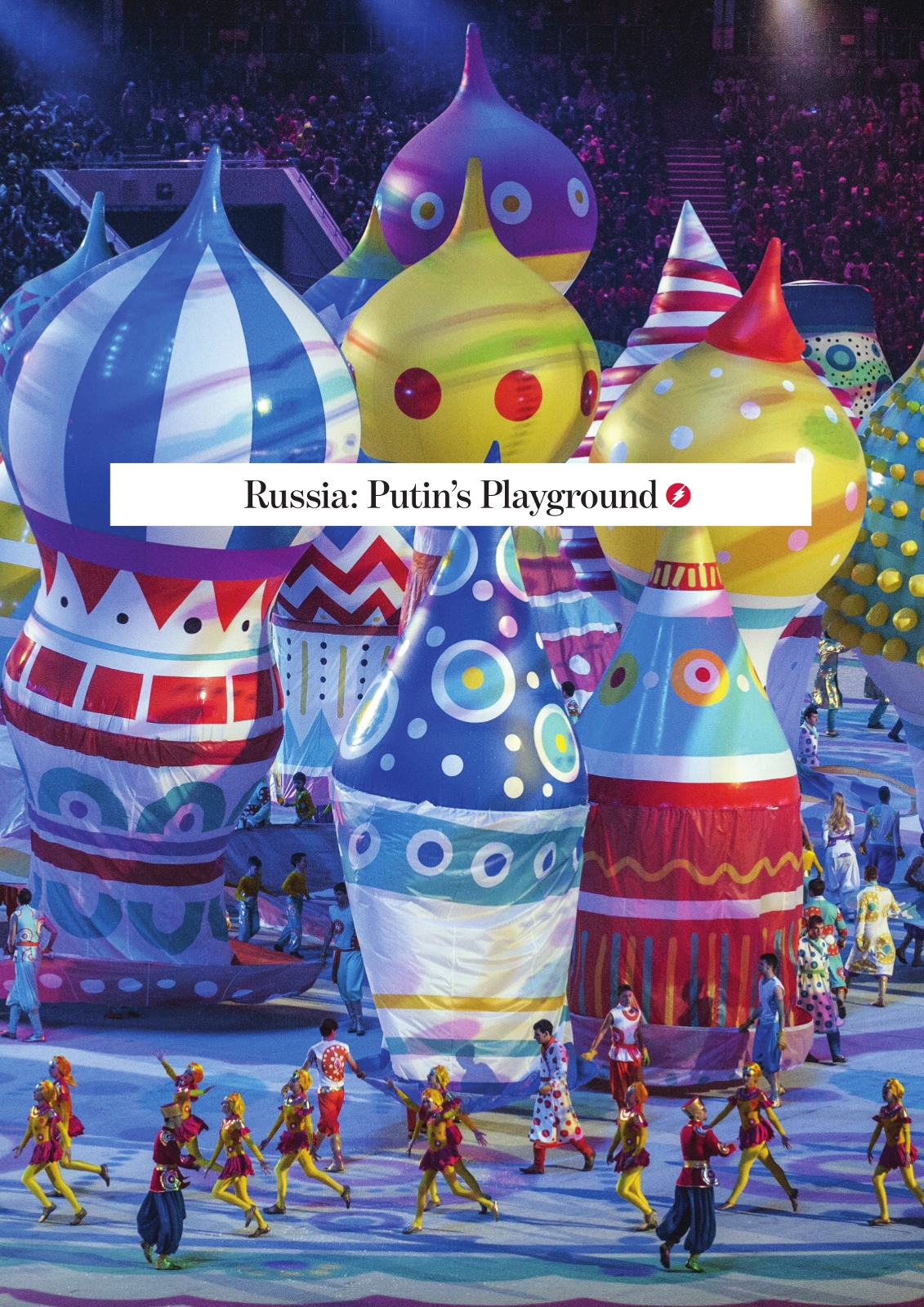

With Pomp and Putin

At Sochi the show must, and does, go on

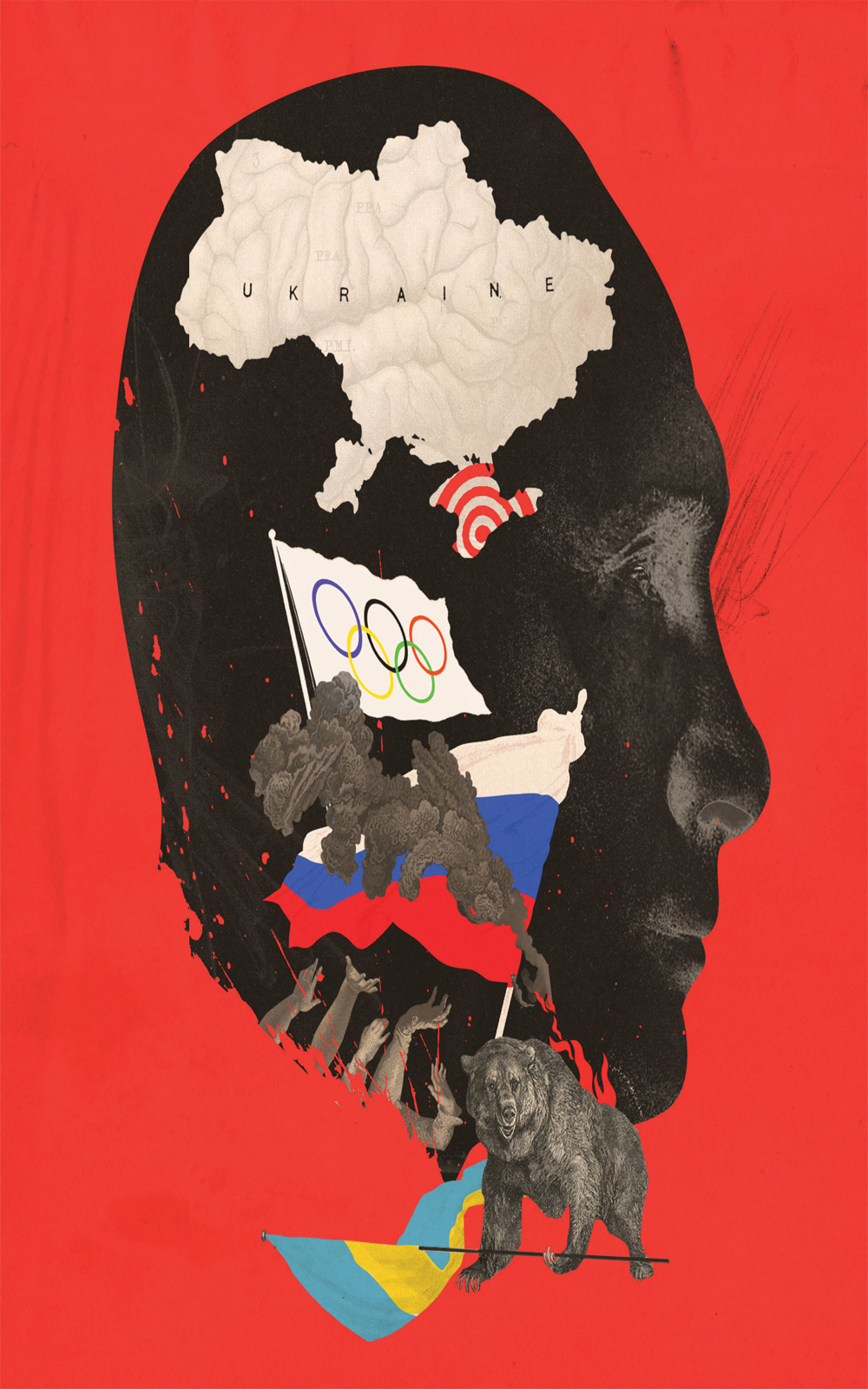

On February 7, 2014,Russia showed the world what the most expensive Olympic Games in history looked like. During the opening ceremony in Sochi, more than a hundred ballet dancers recreated an imperial ball based on a scene from War and Peace. A fluorescent troika (a traditional sleigh) carried a child above the stage, and letters of the Cyrillic alphabet flashed on a giant screen: N for Nabokov, S for Sputnik. The last time Russia hosted the Olympics, in 1980, the capitalist West boycotted them over the then-recent Soviet incursion into Afghanistan. Now, with 375 members, the American delegation was the largest, and their Russian hosts looked nothing like the sullen victims of crippling deficits and empty slogans of the Cold War era. Confident and well-dressed, they waved their new tricolor national flags and chanted Russia ecstatically. The only person who didnt look festive was Russian President Vladimir Putin. He had his reasons.

On February 7, 2014,Russia showed the world what the most expensive Olympic Games in history looked like. During the opening ceremony in Sochi, more than a hundred ballet dancers recreated an imperial ball based on a scene from War and Peace. A fluorescent troika (a traditional sleigh) carried a child above the stage, and letters of the Cyrillic alphabet flashed on a giant screen: N for Nabokov, S for Sputnik. The last time Russia hosted the Olympics, in 1980, the capitalist West boycotted them over the then-recent Soviet incursion into Afghanistan. Now, with 375 members, the American delegation was the largest, and their Russian hosts looked nothing like the sullen victims of crippling deficits and empty slogans of the Cold War era. Confident and well-dressed, they waved their new tricolor national flags and chanted Russia ecstatically. The only person who didnt look festive was Russian President Vladimir Putin. He had his reasons.

EMMANUEL POLANCO / COLAGENE.C0M 2015

As the cascades of triple axels and long jumps streamed out of Sochi, some eight hundred miles west, in Kiev, the capital of the now-independent Ukraine, protesters were demanding the resignation of the pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovich, who had rejected a package that would integrate Ukraine more closely with the European Union. On February 20, as Russia won another gold in ladies free skating, 88 people were shot dead in Kreschatik, Kievs main square. The protesters then took over the administrative buildings. Abandoned by his troops, President Yanukovich fled for Russia. The interim government vowed to resume Ukraines integration into the EU.

Is Russia in the hands of a lunatic? the pundits kept asking.

Is Russia in the hands of a lunatic? the pundits kept asking.

And that was that. A fellow Slavic nation, whose multicolored ribbons once flew so merrily in the circle dances during the shows of national unity, was now irrevocably drifting towards the West. It was no longer inconceivable that Ukraine might one day join NATO, as the other former Soviet republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania had already done; and yet it was on the Ukraines Crimean peninsula that the historical headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet (and Russias only remaining naval base in the region) were located.

Meanwhile, in Sochi, the show went on. At the closing ceremony, on February 23, an emotional International Olympic Committee president declared that Russia delivered all what it had promised. On February 27, unidentified troops seized the building housing the Supreme Council of Crimea. A month later, on March 18, Russia declared Crimea to be Russian territory.

The annexation of Crimea at last propelled Russia out of the sports segment and into prime-time news. As Western leaders grappled for a response, headlines like Putins Gambit, coupled with soaring approval ratings at home, gave the Russian president back the smug look he had so obviously missed in Sochi. He didnt shed this smugness when the medias dominant metaphor shifted from chess toward Nazi Germany, nor did he blink when the sanctions banned some of his closest oligarch friends from visiting their French Riviera villas. He continued to smile as the counter-sanctions squeezed Russias import-dependent economy, already staggering under falling oil prices, and as he watched the ruble lose half its value. Is Russia in the hands of a lunatic? the pundits kept asking. Why are the Russian people swapping, en masse, their Nike T-shirts for those with anti-Western rhetoric, while voicing near-unanimous approval for their president? Vladimir Putins agenda, both hidden and explicit, has been subject to intense speculation, as has been his ongoing ability to control Russia in the setting of a deteriorating economic environment. Yet Russia is not just Putin. It is the largest country in the world, whose long and violent history has engendered a unique set of attitudes and behaviors that, to the outside eye, seem indecipherable. This book probes into the reality beyond the headlines, focusing on the interplay between the countrys three main constituencies: the state, the people, and the dissenters, with special attention paid to Russias history, institutions, perceptions, and relationship with the rest of the world.

WRIT LARGE

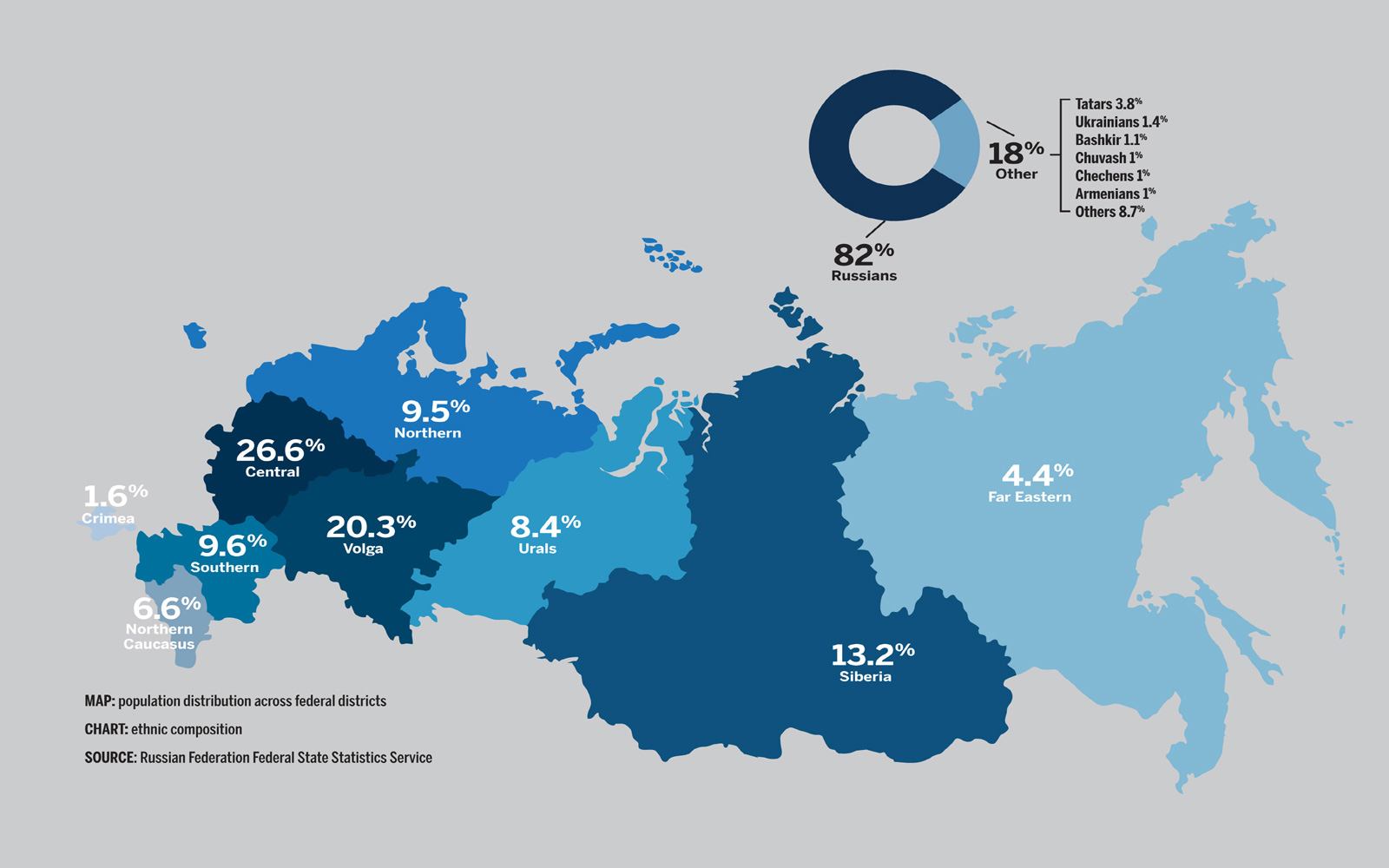

Despite its 146 million inhabitants, Russias enormity renders much of the country, especially Siberia and the Far Eastern District, relatively empty.

On February 7, 2014,Russia showed the world what the most expensive Olympic Games in history looked like. During the opening ceremony in Sochi, more than a hundred ballet dancers recreated an imperial ball based on a scene from War and Peace. A fluorescent troika (a traditional sleigh) carried a child above the stage, and letters of the Cyrillic alphabet flashed on a giant screen: N for Nabokov, S for Sputnik. The last time Russia hosted the Olympics, in 1980, the capitalist West boycotted them over the then-recent Soviet incursion into Afghanistan. Now, with 375 members, the American delegation was the largest, and their Russian hosts looked nothing like the sullen victims of crippling deficits and empty slogans of the Cold War era. Confident and well-dressed, they waved their new tricolor national flags and chanted Russia ecstatically. The only person who didnt look festive was Russian President Vladimir Putin. He had his reasons.

On February 7, 2014,Russia showed the world what the most expensive Olympic Games in history looked like. During the opening ceremony in Sochi, more than a hundred ballet dancers recreated an imperial ball based on a scene from War and Peace. A fluorescent troika (a traditional sleigh) carried a child above the stage, and letters of the Cyrillic alphabet flashed on a giant screen: N for Nabokov, S for Sputnik. The last time Russia hosted the Olympics, in 1980, the capitalist West boycotted them over the then-recent Soviet incursion into Afghanistan. Now, with 375 members, the American delegation was the largest, and their Russian hosts looked nothing like the sullen victims of crippling deficits and empty slogans of the Cold War era. Confident and well-dressed, they waved their new tricolor national flags and chanted Russia ecstatically. The only person who didnt look festive was Russian President Vladimir Putin. He had his reasons.

Is Russia in the hands of a lunatic? the pundits kept asking.

Is Russia in the hands of a lunatic? the pundits kept asking.