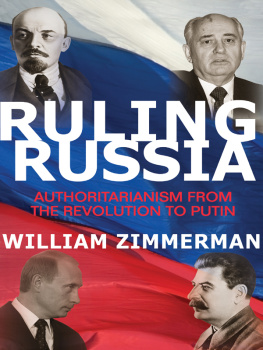

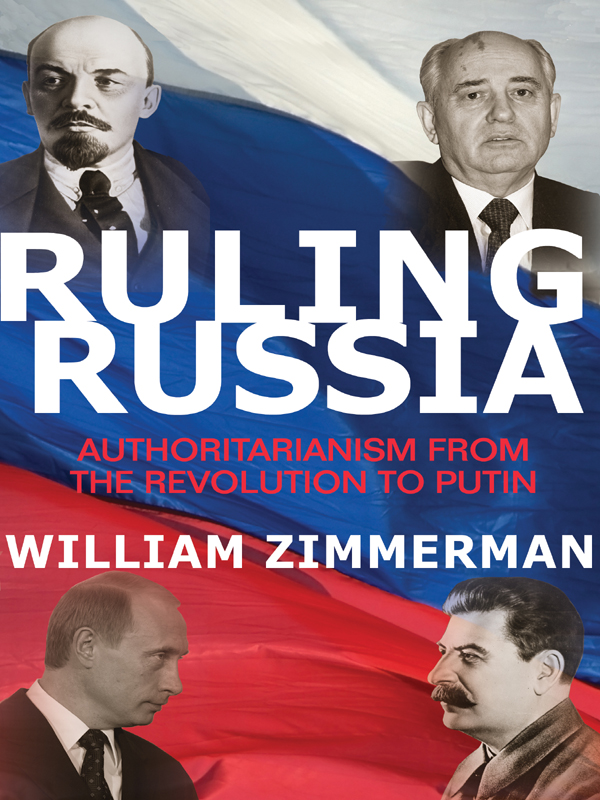

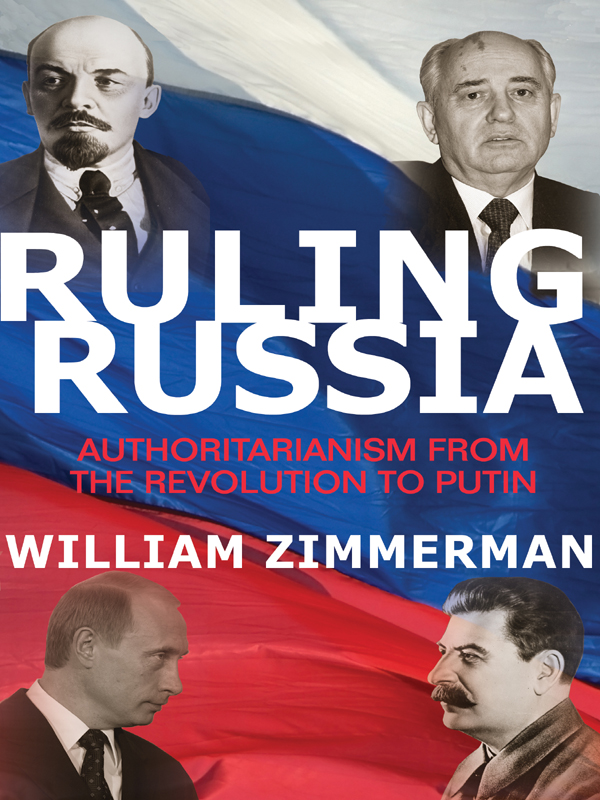

Ruling Russia

Ruling Russia

AUTHORITARIANISM FROM THE REVOLUTION TO PUTIN

William Zimmerman

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

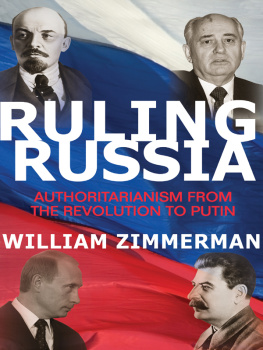

Jacket art: clockwise from top left:

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, ca. 1920, (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division); Mikhail Gorbachev in Aberdeen, on the occasion of receiving the Freedom of the City award, Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert/Alamy; Joseph Stalin, (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division); Vladimir Putin, Bratislava, Slovakia, 2005, Northfoto, courtesy of Shutterstock; Russian flag background Cattallina/Shutterstock.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zimmerman, William, 1936

Ruling Russia : authoritarianism from the revolution to Putin / William Zimmerman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16148-8 (hardback)

1. AuthoritarianismSoviet Union. 2. AuthoritarianismRussia (Federation) 3. DemocratizationRussia (Federation) 4. Soviet UnionPolitics and government. 5. Russia (Federation)Politics and government1991 I. Title.

JN6531.Z56 2014

320.947dc23 2013048288

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Palatino Linotype

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

IT TOOK ME SOME WHILE to write this book. In the process I incurred a number of debts. I and three former graduate studentsValerie Bunce, Olesya Tkacheva, and David Riveraconducted a workshop during which we discussed a draft of the first two-thirds of my book. I repeated the experience via videoconferencing with Russian colleaguesVladimir Gelman, Eduard Ponarin, Yegor Lazarev, and Kirill Kalinin. All provided valuable oral and written comments on my work at the stage I was in and provided me with useful suggestions about the directions I should take in completing the manuscript. It would not have been possible for me to conduct the two book conferences were it not for the financial support and vote of confidence I received from Teresa Sullivan, who was provost of the university when this project was launched, and the willingness of Vice Provost Lori Pierce to bear with my turgid pace after Professor Sullivan had departed Ann Arbor to become president of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville.

Rivera, Kalinin (currently an advanced graduate student at Michigan), and Tkacheva rendered further assistance in this projectRivera by providing me with detailed criticisms of every chapter, Kalinin by preparing the figures in , and Tkacheva by helping me with some transliteration issues. Kelly Grossmann provided valuable assistance in preparing the Selected Bibliography. In addition Kira Youdina exemplified the utility for students and faculty of the universitys Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program by chasing down fugitive sources and comparing Russian and English versions of key utterances by various early Bolsheviks.

Special words of thanks go to George Breslauer and Patrick Shields, both of whom made valuable comments on versions of the manuscript. As George has done on multiple occasions and in multiple roles in the course of half a century of friendship, he challenged me to sharpen my thinking about the book. Patrick had good ideas about the ways the manuscript could be improved and kept after me to finish the manuscript. An anonymous reviewer made useful substantive suggestions and also called my attention to ways the manuscript might be made more accessible to upper-division undergraduates.

Earlier versions of parts of some chapters have appeared previously. My comments about Marshal Sokolovsky first appeared as a review essay in the Journal of Conflict Resolution. My analysis of Russian citizen assessments of the strengths and attitudes of Russian leaders draws from an earlier Princeton University Press book (The Russian People and Foreign Policy, 2002). Undertaking empirically those questions would not have been possible had I not participated in a 199596 wave of mass surveys of which Timothy Colton was the principal investigator and if he had not shared data from subsequent surveys. My first effort to show systematically the trend away from mobilized participation and its consequences for the nature of the Soviet system came as a result of my participation in the Soviet Interview Project and appeared in James Millar, ed., Politics, Work, and Daily Life in the USSR ( Cambridge University Press, 1987). The section in which I report our ability to estimate changes in Soviet military spending first appeared as an article (coauthored with Glenn Palmer) in the American Political Science Review ( Cambridge University Press).

My wife, Susan McClanahan, supported me in multiple ways, most notably by graciously and in good humor accepting the fact that I have done in retirement what I did when I was drawing a salary from the University of Michigan.

This book would not have been possible without the advice, research, and friendship of my former students over the years. For that reason, I take particular pleasure in dedicating this book to them.

Bill Zimmerman

CENTER FOR POLITICAL STUDIES AND

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR

Ruling Russia

Introduction

THIS BOOK HAS its origins in a paper I wrote half a decade ago.

The project turned out differently than I expected. Thinking about whether Russia was a normal country helped me organize my thoughts about the evolution of Russian politics. I have used simple statistical measures in comparing the Russian Federation with other states. I I have consequently focused on a use of normality where it was most relevant to the purposes of a volume focusing on the historical evolution of Russian political systems, 19172013. I have in mind what leading Soviet and post-Soviet Russian figures advert to when they make reference to normal political systems or situations. It turns out there was a fundamental divide, but that divide was not between Soviet and post-Soviet Russian public figures. Rather, it was between those Soviet and Russian figures for whom normal signified stability, security, absence of change and, often, Russian uniqueness, and those for whom it connoted becoming a political system similar to those in the West or some part thereof.

Stability, security, and the status quo were what Gennady Yanayev, vice president of the USSR during the abortive August 1991 coup against Mikhail Gorbachev, had in mind when he referred to returning to normal conditions. It is what Vladimir Putin has generally had in mind as well when he has spoken of normal, though this was not universally the case especially in his first years as president. Examples of those who have had Western political systems in mind in referencing normal (read: Western) political systems would include such diverse public figures as Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, and the highly visible blogger Aleksei Navalny. (See below, pp. 196, 197, and 301 respectively.)

It turns out though equating normal with Western systems has generally not constrained Russian leaders from seeking to minimize the electoral uncertainty that is central to well-institutionalized Western electoral systems. Rather, Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and Putin all have used various artifices to create conditions characteristic of authoritarian systems where the incumbent is able to rest easy on the eve of elections.a democratic country at the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century than it had been at the onset of that decade.

Next page