First published 2001

This electronic edition published 2012

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire

GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright David Zimmerman, 2010, 2012

The right of David Zimmerman to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-4456-0061-1 (PRINT)

ISBN 978-1-4456-1249-2 (eBOOK)

To Elaine Zimmerman.

Thanks for everything, mom.

Love David

Contents

Chapter One

The Origins of Strategic Air Defence and Aircraft Early Warning

Chapter Two

Tuckers Acoustical Mirrors

Chapter Three

The Scientific, Political and Social Background to Radar

Chapter Four

The Discovery of Radar

Chapter Five

Committees and Politicians

Chapter Six

Orfordness and Bawdsey

Chapter Seven

The Tizard-Lindemann Dispute

Chapter Eight

Transforming the Air Defence System

Chapter Nine

Appeasement, Air Policy and Air Defence Research

Chapter Ten

Forging the Radar Chain

Chapter Eleven

The Phoney War

Chapter Twelve

The Battle of Britain

Chapter Thirteen

The Failure to Stop the Night-time Blitz

Foreword

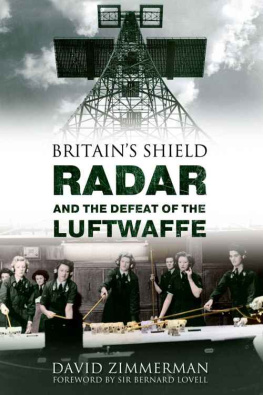

In the six years of the Second World War there were many great battles on land, sea and in the air that led to the ultimate Allied victory. Of these the Battle of Britain in 1940 remains the most celebrated more than half a century after the end of the great conflict. This battle is the centrepiece of David Zimmermans scholarly work, Britains Shield.

Anyone reading this book must be left gasping at the narrowness of the victory. In that famous phrase of Churchills speech when he reminded us how much we owed to the few, he was rightly paying tribute to the pilots of RAF Fighter Command, who, against the overwhelming odds of the Luftwaffe bombers, scored that crucial victory that led Hitler to cancel his invasion plans and thereby save Europe from Fascist domination.

It is the essence of Professor Zimmermans work that he both destroys and supports the many mythical beliefs that have become prominent about the events leading up to that historic victory in the summer of 1940. The radar chain around the coast was one essential component, for without that early warning system, Fighter Command would, undoubtedly, have been overwhelmed. That fact is common knowledge, but Zimmerman shows that it was the detailed integration of this early warning with the command structure of the RAF fighter squadrons that led to the ultimate success of fighter pilots. The filtering of the radar information, the allocation of action to the appropriate fighter group and the radio telephonic communication between fighters and ground control were essential elements in the critical years and months leading to the first great clashes of the air battle in July 1940.

The close association of the radar scientists with RAF personnel is revealed as another important element in the complex organisation leading to the ultimate encounter of fighter and bomber. Indeed, nowhere is that better illustrated than in the failure of the German command to recognize the importance of the radar chain. Goering refused to accept the advice of his intelligence chief General Martini that the radar stations should be destroyed. The relatively few attacks on the coastal radar chain reveal that had Goering accepted Martinis advice the outcome of the battle might well have been victory to the Luftwaffe. Indeed, the close integration of the British and Allied scientists with the operational commands, in contrast with that in Germany, was at that time and throughout the war, a significant factor in conflict.

Another refreshing feature of Professor Zimmermans book is the description of the evolution of the early warning system from the acoustic mirror and the abrupt change to the development of the radar system in the 1930s. Shortly after Baldwins warning that the bomber would always get through, Watson-Watt staged his famous Daventry demonstration to show that radio waves could be detected after reflection from a bomber. Wimperis, the scientific advisor to the Air Ministry, had recently convened the committee with Sir Henry Tizard to advise about the possibility of defence against the bomber. Zimmerman is the first historian to describe in detail the years of political intrigue in which the Tizard Committee became involved in their support of the development of radar.

The personnel conflict between Tizard and Professor Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell) has often been described. Here we find the detailed scientific and political facts underlying that conflict. Lindemann was Churchills wealthy friend and in his intrigue against the government Churchill ruthlessly used Lindemanns advice. It is truly an amazing story and Zimmerman shows how narrowly Tizard and scientific sanity prevailed over the machinations of the Churchill-Lindemann axis in those pre-war years.

Zimmerman ends his book on a rather sad note the failure of the RAF to defeat the blitz on London and other cities, when the Luftwaffe turned to night bombing after their defeat in the daytime battle of 1940. The sequence had been foreseen by Tizard and RAF Command and development of the airborne AI (Air Interception) radar for night fighters had commenced. The early prototypes rushed into action were a total failure. Zimmerman places the blame on the failure to engage the British electronics industries at this early stage. In fact, there were other fundamental problems that required another two years to overcome. It was not until the spring of 1941 before the scientific-industrial collaboration produced operational equipment that defeated the night bombers.

Meanwhile, there had been tragic loss of life in London and in other cities and the reader of this book may well feel regret that the RAF Commander-in-Chief and the scientists, who had been the inspiration and core of the shield that saved Britain in 1940, were either dismissed or neglected.

Sir Bernard Lovell, 2001

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Simon and Carolyn Chenery for accompanying me on several jaunts around the British coast visiting sites related to the history of the air defences. The staffs of the archives at Nuffield College, Churchill College, the Public Records Office and the Imperial War Museum provided invaluable assistance in providing me with access to the documentation and photographs required for this study. A special thanks to Sebastian Cox of the Air Historical branch for taking time out of his busy schedule to provide some useful sources and priceless advice. Thanks to David Hall for conducting research for me at the PRO. Also a special mention to Paul Mackenzie for his advice and his acquisition of a valuable photograph from the PRO. The Science Museum, after a long delay, provided me with photographs of the Daventry equipment. The