JENNY WILLIAMS

More Lives than One

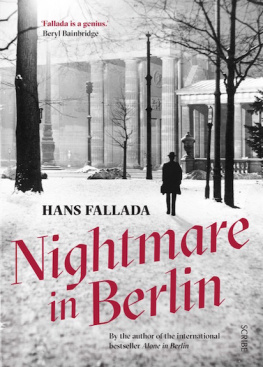

A Biography of Hans Fallada

PENGUIN BOOKS

For he who lives more lives than one

More deaths than one must die.

Oscar Wilde

Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

MORE LIVES THAN ONE

Jenny Williams is Professor Emeritus at Dublin City University. She has worked on Falladas life and writings for many years. Her biography is based on published and unpublished sources, including family letters and interviews.

List of Illustrations

Rudolf Ditzens parents, Elisabeth and Wilhelm Ditzen, c. 1900

With his sisters Elisabeth (left) and Margarete, c. 1896

As a schoolboy in Berlin, c. 1906.

His mother, Elisabeth Ditzen, 1910.

Before setting out on the Wandervogel trip to Holland in 1910.

Adelaide Ditzen, Rudolfs Aunt Ada, 1911.

As a sixth-former in Rudolstadt, c. 1911.

A postcard entitled Dukes Visit to Posterstein sent to his father in August 1914

Stable hand with horses on the Heydebreck estate in Eastern Pomerania, 1915.

Brothers Rudolf (left) and Uli Ditzen in Leipzig.

Brother Uli, shortly before his death in 1918.

Neumnster Prison.

Neumnster, 1929. Note on the reverse: In my office at the Association for Tourism and Commerce. Background: Posters!

Anna Ditzen (Suse) with son Uli in Neuenhagen, Berlin, September 1930.

Suse, October 1931.

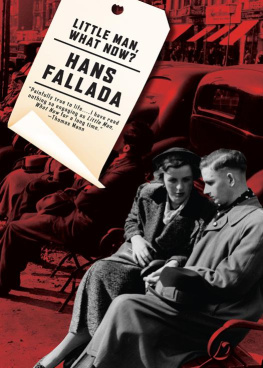

After the success of Little Man What Now?, August 1933.

The village of Carwitz (Aerial photo from a height of some 100 m) c. 1935. The arrow indicates the Ditzens smallholding.

In the new house in Carwitz on Suses birthday, 12 March 1934.

With Uli in a motor boat on Carwitz lake, August 1934.

Fun and games in the garden in Carwitz: Uli and Lore on top, their father on the ground (second from left), summer 1937.

At his desk in the study in Carwitz, leafing through the manuscript of Once We Had a Child, 1934.

View of the study, 1934. The telephone number was Feldberg 76

c. 1935.

Visitors to Carwitz: (from left) Heinrich Maria Ledig, Martha Dodd and Mildred Harnack, 27 May 1934.

With friend and psychiatrist Willi Burlage.

With Peter Zingler, who was in charge of foreign rights at Rowohlts, and Uli.

Sister and brother-in-law, Elisabeth and Heinz Hrig (extreme left), on holiday in St Peter on the North Sea.

Sophie Zickermann, nurse and long-standing family friend, summer 1936.

Publisher and friend Ernst Rowohlt (press photo, undated).

Press photo, 8 July 1939.

Family boat trip, July 1939.

With Suse in Carwitz, July 1943.

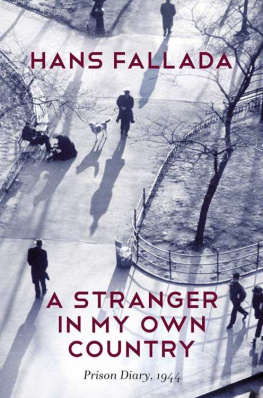

First page of the 1944 Prison Diary.

Second wife, Ulla Ditzen.

Ulla Ditzen with her daughter from her first marriage, Jutta Losch.

Deathbed photo (by Ruth Wilhelmi).

(Illustrations is from the private collection of Gunnar Mller-Waldeck.)

Introduction

This book is devoted to the life of a remarkable man among other things an alcoholic, drug addict, womanizer, jailbird and thief, in his time wooed by both the Nazi and the Soviet cultural authorities who in his novels chronicles the fate of a social class in a period of great upheaval and makes an eloquent plea for ordinary human decency and who, in the words of one of the heroes of his youth, discovered for himself that he who lives more lives than one/More deaths than one must die.

Hans Fallada was a best-selling German novelist of the early 1930s. His Kleiner Mann was nun? (Little Man What Now?) rescued the business of his publisher and friend Ernst Rowohlt from bankruptcy in 1932.

Falladas reputation has been as much at the mercy of political developments since his death in 1947 as it was during his lifetime. Yet his output novels, poems, short stories, letters, translations, reviews and childrens stories was prodigious, his observation of the contemporary scene acute, and his talent as a storyteller unsurpassed in twentieth-century German literature. Now, more than sixty years after his death, it is time to undertake a reassessment of a writer who lived a turbulent life in turbulent times and through it all maintained a belief in universal human values.

Hans Fallada was the pseudonym of Rudolf Ditzen, who published his first novel at the age of twenty-six under an assumed name ostensibly in order to spare his parents feelings. Ditzen relates that his pen name derived from characters in two of Grimms Fairy Tales: Hans, the happy-go-lucky simpleton in Lucky Hans and Fal(l)ada, the horse in The Goose Girl, who, even after he has been beheaded, continues to bear witness to the truth.

The adoption of a pen name had an additional and more complex significance: it permitted Rudolf Ditzen through the persona of Hans Fallada to create a world in which the conflicts and tensions of his life could be resolved. The pseudonym was thus cause and effect of the artistic process. In a radio broadcast in 1946 Ditzen declared: Everything in my life ends up in my books.

The strongly autobiographical dimension which is a striking feature of Ditzens writing is a further indication that the pseudonym Hans Fallada was not a mere stratagem to protect his family from publicity but was central to his artistic impulse. As we shall see, everything written under the name Hans Fallada was fiction even ostensibly autobiographical pieces. This biography, which views its subject not only as a writer but also as farmer, white-collar worker, husband and father, will therefore refer to him as Rudolf Ditzen since this is the name which he used in everyday life and by which he was known both inside and outside his immediate family circle.

Born on 21 July 1893, the son of a member of the Prussian judiciary who was later appointed to the German Imperial Supreme Court in Leipzig, Rudolf Ditzen was committed to a psychiatric hospital at the age of eighteen after killing a close friend in a duel. This was the first of many periods spent in psychiatric care. In the 1920s he served two prison sentences for theft and embezzlement; in 1933 he was arrested and held in custody by the SA, the Nazi Partys private army, or storm troop (Sturmabteilung); eleven years later he was imprisoned once again, on this occasion for the attempted murder of his first wife.

Ditzen chose to remain in Germany during the Nazi period. He never joined the Nazi Party, indeed he loathed all the strutting and posing, the corruption and the denunciations. However, he accommodated himself to the authorities to the extent that he rewrote the conclusion to one of his novels at Goebbelss behest, and as a major in the Reichsarbeitsdienst he undertook three officially sponsored tours to the Front in 1943 to gather material for the Nazi propaganda machine. Yet, when the Soviet army arrived in Mecklenburg in the spring of 1945, it installed him as mayor of Feldberg, his local town, where his duties included supervising the denazification effort.

Is this the life-story of a moral coward or a political opportunist or, even, a schizophrenic? Or is it representative of thousands upon thousands of Germans in the first half of the twentieth century? Momentous decisions, such as Rudolf Ditzens decision not to emigrate to England in 1938, were made without the benefit of hindsight. Should this make the judgement of posterity less harsh? Bertolt Brecht, in his poem To Those Born Later, begs future generations to remember him and his contemporaries with forbearance. Does this apply to Ditzen, too? Or was Thomas Mann right when he stated: any books which could be printed at all in Germany between 1933 and 1945 are worse than useless A stench of blood and shame attaches to them; they should all be pulped. To what extent can Ditzens lack of resistance to National Socialism be read as support? These are all questions which a biographer is obliged to address. Indeed, these are the very questions that make Rudolf Ditzen such a fascinating and challenging subject.

Next page