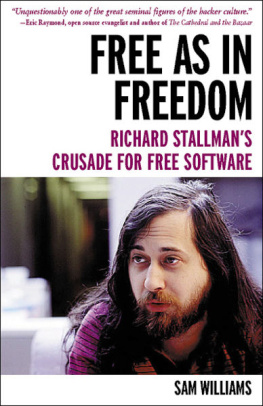

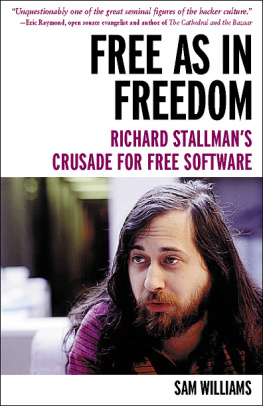

Free as in Freedom (2.0): Richard Stallman and the Free Software Revolution

Sam Williams

Second edition revisions by Richard M. Stallman

This is Free as in Freedom 2.0: Richard Stallman and the Free Software Revolution , a revision of Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallmans Crusade for Free Software .

Copyright 2002, 2010 Sam Williams

Copyright 2010 Richard M. Stallman

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled GNU Free Documentation License.

Published by the Free Software Foundation

51 Franklin St., Fifth Floor

Boston, MA 02110-1335

USA

ISBN: 9780983159216

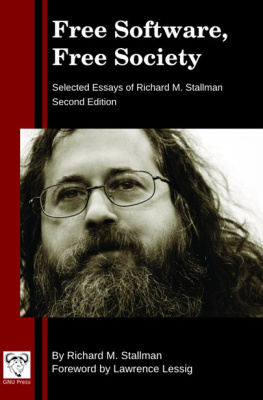

The cover photograph of Richard Stallman is by Peter Hinely. The PDP-10 photograph in Chapter 7 is by Rodney Brooks. The photograph of St. IGNUcius in Chapter 8 is by Stian Eikeland.

Contents

Foreword

by Richard M. Stallman

I have aimed to make this edition combine the advantages of my knowledge and Williams interviews and outside viewpoint. The reader can judge to what extent I have achieved this.

I read the published text of the English edition for the rst time in 2009 when I was asked to assist in making a French translation of Free as in Freedom . It called for more than small changes.

Many facts needed correction, but deeper changes were also needed. Williams, a non-programmer, blurred fundamental technical and legal distinctions, such as that between modifying an existing programs code, on the one hand, and implementing some of its ideas in a new program, on the other. Thus, the rst edition said that both Gosmacs and GNU Emacs were developed by modifying the original PDP-10 Emacs, which in fact neither one was. Likewise, it mistakenly described Linux as a version of Minix. SCO later made the same false claim in its infamous lawsuit against IBM, and both Torvalds and Tanenbaum rebutted it.

The rst edition overdramatized many events by projecting spurious emotions into them. For instance, it said that I all but shunned Linux in 1992, and then made a a dramatic about-face by deciding in 1993 to sponsor Debian GNU/Linux. Both my interest in 1993 and my lack of interest in 1992 were pragmatic means to pursue the same end: to complete the GNU system. The launch of the GNU Hurd kernel in 1990 was also a pragmatic move directed at that same end.

For all these reasons, many statements in the original edition were mistaken or incoherent. It was necessary to correct them, but not straightforward to do so with integrity short of a total rewrite, which was undesirable for other reasons. Using explicit notes for the corrections was suggested, but in most chapters the amount of change made explicit notes prohibitive. Some errors were too pervasive or too ingrained to be corrected by notes. Inline or footnotes for the rest would have overwhelmed the text in some places and made the text hard to read; footnotes would have been skipped by readers tired of looking down for them. I have therefore made corrections directly in the text.

However, I have not tried to check all the facts and quotations that are outside my knowledge; most of those I have simply carried forward on Williams authority.

Williams version contained many quotations that are critical of me. I have preserved all these, adding rebuttals when appropriate. I have not deleted any quotation, except in where I have deleted some that were about open source and did not pertain to my life or work. Likewise I have preserved (and sometimes commented on) most of Williams own interpretations that criticized me, when they did not represent misunderstanding of facts or technology, but I have freely corrected inaccurate assertions about my work and my thoughts and feelings. I have preserved his personal impressions when presented as such, and I in the text of this edition always refers to Williams except in notes labeled RMS:.

In this edition, the complete system that combines GNU and Linux is always GNU/Linux, and Linux by itself always refers to Torvalds kernel, except in quotations where the other usage is marked with [ sic ]. See http://www.gnu.org/gnu/gnu-linux-faq.html for more explanation of why it is erroneous and unfair to call the whole system Linux.

I would like to thank John Sullivan for his many useful criticisms and suggestions.

Preface by Sam Williams

This summer marks the 10th anniversary of the email exchange that set in motion the writing of Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallmans Crusade for Free Software and, by extension, the work prefaced here, Richard Stallman and the Free Software Revolution .

Needless to say, a lot has changed over the intervening decade.

Originally conceived in an era of American triumphalism, the books main storyline about one mans Jeremiah-like efforts to enlighten fellow software developers as to the ethical, if not economic, shortsightedness of a commercial system bent on turning the free range intellectual culture that gave birth to computer science into a rude agglomeration of proprietary gated communities seems almost nostalgic, a return to the days when the techno-capitalist system seemed to be working just ne, barring the criticism of a few outlying skeptics.

Now that doubting the system has become almost a common virtue, it helps to look at what narrative threads, if any, remained consistent over the last ten years.

While I dont follow the software industry as closely as I once did, one thing that leaps out now, even more than it did then, is the ease with which ordinary consumers have proven willing to cede vast swaths of private information and personal user liberty in exchange for riding atop the coolest technology platform or the latest networking trend.

A few years ago, I might have dubbed this the iPod Effect, a shorthand salute to Apple co-founder Steve Jobs unrivaled success in getting both the music industry and digital music listeners to put aside years of doubt and mutual animosity to rally around a single, sexy device the Apple iPod and its restrictive licensing regime, iTunes. Were I pitching the story to a magazine or newspaper nowadays, I d probably have to call it the iPad Effect or maybe the Kindle Effect both in an attempt to keep up with the evolving brand names and to acknowledge parallel, tectonic shifts in the realm of daily journalism and electronic book publishing.

Lest I appear to be gratuitously plugging the above-mentioned brand names, RMS suggests that I offer equal time to a pair of web sites that can spell out their many disadvantages, especially in the realm of software liberty. I have agreed to this suggestion in the spirit of equal time. The web sites he recommends are http://DefectiveByDesign.org and http://BadVista.org .

Regardless of title, the notion of corporate brand as sole guarantor of software quality in a swiftly changing world remains a hard one to dislodge, even at a time when most corporate brands are trading at or near historic lows.

Ten years ago, it wasnt hard to nd yourself at a technology conference listening in on a conversation (or subjected to direct tutelage) in which some old-timer, Richard Stallman included, offered a compelling vision of an alternate possibility. It was the job of these old-timers, I ultimately realized, to make sure we newbies in the journalism game recognized that the tools we prided ourselves in nally knowing how to use Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, Internet Explorer, just to name a few popular offerings from a single oft-cited vendor were but a pale shadow of towering edice the original architects of the personal computer set out to build.