Richard Stallman is the prophet of the free software movement. He understood the dangers of software patents years ago. Now that this has become a crucial issue in the world, buy this book and read what he said.

Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web

Richard Stallman is the philosopher king of software. He single-handedly ignited what has become a world-wide movement to create software that is Free, with a capital F. He has toiled for years at a project that many once considered a fools errand, and now that is widely seen as inevitable.

Simon L. Garfinkel, computer science author and columnist

By his hugely successful efforts to establish the idea of Free Software, Stallman has made a massive contribution to the human condition. His contribution combines elements that have technical, social, political, and economic consequences.

Gerald Jay Sussman, Matsushita Professor of Electrical Engineering, MIT

RMS is the leading philosopher of software. You may dislike some of his attitudes, but you cannot avoid his ideas. This slim volume will make those ideas readily accessible to those who are confused by the buzzwords of rampant commercialism. This book needs to be widely circulated and widely read.

Peter Salus, computer science writer, book reviewer, and UNIX historian

Richard is the leading force of the free software movement. This book is very important to spread the key concepts of free software world-wide, so everyone can understand it. Free software gives people freedom to use their creativity.

Masayuki Ida, professor, Graduate School of International Management, Aoyama Gakuin University

Free Software, Free Society

______________

Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman

Second Edition

Richard M. Stallman

_______________________________________________

This is the second edition of Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman.

Free Software Foundation

51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor

Boston, MA 02110-1335

Copyright 2002, 2010 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire book are permitted worldwide, without royalty, in any medium, provided this notice is preserved. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this book from the original English into another language provided the translation has been approved by the Free Software Foundation and the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies.

ISBN 978-0-9831592-0-9

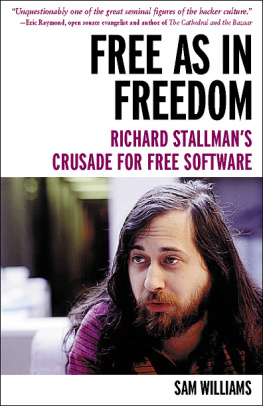

Cover design by Rob Myers.

Cover photograph by Peter Hinely.

Contents

I

II

15 Did You Say Intellectual Property?

Its a Seductive Mirage

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

A

B

Foreword

Copyright 2002 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This foreword was originally published, in 2002, as the introduction to the first edition. This version is part of Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman, 2nd ed. (Boston: GNU Press, 2010).

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire chapter are permitted worldwide, without royalty, in any medium, provided this notice is preserved.

__________________________

Every generation has its philosophera writer or an artist who captures the imagination of a time. Sometimes these philosophers are recognized as such; often it takes generations before the connection is made real. But recognized or not, a time gets marked by the people who speak its ideals, whether in the whisper of a poem, or the blast of a political movement.

Our generation has a philosopher. He is not an artist, or a professional writer. He is a programmer. Richard Stallman began his work in the labs of MIT, as a programmer and architect building operating system software. He has built his career on a stage of public life, as a programmer and an architect founding a movement for freedom in a world increasingly defined by code.

Code is the technology that makes computers run. Whether inscribed in software or burned in hardware, it is the collection of instructions, first written in words, that directs the functionality of machines. These machinescomputersincreasingly define and control our life. They determine how phones connect, and what runs on TV. They decide whether video can be streamed across a broadband link to a computer. They control what a computer reports back to its manufacturer. These machines run us. Code runs these machines.

What control should we have over this code? What understanding? What freedom should there be to match the control it enables? What power?

These questions have been the challenge of Stallmans life. Through his works and his words, he has pushed us to see the importance of keeping code free. Not free in the sense that code writers dont get paid, but free in the sense that the control coders build be transparent to all, and that anyone have the right to take that control, and modify it as he or she sees fit. This is free software; free software is one answer to a world built in code.

Free. Stallman laments the ambiguity in his own term. Theres nothing to lament. Puzzles force people to think, and this term free does this puzzling work quite well. To modern American ears, free software sounds utopian, impossible. Nothing, not even lunch, is free. How could the most important words running the most critical machines running the world be free. How could a sane society aspire to such an ideal?

Yet the odd clink of the word free is a function of us, not of the term. Free has different senses, only one of which refers to price. A much more fundamental sense of free is the free, Stallman says, in the term free speech, or perhaps better in the term free labor. Not free as in costless, but free as in limited in its control by others. Free software is control that is transparent, and open to change, just as free laws, or the laws of a free society, are free when they make their control knowable, and open to change. The aim of Stallmans free software movement is to make as much code as it can transparent, and subject to change, by rendering it free.

The mechanism of this rendering is an extraordinarily clever device called copyleft implemented through a license called GPL. Using the power of copyright law, free software not only assures that it remains open, and subject to change, but that other software that takes and uses free software (and that technically counts as a derivative) must also itself be free. If you use and adapt a free software program, and then release that adapted version to the public, the released version must be as free as the version it was adapted from. It must, or the law of copyright will be violated.

Free software, like free societies, has its enemies. Microsoft has waged a war against the GPL, warning whoever will listen that the GPL is a dangerous license. The dangers it names, however, are largely illusory. Others object to the coercion in GPLs insistence that modified versions are also free. But a condition is not coercion. If it is not coercion for Microsoft to refuse to permit users to distribute modified versions of its product Office without paying it (presumably) millions, then it is not coercion when the GPL insists that modified versions of free software be free too.

And then there are those who call Stallmans message too extreme. But extreme it is not. Indeed, in an obvious sense, Stallmans work is a simple translation of the freedoms that our tradition crafted in the world before code. Free software would assure that the world governed by code is as free as our tradition that built the world before code.

Next page