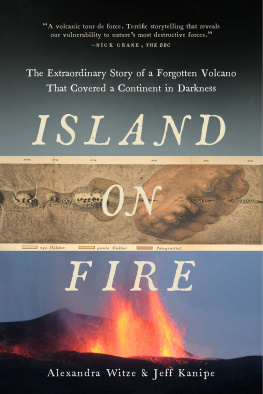

ISLAND ON FIRE

The Extraordinary Story of a Forgotten Volcano That Changed the World

Alexandra Witze & Jeff Kanipe

Contents

ISLAND ON FIRE

T HIS BOOK DESCRIBES AN EXTRAORDINARY volcanic eruption that took place in Iceland starting in June 1783. In August 2014, a miniature version of these events began unfolding before our eyes in the same country.

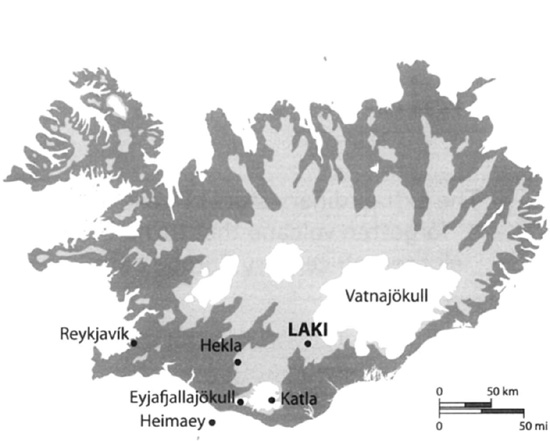

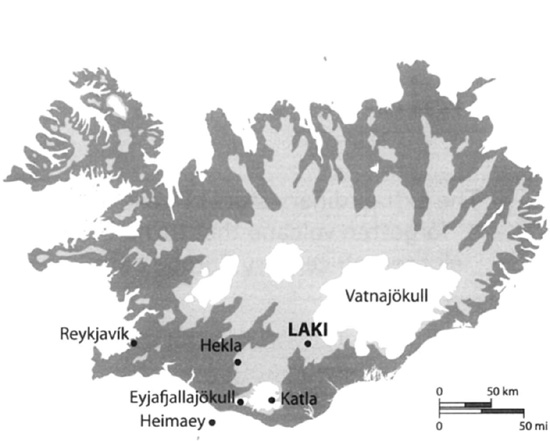

Not too far from Laki, near a mountain called Brarbunga, the ground ripped open and began spouting fire. Fountains of lava soared skyward along a long, straight tear in the landscape. Molten rock oozed, forming a massive tongue of lava that took the easiest course downhill: it flowed into the bed of a nearby river and began making its way toward the sea. This is precisely what happened with Laki, though in a far greater scale, in the summer of 1783.

The first few weeks of the 2014 Brarbunga eruption were nothing short of enchanting. Thanks to webcams installed around the mountain, anyone with an Internet connection could watch the fiery action. Plumes of steam billowed from the fissure. Curtains of flame rose into action and then died back. At night, the blue-green glow of the aurora borealis danced above the vivid red-orange landscape.

Yet Brarbungas otherworldly beauty obscured a more serious problemthe poisonous gases it was putting into the air. Scientists working near the flowing lava had to wear gas masks and carry monitors to track concentrations of sulfur dioxide in the air. Time and again they evacuated to a safe distance until the eruption subsided. Across eastern Iceland, air quality degraded and officials began warning people with breathing problems to stay inside. Atmospheric sensors recorded some of the highest levels of volcanic pollution ever recorded in the country, and shifting winds occasionally carried the mess toward Norway and Scotland.

As of this writing, the Brarbunga eruption had not done anything beyond spurting lava from several places along a fissure. It retained the possibility that it could get much, much worseperhaps by moving its eruption under the ice, with the accompanying dangers of glacial floods and towering plumes of ash. But no matter what Brarbungas end story turns out to be, the eruption has served as the latest reminder of what Icelandic volcanoes can do.

Well before this book was first published in London in the spring of 2014, the UK government had been thinking seriously about how to prepare for volcanic hazards. Top advisers in the Cabinet Office believe that the government needs to be prepared for two possible scenarios. One is a potential repeat of what happened in April 2010, when the Eyjafjallajkull volcano sent ash streaming into European airspace and grounded commercial flights for days. Society has already lived through that once, and so the government knows what to prepare for.

The other possibility is a gas-rich eruption that lasts for many monthsin other words, a repeat of what happened at Laki in 1783. The Cabinet Office has commissioned a detailed study of the possible consequences (see bit.ly/lakiscenario). It includes the latest computer modeling techniques to determine how sulfur dioxide and other pollutants would spread across the UK if something like Laki erupted again.

It makes sense for Britain to be concerned, because they sit essentially in the front row of any attack of Icelandic eruptions. Why, then, should Americans worry about such volcanoes?

For starters, anyone who lived in the western United States in May 1980 knows what the Cascades volcano range can do. In an eruption so powerful it starded even the scientists monitoring it, Mount St. Helens blew its top, killing 57 people. Experts say the risk persists at other Cascades volcanoes such as Mount Rainier, near Seattle.

Volcanoes are less a way of life in the United States than they are in Iceland, but they affect us all. In this globally connected world, what happens at remote volcanoes doesnt stay at remote volcanoes. Disruptions ripple outward in many formsearthquakes, tsunamis, poisonous gases, and climate changereminding us of what the planet has in store.

The two of us live in Colorado, not too far from one of the greatest single eruptions ever known. About 27 million years ago, the San Juan volcanic field erupted roughly 5,000 cubic kilometers of ash and debris. Today much of that material has turned to rock known as the Fish Canyon Tuff, found in the southwestern part of the state. Our volcanic history is never far away. Most likely, neither is yours.

Alexandra Witze and Jeff Kanipe

Boulder, Colorado

A T LEAST EVERYONE WAS AT HOME , snug in their beds, when the world began to end.

It was late January, 1973, and the harsh Icelandic winter had been even rougher than usual on Heimaey, an island off the countrys southern coast. On a normal night, Heimaeys fishermen would be out plying the rich waters of the North Atlantic for cod, haddock and herring. But on this night, high winds and stormy seas had kept the crews off their boats. Instead, they hunkered down in the trim little clapboard houses that sprawled above the islands spectacular black-cliffed harbour. So when the earth ripped open on 23 January, nearly all of Heimaeys 5,300 residents were there to see it.

It began just before 2 a.m., in a field on the islands eastern side. Only 200 metres from a serene little hamlet called K rkjubr,, or Church Farm, a line of flame spouted from the ground. It looked like a fire in dry grass, but of course it wasnt: it was the Earths crust coming apart, spewing fountains of lava into the air. Within minutes the spouts of fire were 150 metres high. Within hours the rift was 1.5 kilometres long, almost splitting the island in two.

rkjubr,, or Church Farm, a line of flame spouted from the ground. It looked like a fire in dry grass, but of course it wasnt: it was the Earths crust coming apart, spewing fountains of lava into the air. Within minutes the spouts of fire were 150 metres high. Within hours the rift was 1.5 kilometres long, almost splitting the island in two.

Had the eruption begun just a few hundred metres to the west, the volcano might have incinerated islanders as they slept. As it was, most of them found out about it when neighbours or police started pounding on their doors. Dazed, they staggered outside and stared at the fiery jets as close as the end of their street. Then they turned their backs, went inside and started packing.

In those first confused hours, no one knew what might happen to Heimaey. Would the eruption ignite the oil tanks down by the harbour? Would the entire town be engulfed by lava? Families grabbed what they could and made their way to the waterfront. One musician reportedly left wearing his pyjamas, clutching a frozen leg of lamb. Farmers at Church Farm shot their cows to spare their suffering, then fled.

Icelands civil patrol sprang into action. They had practiced for just such an emergency, and the evacuation went swiftly and smoothly. Between 3 a.m. and 7 a.m. nearly all of the islands residents left Heimaey - via the fishing fleet that fortuitously had been left in the harbour, or via planes sent from Reykjavk. Those who left knew they might never return. Those who stayed knew they faced a battle like nothing before.

Seen in retrospect, its not surprising that the eruption happened where and when it did. Heimaey is the biggest in a chain known as the Vestmannaeyjar or Westman Islands, named after the Celtic west men who fled here in the ninth century after murdering one of Icelands first permanent settlers. Volcanism is a way of life here; the islands are the tips of mostly dormant volcanoes poking above the waves.

rkjubr,, or Church Farm, a line of flame spouted from the ground. It looked like a fire in dry grass, but of course it wasnt: it was the Earths crust coming apart, spewing fountains of lava into the air. Within minutes the spouts of fire were 150 metres high. Within hours the rift was 1.5 kilometres long, almost splitting the island in two.

rkjubr,, or Church Farm, a line of flame spouted from the ground. It looked like a fire in dry grass, but of course it wasnt: it was the Earths crust coming apart, spewing fountains of lava into the air. Within minutes the spouts of fire were 150 metres high. Within hours the rift was 1.5 kilometres long, almost splitting the island in two.