Table of Contents

For my mother and father, Doris and Bernard Wortman

And generations unfulfilled,

The heirs of all we struggled for,

Shall here recall the mythic war,

And marvel how we stabbed and killed,

And name us savage, brave, austere

And none shall think how very young we were.

FROM ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, ON A MEMORIAL STONE

INTRODUCTION

Europe and America, 1916

How Very Young We Were

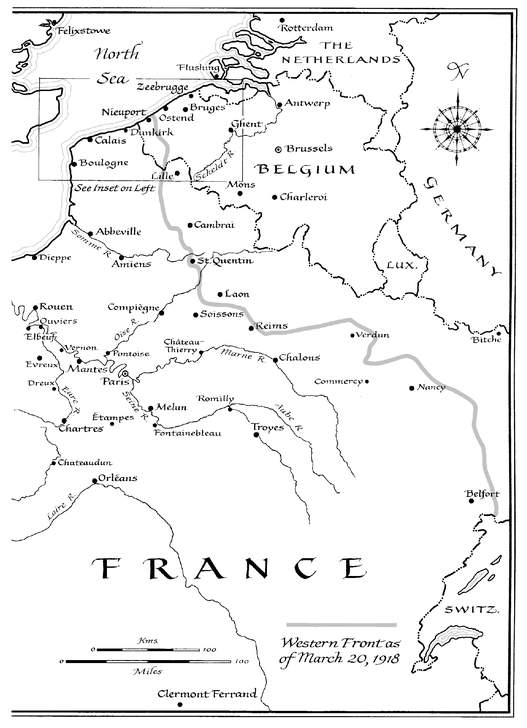

I N 1916, TWO YEARS INTO THE BLOODIEST WAR THE WORLD HAD YET SEEN, nearly half of the 9 million soldiers, sailors, and airmen and 5 million civilians who would be killed in the First World War already lay dead. Still, from the skies over London to the depths of the North Sea, and from the snowy steppes of Russia to the deserts of Mesopotamia, and all along the 450-mile Western Front, the cataclysmic attrition of the forces of Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and their alliesthe Central Powersand of the Allied armies of France, Great Britain, Russia and Italy would not abate. The worlds first truly global conflict had sucked nation after nation down into its murderous vortex. Some 65 million men were at arms, more than all previous wars combined. The front lines convulsed with bloody clashes that massacred 5,000 men on average every single daybut the opposing forces barely advanced.

Only one great power remained aloof, regarding the dreadful slaughter from afar: America. The 3,000-mile barrier of the Atlantic Ocean kept the horrors of the war far removed from the lives of most Americans. The occasional sinking of ships near American ports increasingly poisoned U.S.-German relations, but not even the infamous torpedoing of the British passenger liner the Lusitania as it steamed from New York to Liverpool could rouse a distracted people to war or shift the government from its policy of strict neutrality.

The United States had not fought a large-scale war of massed armies since the Civil War a half century earlier. With its nineteenth-century-style standing army smaller than the Great War combatants lost in a typical months fighting, a sparse navy charged with defending the nations thousands of miles of coastline and an air force smaller than Bulgarias or the Belgian forces that had escaped German occupation, the United States was ill-prepared to fight even a small-scale war.

Instead, other matters occupied the mind of a fast-changing, swift-moving nation. America was building. With its own internal frontiers awaiting conquest, the nation was racing ahead with a commercial exuberance that spread across a vast, largely untapped landscape. Wall Street financiers drove a blinding pace of consolidation and expansion, and business and industry boomed like never before. New factories opened and then expanded. Locomotives carried passengers and goods coast-to-coast at record speeds. Drivers ventured out along a growing network of paved roads. Shoppers with money to spend enjoyed an ever-expanding array of goods at glittery new retail emporiums. Motion picture-goers delighted at the exploits of Charlie Chaplins Little Tramp. And sports fans marveled at the hitting prowess shown by a young Boston Red Sox pitching star named Babe Ruth. A veritable tidal wave of European immigrants, many fleeing war and oppression in their former homelands, was further flooding the New Worlds already teeming urban neighborhoods. The new Americans came looking for opportunity, with a drive to succeed in a land of freedom from oppressive ancient regimes. The result was the creation of unprecedented wealth and a people preoccupied with the business of the day.

Why should America mix itself up in a brutal war between the Old Worlds royal powers?

A few outward-looking Americans, though, believed that sooner or later their nation would be drawn into the fight. At the dawn of the modern age, no country remained an island. Oceans that had once seemed insurmountable barriers could now be crossed in a matter of days. Americas growing wealth depended on the free movement of goods to trading partners worldwide. The foreign war would soon strangle world commerce, which was the lifeblood of American growth. Already an industrial giant, America was racing toward what many recognized would prove to be a decisive, hemispheric shift in global affairs. A few loud voices predicted the United States would have no choice but to fight.

Although their warnings went largely unheeded in government circles, a group of determined eighteen-, nineteen-, and twenty-year-old boys decided they would try to do something about the situation. Mostly college students from Yale University, they were the sons of Americas early twentieth-century aristocracyone a Rockefeller, one whose father headed the Union Pacific railroad empire, another J. P. Morgans partner. Others traced their roots to the Mayflower, several counted friends and relatives among presidents and statesmen, and some were famed collegiate athletes. All were fabulously wealthy. Leading members of the group included Bob Lovett, Trubee Davison, Di Gates, Crock Ingalls, Kenney MacLeish, and Al Sturtevant. Despite their youth, they had grown up in a time when their elite position brought with it special responsibilities that may seem distant to us today. They were schooled in heroism, made ready as schoolboys for leadership and sacrifice, even before their nation called upon them.

Fascinated by the new sport of motorized flight, and dimly aware of its growing military importance, they decided to create their own flying militia. In total, twenty-eight young men would pioneer military aviation, on their own initiative and with their families immense private resources forming the First Yale Unitwhat began as a college aero club became the originating squadron of the U.S. Naval Air Reserve. From there, many of these boys emerged as war heroes, and all served as leaders in Americas entry into a new dimension. Their every move caught the attention of a nation and inspired other young men across the country to follow their lead.

For a military ill-prepared to fight in the air, the Millionaires Unit, as a fascinated press dubbed the squadron, provided the nucleus of the burgeoning navy air corps. Although some were still just teens, all would become officersin some instances with thousands of men under their command. Most faced death daily in the battle for Europe. One planned the nations first strategic bomber force and headed its first night bomber wing. Another became the navys only Air Ace of the war. A few would never return. When America finally went to war, Admiral William Sims, commander of the U.S. Navy in Europe during the First World War, credited them as twentieth-century Paul Reveres. Following the Armistice, a grateful nation commended their foresight and courage. The rest of the world marveled: one of the finest and largest air services had grown out of what amounted to little more than a summer camp hosted by a group of college sophomores.

Those who returned home lost neither their love of flying nor their belief in its crucial role in any future military conflict. Members of the unit continued to lead in the dawning years of civilian aviation and throughout the interwar years of waning military aerial power. Their heroism and initiative during the First World War was not forgotten. Later, when America entered into World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt recalled nearly all of the former flyers to service. He was tapping old friends and comrades. He had come to know them well even before the First World War when he was a young assistant secretary of the Navy. After nearly twenty-five years on an isolationist, peacetime military footing, they again faced the complex and daunting task of creating a modern air force capable of knocking down a far better-prepared foe.