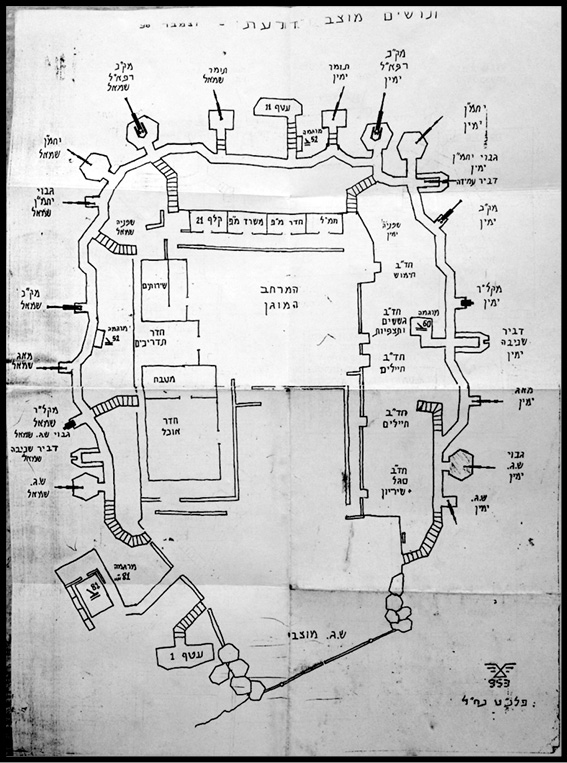

A map of the Pumpkin distributed to soldiers (1998)

Contents

NIGHTS ON THE hill were unusually long. They were inhabited by shadows flitting among boulders, by bushes that assumed human form, by viscous mists that crept in and thickened until all the sentries were blind. Sometimes you took over one of the guard posts, checked your watch an hour later, and found that five minutes had passed.

The enemy specialized in the roadside bomb artfully concealed, in the short barrage, in the rocket threaded through the slit of a guard post. We specialized in waiting. An honest history of this time would consist of several thousand pages of daydreams and disjointed thoughts born of exhaustion and boredom, disrupted only every hundred pages or so by a quick tragedy, and then more waiting.

At night four sentries waited in four guard posts that were never empty. Four crewmen waited in a tank, searching the approaches to the fort. Ambush teams conversed in whispers and passed cookies around in the undergrowth outside, waiting for guerrillas. A pair of soldiers drank coffee from plastic cups in a room of radio sets, waiting for transmissions to come through.

Before the earliest hint of dawn each day someone went around rousing all of those who werent awake already. Groggy creatures dropped from triple-decker bunks, struggled into their gear, and snapped helmet straps under chins. Now everyone was supposed to be ready. Lebanon was dark at first, but soon the sky began to pale through the camouflage net. Sometimes first light would reveal that the river valley had filled with clouds, and then the Pumpkin felt like an island fortress in a sea of mistlike the only place in the world, or like a place not of this world at all. There was a mood of purposefulness at that hour, an intensity of connection among us, a kind of inaudible hum that I now understand was the possibility of death; it was exciting, and part of my brain misses it though other parts know better.

This ritual, the opening act of every day, might have been called Morning Alert or some other forgettable military term, with any unnecessary syllable excised. It might have been shortened, as so much of our language was, to an acronym. But for some reason it was never called anything but Readiness with Dawn. The phrase is as strange in the original Hebrew as in the English. This was, in our grim surroundings, a reminder that things need not be merely utilitarian. It was an example of the poetry that you can find even in an army, if youre looking.

The hour of Readiness with Dawn was intended as an antidote to the inevitable relaxing of our senses, a way of whetting the garrisons dulled attention as the day began. It was said this was the guerrillas preferred time to storm the outpost, but they didnt do that when I was there. I remember standing in the trench as the curtain rose on our surroundings, trying to remember that out there, invisible, was the enemy, but finding my thoughts wandering instead to the landscape materializing at that moment beyond the coils of wire: cliffs and grassy slopes, villages balanced on the sides of mountains, a river flowing beneath us toward the Mediterranean. Things were so quiet that I believe I could hear the hill talking to me. Im not sure I could understand then what it was saying. But now I believe it was What are you doing here? And also Why dont you go home?

That hill is still speaking to me years later. Its voice, to my surprise, has not diminished with the passage of time but has grown louder and more distinct.

This book is about the lives of young people who finished high school and then found themselves in a warin a forgotten little corner of a forgotten little war, but one that has nonetheless reverberated in our lives and in the life of our country and the world since it ended one night in the first spring of the new century. Anyone looking for the origins of the Middle East of today would do well to look closely at these events.

Part 1 is about a series of incidents beginning in 1994 at the Israeli army outpost we called the Pumpkin, seen through the eyes of a soldier, Avi, who was there before me. Part 2 introduces two civilians, mothers, who helped bring about the unraveling of the militarys strategy. Part 3 describes my own time on the hill, and the experiences of several of my friends in the outposts last days. The final part recounts my return to Lebanon after these events had ended, in an attempt to understand them better.

Readiness with Dawn ended up being a time for contemplation. Look around: Where are you, and why? Who else is here? Are you ready? Ready for what? So important was this ritual at such an important time in my life that this mode of consciousness became an instinct, the way an infant knows to hold its breath underwater. I still slip into it often. Im there now.

Part One

AT AN ENCAMPMENT imposed upon the sand near an empty highway, teenagers lined up in a yard. There were perhaps three hundred of them, and in their floppy sunhats they looked like comical green mushrooms sprouting in rows from the tarmac. The conventions of military writing seem to require that they be described from now on as men. But this would hardly have applied a few days earlier.

Someone read from a list, and two dozen strangers whose names were called became a platoon of engineers. This, at least, was how one of the military clerks might have explained what had just happened. What had in fact been determined was the courseand, in a few cases, the durationof their lives. What led them here? The shuffling of forms in distant offices, the nature of their upbringing and youthful motivations, the astonishing progression of their peoples history in the century approaching its end. It didnt matter now. Some would break and vanish in the coming months, but the restfrom now on their fates were welded to one another and to the hilltop at the center of this story. It was early in the spring of 1994. Do you have to, do you have to, do you have to let it linger... You remember.

Avi was another figure in a row: shorter than most, more solid than most, a combative black-eyed flash suggesting he was less obedient than most. What was he doing among the others? He disliked authority and it was mutual, the nature of their relationship traceable to an incident a decade earlier. He and his classmates were to give a little bow during a visit by the president of Israel, Avi refused, his parents were summoned, and he said, I will not bow down. Perhaps he had been paying overly close attention to a book; the incident sounds like it may have been inspired by the character of Mordechai from the book of Esther. He was six or seven at the time.

This sort of thing recurred in subsequent years. He was supposed to be studying in the months leading up to the date of his draft, but one day when he should have been in class his parents found him instead sitting outside with a cigarette in one hand and, in the other, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. He became an individual early. Long before he turned eighteen and was summoned to his three years of military service, he had developed the habit of standing to one side and watching everyone, including himself. Much later some of Avis friends were able to see what happened to them in those years in the army from a distance, and they grasped their own place in the confusing sweep of events, but none had that ability at the time. Avi did. It didnt make things easier for him.