Copyright 2003 by Jack Nisbet

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Sasquatch Books

Cover design: Bob Suh

Interior design and composition: Stewart A. Williams

Cover map: David Thompson. Map of North America from 84 West, 1804. Map courtesy of

The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

Cover illustration: John Kirk. Ornithology of the United States of North America. Plate 1. 1839,

California Vulture. Illustration courtesy of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale

Stewart Library, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

All interior illustrations by Marjorie C. Leggitt except for:

: Head of a Vulture from the Journal of Meriwether Lewis, February 17, 1806, Codex J. p. 80.

Production editor: Heidi A. Schuessler

Copy editor: Don Graydon

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Nisbet, Jack, 1949

Visible bones : journeys across time in the Columbia River country / Jack Nisbet.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-57061-376-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 10: 1-57061-524-1 / ISBN 13: 978-1-57061-524-5 (paperback)

eBook ISBN: 978-1-57061-953-3

Columbia River ValleyDescription and travel. 2. Columbia River ValleyHistory.. 3. Columbia

River ValleyAntiquities. 4. Natural HistoryColumbia River Valley. 5. FossilsColumbia River

Valley. I. Title.

F853.N57 2003

979.7dc21

2003045609

Sasquatch Books

1904 Third Ave, Suite 710, Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 467-4300

www.sasquatchbooks.com

v3.1

A UTHOR S N OTE ON G EOGRAPHY AND L ANGUAGE:

In this book the Columbia Plateau refers to the part of the rivers drainage that lies between the Rocky Mountains and the Cascade Range. The Columbia Basin denotes the arid central portion of the Plateau. The Snake River is part of the larger Columbia drainage.

Ethnologists divide the native peoples of the Columbia drainage into three cultural groups. Plateau tribes inhabited most of the interior and spoke Kootenai, Interior Salish, or Sahaptin languages. Great Basin peoples, all Shoshoean speakers, were concentrated in the Snake River country. The Coastal cultures along the lower Columbia spoke Chinookan and Coast Salish languages.

Contents

THE COLUMBIA RIVER COUNTRY

Introduction

T HE MOMENT THE REAR WHEEL BROKE through the crust, I knew I was really stuck. Muttering curses, I switched off the engine and surveyed the situation. I had backed up too near a grove of birch trees that surrounded a seeping spring, and one wheel was buried to the hubcap. The slice of blue clay that had enveloped my tire emitted a whiff of indigo perfume, and when I bent to look I caught a glimpse of something long and smooth embedded in the mud. At first I took it for the leg bone of an animal, and struggled to pry it freeIve always loved to pick up bones and try to figure out what animal they belonged tobut the fragment proved to be nothing more than a plank from a farmers old spring box, warped to a pleasing arc by the preserving goo. Rubbing my fingers over the raised grain of the board, I figured that it must have been only a century or so since the birch spring homesteader had set the board in place.

Now the rut that had dragged down my car was offering a small relic from those days for my perusal. The spring where I was mired lay on an open bench, and I walked out to its edge and looked down on the Columbia River. From the site of my misfortune, the whole country was laid out for me to seeopen hillsides of ponderosa pine, new outcrops of colored dolomite, draws filled with darker Douglas firs and yellow-green tamarack. Time marched backward from the homestead spring, to the fur traders who had floated past, riding the initial wave of European contact, to the tribal memories buried beneath the waters. The round peaks to the north still capped with snow in early June hinted at the glaciers that had carved the bench where I stood.

The word relic conjures up a host of connotations, from human remains to a historic souvenir. It can denote a custom from the past, the remnants of an ancient language, or a fragment of a whole. It can represent the last of a dying species, or an indefatigable survivor. During the years I have lived in the Columbia country, I have come to see its vast natural and human archives as a reliquary of its former lives, a reservoir of clues that connect this moment to the distant past, this place to territories far away.

That is where this book begins, with the discovery of such relics. Some of them fit comfortably in a pocket; some are far too large for transport. Certain ones have mesmerized generations of chroniclers and invited intense scientific scrutiny, while others have barely been noticed. Many take the tangible form of rock or bone; others are as ephemeral as the faint whiff of a bloom in spring or the laugh of an auntie poking fun. Some have faded to extinction; others can be found by any kid with a penchant for muddy feet. But whatever form they take, each evokes a facet of the regions past, reminding us that this place has not always been as we see it now. Their voices call across time, carrying snatches of the big rivers long and larger song.

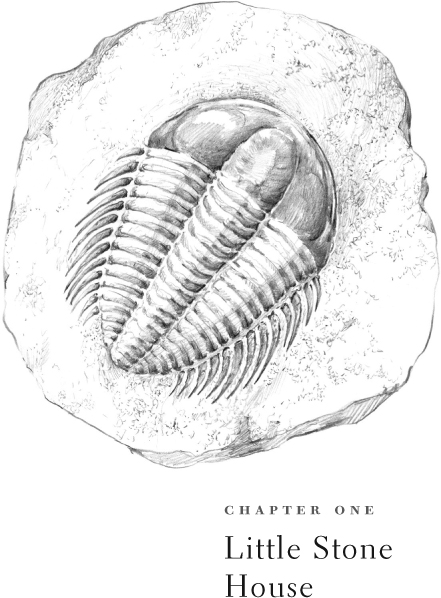

Upper Cambrian trilobite (Labiostria westropi) from Tanglefoot Creek

Tanglefoot

L OOK FOR COOKIES , Rolf had said, as he directed my attention to a tiny squiggle on a map of southeastern British Columbia. Little round treats in the streambed. He made it sound so easy.

By the time I reached Tanglefoot Creek on the west slope of the Rockies, I was beginning to wish I had waited until after spring runoff. Rising temperatures had loosened the snowpack from the nearby peaks, and the world seemed to be collapsing all around. A grinding porridge of mud and gravel sluiced bushes from steep rock faces. The creek, milky green in color, snapped like a racer snake, carrying chunks of my trail headlong toward the sea.

When I paused to check my progress, heavy drops of rain spanked down on my scrawled directions. I turned up a side rivulet that careened through a tight canyon, picking my way across a fresh mudslide. Clumps of saxifrage flowers, white stars touched with maroon and lemon spots, surfed atop thin plates of brown shale. Outcrops of the same shale shot steeply upward on either side of the creek; this was country that had been bent and twisted on a grand scale. Each step forward in space moved me backward in time.

The narrowing canyon finally forced me into the stream. I swapped boots for water sandals and plunged into the torrent. The water was so cold that I had to hop onto a boulder every few minutes to let the sting go out of my feet. Grabbing at gooseberry bushes to steady myself, I cast my eyes left and right to match the pace of the torrid runoff, searching for the remains of a creature long extinct. The first round stone I picked up turned out to be completely smooth. So did the next several dozen. A thrushs song ascended leisurely over the creeks icy roar, and a succession of hard showers rode in one upon the next. The bird sang many times before an emerging ray of sunlight caught the raised edge of a biscuit-shaped rock on the nose of a gravel bar. I bent down and wrapped my hand around it, feeling for ridges. Even before I lifted it free of the creek, my fingers told me I had found a trilobite.