Contents

Guide

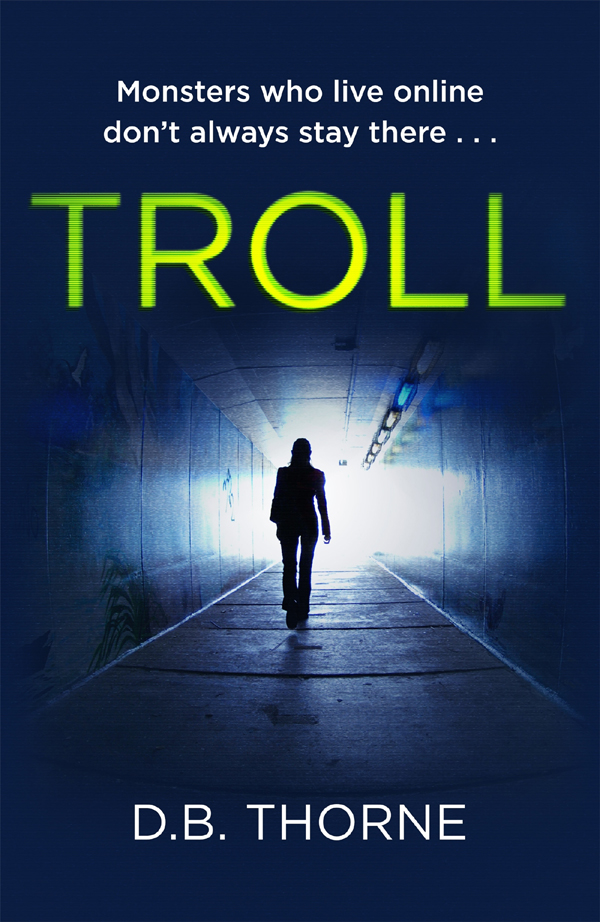

TROLL

D.B. Thorne has worked as a writer for the last 15 years, originally in advertising, then in television and radio comedy. He has written material for many comedians, including Jimmy Carr, Alan Carr, David Mitchell and Bob Mortimer. He was a major contributor to the BAFTA-winning Armstrong and Miller Show, and has worked on shows including Facejacker, Harry and Paul and Alan Carr: Chatty Man. Troll is his fourth novel.

Also by D.B. Thorne

East of Innocence

Nothing Sacred

Promises of Blood

TROLL

D.B. THORNE

Published in trade paperback and e-book in Great Britain in 2017

by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright D.B. Thorne, 2017

The moral right of D.B. Thorne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the authors imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 594 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 595 9

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

one

FORTUNE LOOKED AT THE MAN IN CHARGE OF FINDING HIS missing daughter with the kind of dismay he generally reserved for the most dismally incompetent interview candidates. This was the man responsible for piecing together her final movements? Chasing down leads and taking names? Overweight, crumpled, he had the look of somebody whod suddenly found himself in charge of his own washing and ironing. In his recent past, Fortune guessed, was a failed marriage and a whole lot of takeaways.

Looking at him over the interview room table, Fortune had a feeling close to panic. He blinked and said, Im sorry?

Scaled it back, said Marsh. He had little eyes and they werent looking at Fortune; were looking anywhere but. No choice.

But shes still missing, said Fortune.

Marsh nodded. I know. Im sorry. But its been weeks, and theres still no He stopped. Body, thought Fortune. You mean body, but you havent got the guts to say it. Marsh coughed. Were not closing the investigation. Just reclassifying it.

Reclassifying it, repeated Fortune. What does that even mean? It sounded to him like the kind of empty phrase his younger staff used: moving the needle, taking it offline, reaching out. Air, nothing more. It didnt make sense.

Mr Fortune, Marsh said. Youre upset. Its understandable.

Of course its understandable, said Fortune. Shes my daughter. Shes disappeared off the face of the earth. And youve got no leads, no ideas, no nothing. And now youre giving up? He tried, but he couldnt quite keep the desperation out of his voice.

Not giving up. Re

Reclassifying. I heard. I still dont know what it means.

It means Marsh sighed. Mr Fortune, were trying to find your daughter.

Not very hard.

As hard as resources will allow.

How many resources does a missing girl merit? said Fortune. How important is her life? Ten policemen? Four? One?

Marsh sat back in his chair, massaged the bridge of his nose. He had thin hair, grey. He couldnt be in charge, running the show, thought Fortune. His daughter deserved better.

Mr Fortune, weve done what we can. Thrown bodies at the investigation, set up an incident room, knocked on doors, interviewed friends, ex-boyfriends, colleagues. Weve spoken to the press, put out an appeal. CCTV, the lot. He lifted his shoulders. Nothing. At this point, theres just not much more we can do. Without Again he didnt say the word. Body. Without the body of my only child, my daughter. Sophie.

You cant give up on her, said Fortune.

Were not giving up. Were scaling back. No choice.

How many people have you got on it? Right now?

Marsh picked up a pen, something to look at rather than Fortune. Right now, Mr Fortune, we have one officer continuing with enquiries. The investigation isnt closed. But, like I say, its been scaled back.

One. One officer. Fortune closed his eyes for several seconds. He had come a long way. Taken time off. What can one officer do? Shes out there somewhere, and she needs help. He could hear a pleading tone in his voice, imploring. God, but he sounded desperate.

Mr Fortune, said Marsh, what do you think happened to your daughter?

Thats why Im here, said Fortune. To find out.

No. I mean, when you heard that she had gone missing, what was your immediate thought?

Fortune shook his head. I dont know. That shed I dont know.

That shed what? said Marsh.

Fortune shrugged, trying to keep calm. Gone on holiday. Run off with a new boyfriend. I dont know. Couldve been anything.

Marsh nodded, leant back in his chair. They sat facing each other and Fortune could hear the hum of the air conditioner, hum and rattle, a world away from the sleek, smooth hiss of his Dubai office.

There was a knock on the door and a young woman came in with two coffees, put them on the table. Marsh nodded to her and she left, closed the door with a gentle click. He lifted one of the Styrofoam cups, took a drink, made a face. He put the cup down carefully, slowly.

How many times did your daughter attempt suicide?

There it was. The question Fortune had been expecting, waiting for. The question he didnt want to face. He remembered hospital corridors, hard seats, his wife next to him, the click of heels on linoleum. The slow tick of a wall clock, more than one clock, more than one hospital.

No, he said. No.

Were not ruling anything out, said Marsh. But given her history

Fortune wished Marsh had the courage to finish his sentences. To tell it like it was. That his daughter had had a troubled adolescence, all the way through her late teens and early twenties; that she had been moody, anxious, depressed, angry. Lost.

Shed been better, he said. Much better. A different person.

No more suicide attempts. No more pills, flatmates finding her after coming back from a late bar shift. No more ambulances, vigils, apologies, tears. She had been better, making a life for herself, or at least that was what hed been told.

Marsh sighed and opened a file that he had brought with him, placed it on the table between them. It was beige and thin. If this was it, Fortune thought, the sum total of the investigation, then a lot of midnight oil had gone unburned. Marsh took out a clear plastic wallet with a piece of paper inside, using two fingers to slide it into place between the pair of them.

We found this, he said, turning it so that Fortune could read. An A4 sheet of paper, covered in scribbles. Fragments of phrases in black pen, haphazardly placed. This needs to end, underlined many times. This ends today, the words gone over again and again so that the ink shone and the paper was indented, almost worn through.