Supernormal Stimuli

How Primal Urges Overran

Their Evolutionary Purpose

Deirdre Barrett

W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

Copyright 2010 by Deirdre Barrett

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barrett, Deirdre.

Supernormal stimuli : how primal urges overran their evolutionary purpose / Deirdre Barrett.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-393-06848-1

1. Evolutionary psychology. 2. Behavior evolution. I. Title.

BF698.95.B36 2010

155.7dc22

2009037078

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Contents

Supernormal Stimuli

What Are Supernormal Stimuli?

T he European Cuckoo, whose distinctive call issues from our cuckoo clocks, seems more goofy than sinister. However, this creature is the leading example of a brood parasite. A female cuckoo will sneak into the nest of another species when the parent bird is away and lay an egg, shoving a rightful one out so the count will be correct. She flies away to repeat this in other nests, leaving the care of her progeny to the unsuspecting adoptive parents.

The cuckoo egg resembles those of the host but its often a bit larger or brighter. The nests owner sits on the cuckoo eggs preferentially if there are too many to keep warm. When the baby cuckoo hatches, its beak is wider and redder than the other chicks. If there are any other chicks . The mother cuckoo has already dumped one egg, and the baby cuckoo tries to push remaining eggs or newly hatched siblings to their death. The cuckoo enacts the Cinderella story in reverse: the stepmother gives Cinderella all the attention while her ugly stepsisters go wanting.

Baby cuckoo fed by foster parent.

Tragicomic dramas play out in every arena of animal life. Put a mirror on the side of a beta fighting fishs aquarium and the gaudy iridescent male will beat himself against the glass attacking a perceived intruder. A hen lays eggs day after day as a farmer removes them for human breakfasts30,000 in a lifetime. Not a single chick hatches but she never gives up try

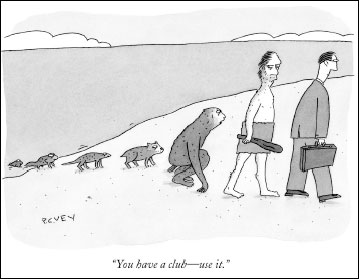

These animal behaviors look funny to usor sadthe reflexive instincts of dumb animals. But then theres a jolt of recognition: just how different are our endless wars, our modern health woes, our romantic and sexual posturing?

Human instincts were designed for hunting and gathering on the savannahs of Africa 10,000 years ago. Our present world is incompatible with these instincts because of radical increases in population densities, technological inventions, and pollution. Evolutions inability to keep pace with such rapid change plays a role in most modern problems.

Animal biology developed a concept that is crucial to understanding the problems instincts create when disconnected from their natural environmentthat of the supernormal stimulus . Nobel laureate Niko Tinbergen coined this term after his animal research revealed that experimenters could create phony targets that appealed to instincts more than the original objects for which theyd evolved. He studied birds that lay small, pale blue eggs speckled with gray and found they preferred to sit on giant, bright blue ones with black polka dots. The essence of the supernormal stimulus is that the exaggerated imitation can exert a stronger pull than the real thing.

Supernormal stimuli explain why other birds give the baby cuckoo more attention than their own young; why the unyielding, invulnerable fish in the mirror provokes such a violent attack; why the faux-feathered lothario gets all the girls.

Many evolutionary concepts have been applied to human behavior by biologists. Some have crossed over into popular conversation. However, the importance of supernormal stimuli has not yet been fully appreciated in either arenauntil now. In the pages that follow, I appropriate the term to explain a broad array of human folly.

Animals encounter supernormal stimuli mostly when experimenters build them. We humans can produce our own: candy sweeter than any fruit, stuffed animals with eyes wider than any baby, pornography, propaganda about menacing enemies. Instincts arose to call attention to rare necessities; now we let them dictate the manufacture of useless attention-grabbers. My last book, Waistland , explored how supernormal food stimuli have produced our obesity crisis. The present book applies the concept to sex, health, international relations, and media. I also draw on other ideas from animal ethology and evolutionary psychology that further illuminate the disconnection of instincts from their natural environment.

Its not all bad news. Once we recognize how supernormal stimuli operate, we can craft new approaches to modern predicaments. Humans have one stupendous advantage over other animalsa giant brain capable of overriding simpler instincts when they lead us astray. This book emphasizes the importance of recognizing when we need to push the override button.

Chapters 3 through 8 each examine a particular modern problem. But first, Chapter 2 describes how Tinbergen discovered supernormal stimuli and related concepts. I devote significant space to this mans quirky life story because his distinctive personality, his extraordinary family, and the events of World War II all contributed to why he was able to step outside the perspective of his cultureand at times his speciesto examine human instincts and behaviors with such remarkable objectivity. Chapter 2 concludes with a summary of how ethology, evolutionary anthropology, and psychology have built on Tinbergens insights in the years since.

Making the Ordinary Seem Strange

B orn in 1907 in The Hague, Niko Tinbergen grew up as the second of five in a family that would produce what none other has before or since: two Nobel Prizewinning siblings. Tinbergens parents were both schoolteachers. They showered praise on studious oldest brother Jan, while Niko considered his youngest brother, Luuk, the brightest in the family. As a middle child, Niko only just scraped through, with as little effort as I judged possible without failing.

The main biography of Tinbergen, written by his former graduate student, Hans Krunk, is strongest in describing how his scientific theories developed. so profound that some didnt speak to others for decades or why they ignored major depressions among their members and even the eventual suicide of one.

More is known about Tinbergens early passion for watching fish and fowl. In a pond in the Tinbergen backyard, Niko could observe stickleback fish, frogs, and waterbirds. He roamed nearby woods and beaches, sometimes with little brother Luuk in tow, finding more exotic wildlife.

Niko joined the Nederlandse Jeugdbod voor Natuurstudie (NJN; roughly translated as the Dutch Youth for Nature Studies). This club organized hikes and summer campslike the Boy Scouts, except members were of both genders aged 1223, and there was no adult supervision. Boys and girls mixed freelyhighly unusual, even as late as the 1950s, but anything sexual was frowned upon, a fellow NJNer recalls. We were very chaste, and established couples were not expected to even hold hands in company.