SHAPESHIFTERS

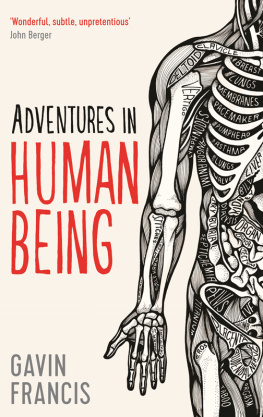

Gavin Francis is a doctor and writer. He is the author of Adventures in Human Being, which won Saltire Non-Fiction Book of the Year, as well as True North and Empire Antarctica, which won the Scottish Book of the Year Award and was shortlisted for the Ondaatje Prize and Costa Prize. He also writes for the Guardian, The Times, London Review of Books and Granta. He lives and practises medicine in Edinburgh, where hes a member of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine and a Fellow of the Royal College of General Practitioners.

ALSO BY GAVIN FRANCIS

True North: Travels in Arctic Europe

Empire Antarctica: Ice, Silence and Emperor Penguins

Adventures in Human Being

WELLCOME COLLECTION is a free museum and library that aims to challenge how we think and feel about health. Inspired by the medical objects and curiosities collected by Henry Wellcome, it connects science, medicine, life and art. Wellcome Collection exhibitions, events and books explore a diverse range of subjects, including consciousness, forensic medicine, emotions, sexology, identity and death.

Wellcome Collection is part of Wellcome, a global charitable foundation that exists to improve health for everyone by helping great ideas to thrive, funding over 14,000 researchers and projects in more than seventy countries.

wellcomecollection.org

SHAPESHIFTERS

On Medicine & Human Change

GAVIN FRANCIS

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

wc1x 9hd

www.profilebooks.com

Published in association with Wellcome Collection

183 Euston Road

London nw1 2BE

www.wellcomecollection.org

Copyright Gavin Francis, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 323 9

For lifes optimists,

who see hope in human change

LECTOR INTENDE, LAETABERIS

Mankind

N. human race, human species, human kind, human nature; humanity. human being; person, individual, mortal, body.

Adj. human, mortal, personal, individual, social.

Change

N. alteration, mutation, variation, modification, metastasis, deviation, turn, evolution, revolution,

transformation, transfiguration; metamorphosis.

V. alter, vary; modulate, turn, shift, veer, shuffle, swerve, deviate.

transform, transfigure, metamorphose.

My aim is to sing of the ways bodies change, ceaselessly transforming into other forms.

Ovid, Metamorphoses (c. 8 CE)

All things change with time, and we change with them.

Lothar, Holy Roman Emperor (c. 840)

And then I, a woman, by a flick of Fortunes hand was transformed into a man.

Christine de Pizan, The Mutation of Fortune (1403)

We are nothing but a bundle or collection of different sensations and are in a perpetual flux and movement.

David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature (1739)

It is itself unchanged, the same water which my youthful eyes fell on; all the change is in me.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854)

Metamorphosis governs natural phenomena reflects the shifting character of knowledge and attitudes to the human.

Marina Warner, Ovidian Metamorphosis in Contemporary Art (2009)

Contents

A note on confidentiality

THIS BOOK IS A SERIES OF STORIES about medicine and the changing human body. Just as physicians must honour the privileged access they have to our bodies, they must honour the trust with which we share our stories. Even as long as two and a half thousand years ago that obligation was recognised: the Hippocratic Oath insists whatsoever in the course of practice you see or hear that ought never to be published abroad, you will not divulge. As a doctor who is also a writer Ive spent a great deal of time deliberating over that use of ought, considering what can and cannot be said without betraying the confidence of my patients.

The reflections that follow are all grounded in events within my clinical experience, but the patients in them have been so disguised as to be unrecognisable any similarities that remain are coincidental. Protecting confidences is an essential part of what I do: confidence means with faith we are all patients sooner or later; we all want faith that well be heard, and that our privacy will be respected.

1

Transformation

From so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

THERES A PARK near my medical office lined with cherry trees and elms that undergo beautiful annual transformations. If theres time on my commute Ill stop at a bench and watch them for a few moments. Winter brings storms, and the last few years have seen several of the tallest elms blown over. When they fall down, tearing up their roots, deep coffin-sized gashes open in the earth. Around Easter the branches thicken with a green so enchanting I see why some imagine it as the colour of heaven. The blossoming of the cherry trees in spring strews the grass with petals, and to take a stroll beneath their branches is to be fted in pink. The summer air feels ripe and dense barbecues are lit and babies play on rugs in the shade; acrobats teeter over ropes strung between the tree trunks. But my favourite season is autumn, when the sky feels high, the air pellucid and brittle, and heaps of crimson, auburn and gold gather around my feet. Ive been appreciating this park for around twenty-five years its adjacent to the medical school where I trained.

Aged eighteen, in the first year of training, I walked through drifts of those leaves to a biochemistry class that Ive never forgotten a lecture where I had something approaching a revelation of the intricacy, the interconnectedness, even the wonder of life. It had an inauspicious beginning: projected on the wall was a complex diagram of the haemoglobin molecule. The tutor explained that the chemical which binds oxygen into red blood cells, known as a porphyrin ring, was essential both to the haemoglobin of blood and the chlorophyll that traps the suns energy in leaves. Thanks to porphyrins, she said, life on earth as we know it is possible. Up on the wall, the molecular structure resembled a four-leafed clover, with porphyrin leaves interlocked in an architecture of almost Gothic complexity. Cradled at the core of each of the four leaves was a lava-red atom of iron.

When oxygen binds to the heart of each leaf, she explained, it reddens like an autumn maple; when oxygen is released, it darkens to purple. So far, so biochemical. But this isnt a static process, the tutor added, its dynamic and alive. The binding of oxygen transforms its cradle; the stress of that transformation pulls a tiny atomic lever which bends the cradles of the other three, encouraging the take-up of more oxygen. This was the first revelation of the elegance of biochemistry, as startling as it should have been obvious: from chlorophyll to haemoglobin, molecules cooperate with one another in order to sustain life.