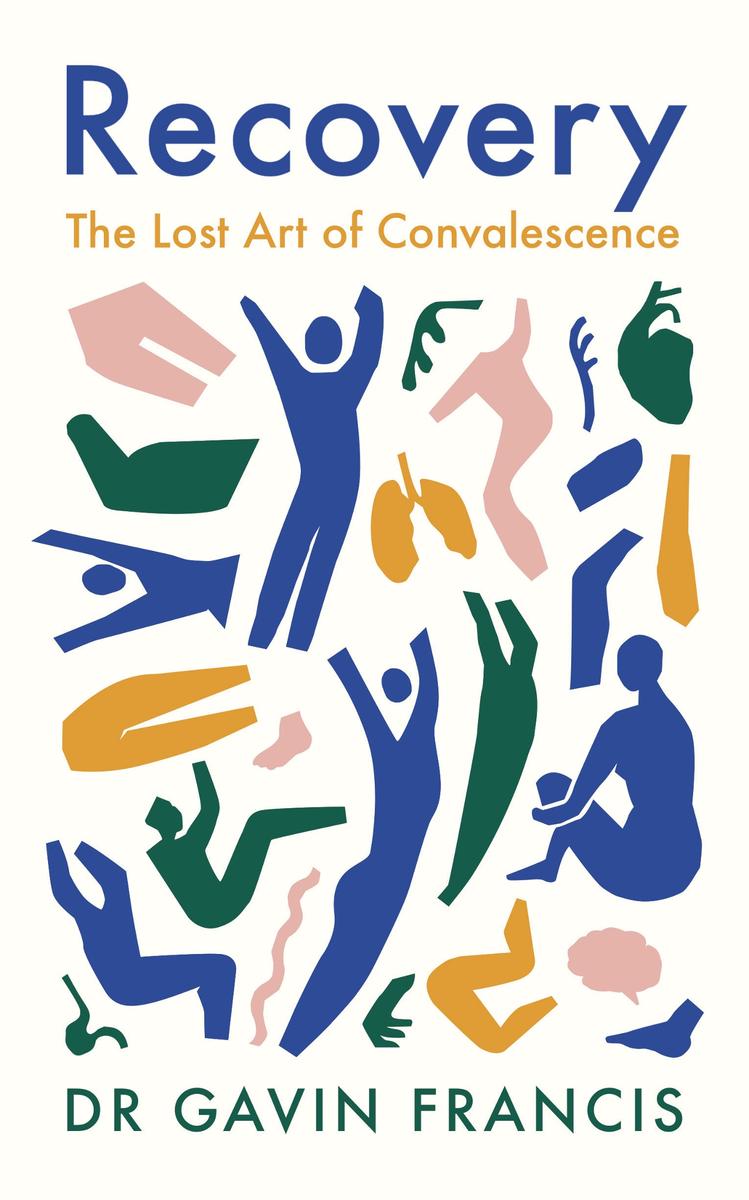

Gavin Francis - Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence

Here you can read online Gavin Francis - Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Wellcome Collection, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence

- Author:

- Publisher:Wellcome Collection

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

v

For my teachers

(in other words, my patients)

vi

vii

I enjoy convalescence. It is the part

that makes the illness worthwhile.

G. B. Shaw viii

This is a book about illness and recovery, about healing and convalescence. Im a general practitioner trained in a Western medical view of the body, and the reflections that follow are grounded in that tradition. Illness is as much about culture as it is about disease, and our ideas and expectations of the body profoundly influence the ways in which we fall ill. They also influence our paths towards recovery. A Faroese farmer, a Thai engineer, a Peruvian taxi-driver and a Sudanese schoolteacher will all have different traditions of the body and of health, and their paths to recovery can be comparably diverse.

What follows is a series of explorations of recovery and convalescence seen from within xii a particular medical tradition my own as a European, twenty-first-century, general medical practitioner. While I acknowledge the value and the virtues of alternative approaches to the body and to illness, I will leave discussion of them to others trained in their use.

The patient stories that follow are either so commonly encountered as to risk no betrayal of confidence, or have been disguised beyond any possibility of recognition. Confidence means with faith we are all patients sooner or later; we all want faith that well be heard, and that our privacy will be respected.

When I was twelve years old I had a stupid accident. I was cycling home from town with friends when a colossus of a lorry passed too close, causing me to swerve my bicycle. It was over in a moment: I put out my left foot to steady myself, and my heel jarred hard against the kerb. The impact tumbled me off the bike and onto the pavement where I lay in the dust, relieved to be alive, but unable to straighten my leg. The lorry didnt stop.

My pals pedalled off to get help, and after what seemed an age, but was probably only twenty minutes, my mum turned up to take me to hospital. An X-ray showed that the topmost piece of my shin bone, the tibial plateau, had splintered, and a fragment had become lodged at the back of my knee joint. And just as a sliver of wood can hold back a heavy door, that tiny fragment wedged my knee in a bent position.

I was taken to an operating theatre where, under anaesthetic, a surgeon wrenched the knee back and forth until that splinter of bone fell into place. A cylinder of plaster was rolled around the leg, I was given some crutches, and told to come back in the autumn.

To be immobilised in plaster through the summer holidays would have its challenges for any twelve-year-old, but it was once the plaster was removed that my journey of recovery really began. A metamorphosis had occurred. The knee had become bulbous, and my thigh and calf seemed by comparison sticklike, wasted and malnourished. A fine pelage of hair had sprouted under the protection of the plaster, bizarrely dark against skin that was now as white as bone. When I tried to walk, the knee wobbled and gave way.

It took months for my leg to feel like my own again; months of boring, punishing exercises to build up the muscle. Relearning to walk was a process led not by doctors, but by a pair of brisk and cheerful physiotherapists whose department I remember as one of too-bright lights, wipe-clean benches, weights, straps and gym bars on the walls. I can recall the distinctive disinfectant smell of the floor cleaner, and the regular company of a man Id met previously on the ward who had shattered his leg in a motorbike crash. He was big, with a black moustache and stubble, and with a delicate gold hoop that hung from one of his earlobes. As we groaned and sweated together, lifting weights attached to our ankles, he joked about how I was recovering more quickly than him.

When I think of that period of convalescence now I remember afternoons at home reading in the sunshine, and doing my physiotherapy exercises at first tentatively, then with more confidence. The days were busy with sounds: of birds in the garden, cars in the distance, wind moving through the barley of the field behind the house. For twelve years my body had rarely stopped, and it seemed unnatural to have it rendered so motionless, as if with my injury the nature of time itself had warped and transformed. The flow of my life had been stilled, but it was that very stillness that gave me the opportunity to heal.

It wasnt my first experience of convalescence. A couple of years earlier I had woken one morning with a hammer-blow headache and a churning in my stomach. I suddenly knew the truth of the saying he couldnt lift his head off the pillow. My GP was called for, a kindly man of the old school who took one look and, suspecting meningitis, sent me urgently to an infectious diseases hospital an hours drive away, where the diagnosis was confirmed. I spent eight days and nights in that hospital, in a room with large windows that gave on to trees and afternoon sunshine.

In the niches of my memory I carry no images of the doctors, only one of a nurse in a sky-blue tunic, her black hair in a bun, her kind face lined with smiles. An iron-framed bedstead, glaring white sheets, and again, that smell of floor disinfectant. A window in an internal wall of the sick room gave on to a nurses station even when my parents were away I was kept under surveillance. Though my mum and dad took shifts to be with me for most of the day they also had my brother to attend to, and I spent many hours alone in silence waiting for them to come; waiting for home.

With a limb it seemed possible to objectify the part that needed recovery, to look down on the leg and say thats the problem, right there. Working to build up the leg was effortful but also visual, my progress inscribed in the bulk of my thigh, the colour of my skin, the comparison with the healthy leg at its side. My recovery from meningitis was far more difficult to grasp, the edges of what recovery meant were far less clear. A languorous fuzzy-headed exhaustion dominated my days, burnishing the world with the bright haze of a dream or a hallucination. My body was in convalescence, but the process itself felt disembodied, ethereal, as much mental as physical. As I look back on it now, its clear that it was my first experience of the complexities of convalescence, and how it can and must take very different forms with different illnesses, and between different people.

Six years after my leg recovered I went to medical school to train to be a doctor. A decade after that I was working in a brain injury unit, as a junior member of a team caring for a relentless flow of broken people mostly young men who had been injured through reckless driving, falls or fights. I saw how quickly their bones could heal, but how much longer it took for their brains to do the same. Once the initial crisis of injury was over blood clots removed, pressure relieved, skulls plated and wired they would be moved to a rehab ward where they might stay for months at a time, gradually relearning what were known as ADLs activities of daily living: bathing, dressing, cooking and so on. For some, those ADLs would include relearning to walk or to talk.

The word rehabilitation comes from the Latin habilis, to make fit, and carries the sense of restoration: to stand, make, or be firm again. The aim of rehabilitation, then, was to make someone as fit as they can be, to be able to stand firmly on their own two feet. And though recovery was the clinicians ultimate aim, its curious that the words recovery and convalescence are generally absent from the index of medical textbooks. As long ago as the 1920s, in her essay On Being Ill, Virginia Woolf wrote that we lack a mode of writing about illness, that it is strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love, battle, and jealousy among the prime themes of literature. A century on, her assertion no longer holds true: we do have a literature of illness. But Id argue that we still lack a literature of recovery.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence»

Look at similar books to Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.