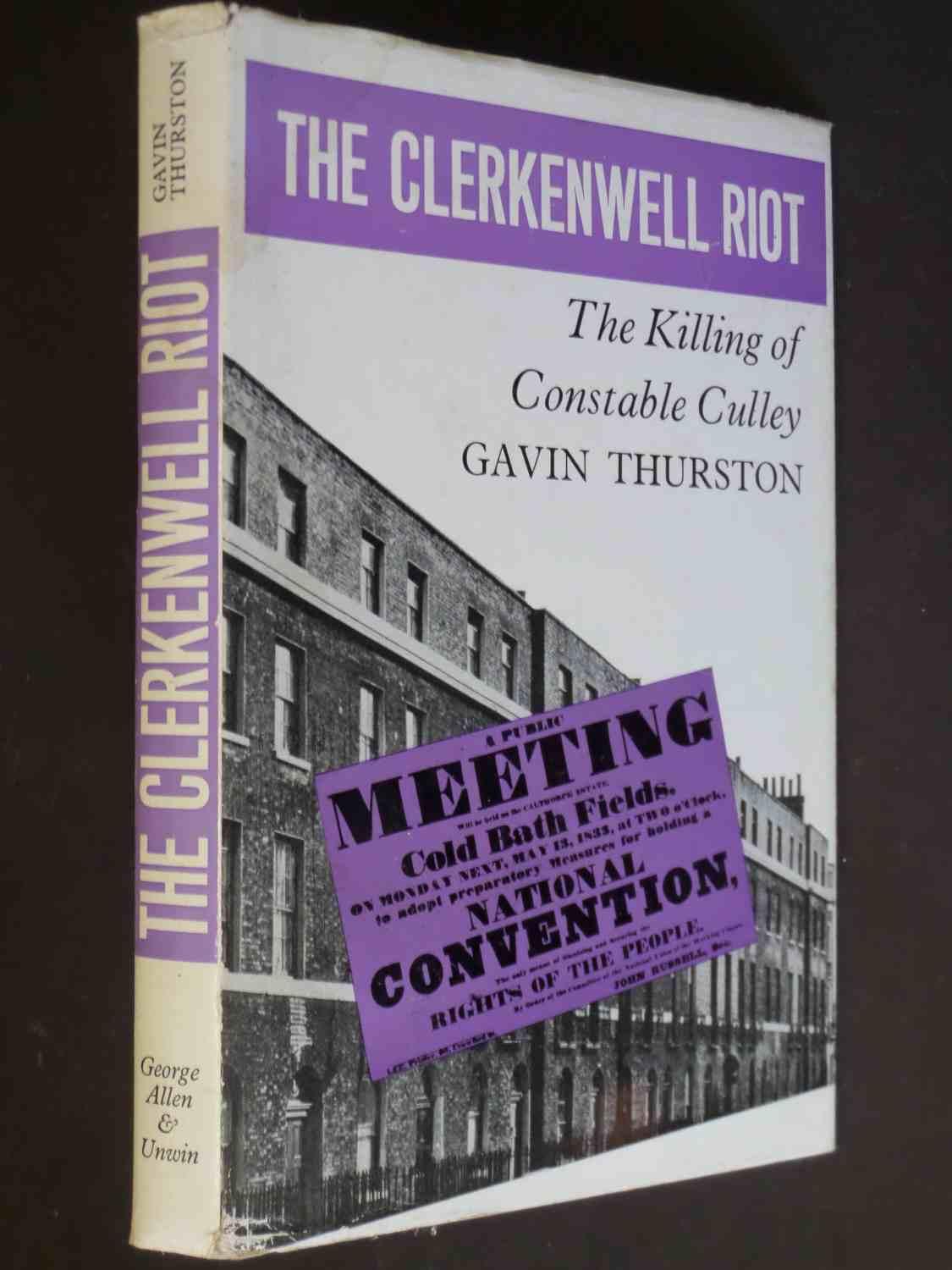

First published in 1967 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2022

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1967 George Allen & Unwin Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-03-203038-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-00-319086-8 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-03-203077-7 (Volume 3) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-03-203078-4 (Volume 3) (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-00-318657-1 (Volume 3) (ebk)

DOI: 10.4324/9781003186571

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN I967

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of

private study, research, criticism or review, as

permitted under the Copyright Act, 1936, no

portion may be reproduced by any process without

written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to

the publisher

George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1967

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

in 11 on 12 point Plantin type

BY C. TINLING AND CO. LTD

LIVERPOOL, LONDON AND PRESCOT

To My Friends in

the Metropolitan Police

Human beings, particularly in cities, have often reacted to adversity by rioting. Scenes of arson and violence in various parts of the world are frequently on our television screens, and we are sickened by the uniformly brutal methods of mob control. Large-rumped policemen, heavily armed, lay about them with staves; missiles fly through the air and, sometimes, a blood-dappled corpse is glimpsed lying among the debris. And so it has always been.

This is the story of a small riot. It happened in London, off the Grays Inn Road, 130 years ago. It was midway in time between the Peterloo massacre and the Chartist riots of the forties and was brought about by similar pressures; the struggle of the have-nots against the haves, with the desire for more say in the countrys affairs as the immediate issue. At the time the affair and its repercussions were hotly discussed for weeks. To-day, with the exception of one or two senior police officers, nobody to whom I have spoken had heard of the Cold Bath Fields.

Although the riot lasted only about ten minutes it was attended by the usual social stresses and familiar characters played their parts. But there were unusual features, there was no incendiarism and no pillaging and no member of the public was seriously injured. On the other hand one police officer was killed and two were seriously wounded. It was the first time that the Metropolitan Police had confronted a mob and quelled a civil disturbance armed only with batons, without military aid.

It is a strange but genuine tribute that we take our Metropolitan Police for granted. Their demeanour and methods contrast sharply with those of the riot police of other countries. The recent shooting in London of dure police officers while on duty evoked nation-wide shock and universal condemnation of the criminals. But it was not so in 1833 when Constable Robert Culley was stabbed to death at Cold Bath Fields. A jury found his killing justifiable, his funeral was desecrated by hostile crowds and storms of protest about police conduct raged in the Press and at public meetings. In their early years the police were hated; and it is to the credit of those responsible for their organization and training, for over a century, that the police attitude of steadfastness and tolerance is taken for granted. Colonel, later Sir Charles, Rowan and Richard Maynethe first Commissioners insisted on the highest standards of conduct which have never depreciated. Of course, we hear criticism of police behaviour from time to time, usually from those on the fringe of the criminal classes, sometimes from educated persons with a critical mentality. Comparison with the 1833 period will show how the relationship between police and public has improved although the contrary is often alleged.

The meeting at Cold Bath Fields was organized by a few obscure agitators for the purpose of forming a National Convention of the working classes, and was an early stirring towards the trades union movement. This half-baked affair attracted public notice and, as well as simple working folk, a number of known bad characters, some of them armed, turned up at the prospect of violence. Colonel Rowan was prepared for trouble and dealt with the gathering with precision and firmness.

In all discussions of politics, petitions to Parliament and the passing of triumphant resolutions it is essential never to forget that politics are about people and that life is a persons most precious possession. The centre of this account is the knife wound in Robert Culleys heart, and beside this all else fades into triviality. Could this wound be justified in any way?

On a warm day on the Calthorpe Estate one can almost feel the presence of the crowds : many of the houses are the same as they were in 1833 and the general conformation of the Cold Bath Fields can be made out. One can imagine the shouting and the brickbats and the hot angry faces; around the corner lies die horror of a warm corpse in a yard waiting to be carried upstairs to a small room.

Research is a frustrating procedure, clues lead to dead ends and records are silent on matters which one would expect to be fully documented. It would have been satisfying to trace the subsequent careers of many of those who will be mentioned. What happened to Mee, Stallwood and others? The Coroner, Thomas Stirling, is a shadowy figurehe was elderly at the time of the inquest and his name is not in the records of die Coroners Society of England and Wales, founded in 1846. There is plenty about the more distinguished figuresLord Melbourne, Peel, OConnell, Roebuck and Sir Charles Rowan himself, but we would dearly like to learn the fate of the humbler people.