Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

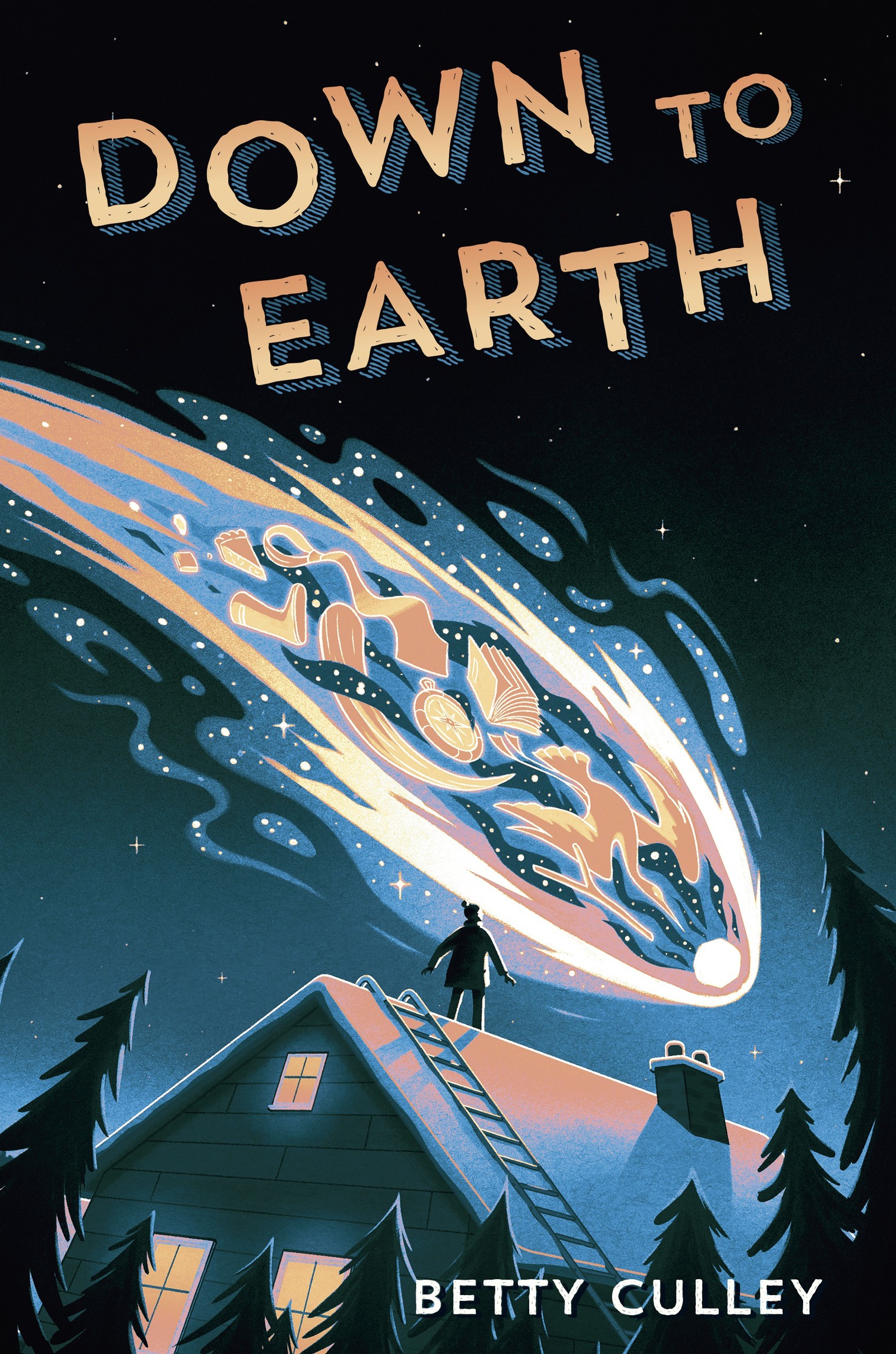

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright 2021 by Betty Culley

Cover art copyright 2021 by Robert Frank Hunter

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Crown and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Culley, Betty, author.

Title: Down to earth / Betty Culley.

Description: First edition. | New York: Crown Books for Young Readers, [2021] | Audience: Ages 8-12. | Audience: Grades 4-6. | Summary: Ten-year-old aspiring geologist Henry Bower investigates the meteorite that crash lands in the hayfield, discovering a rock that will change his family, his town, and even himself.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020050620 (print) | LCCN 2020050621 (ebook) | ISBN 978-0-593-17573-6 (hardcover) | ISBN 978-0-593-17574-3 (library binding) | ISBN 978-0-593-17575-0 (ebook)

Subjects: CYAC: MeteoritesFiction. | Family lifeFiction. | DowsingFiction. | ChangeFiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.C832 Dow 2021 (print) | LCC PZ7.1.C832 (ebook) | DDC [Fic]dc23

Ebook ISBN9780593175750

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

Penguin Random House LLC supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to publish books for every reader.

ep_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

Contents

FOR MY DAUGHTER, RACHEL

The pointed end of a forked stick is believed to point toward the ground when it passes over water.

The World Book Encyclopedia: Volume D

WHEN I WAS FIVE, I watched my father saw a Y-shaped twig off my great-grandfathers hundred-year-old apple tree. I waited to see if he would cut any other letters. There were branches that would make good Ls and Is and a curved J just right for my best friend, James. I wondered if Dad would saw off three branches and tie them together to make the H for my nameHenry.

Now Im one hundred percent older than I was then, and when Dad circles the tree his grandfather planted on Bower Hill Road, I know hes not looking for letters. Hes searching for the perfect forked stick for dowsing. He doesnt dowse for buried metal or gemstones. My dad, Harlan Bower, is a water dowser, and he uses his stick to find veins of water deep underground.

It doesnt have to be apple wood. It can be pear or willow. But if I ever try to dowse for real, I want my first branch to come from my great-grandfathers tree.

Having an H name like my father doesnt make me a dowser.

Being a Bower doesnt make me a dowser.

Living on Bower Hill Road, with its underground springs and good-tasting well water, doesnt make me a dowser.

My great-grandfather and grandfather could find fresh water trapped beneath hard granite rock.

Sixty-six-point-sixty-six percent of my grandfathers sons are dowsers.

My father: 33.33 percent

Uncle Lincoln: 33.33 percent

Uncle Braggy: 0 percent

My grandfather, my father, and Uncle Lincoln all discovered their water dowser talents when they were ten. I already read about dowsing in the D encyclopedia. It tells what it is, but not why some people can do it and other people cant.

My father taught me how to dig a hole with straight sides and how to put rubble rocks in the middle of my stone walls so they can shift with the frost.

But when I asked him how to dowse, he said its not something you can teach, it just happens.

I asked which was more important, the stick or the person that held it, and he said both.

I asked if it was easier to dowse for water on a rainy day, and he said hed never thought about that.

The apple tree has a black gash on the trunk where lightning hit it. No one saw the lightning strike, and the tree kept growing. No one teaches a tree to find water. Its taproot goes straight down into the earth, the same direction my fathers dowsing stick bends when it finds water.

The day I turned ten, I went up the hill and stood under my great-grandfathers tree. It was late August and there were so many apples they pulled the branches down around me. I touched the gash where lightning marked the tree. When I looked up, all I could see were Ys. Big Ys, little Ys, straight and crooked, too many to count. I traced the straightest Y with my finger, but I didnt break it off the tree.

This perfect Y is at the very end of a branch that grows toward Nanas front porch. It will be an easy one to find again if Dad asks me to dowse for a well. Then Ill finally learn whether my great-grandfathers abilities were passed down to me or not.

If I could have chosen to be a dowser for my tenth birthday present, I would have, but I know Dad would say its not something anyone else can give you.

Dowsing (water witching or water divining) is probably as old as mans need for water. It is an art certain people have which enables them to find underground sources of water.

Joseph Baum, The Beginners Handbookof Dowsing: The Ancient Art ofDivining Underground Water Sources

BEFORE WE HEAD OUT into the icy field, James breaks a branch off a wild cherry tree for his dowsing stick. I pull my little sister, Birdie, behind us on her red sled. Its so cold out the snow that falls is gritty like sand and wont stick. Its the kind my father calls dry snow.

James holds the Y-shaped branch the way my father and Uncle Lincoln do when they dowsepalms up, each hand holding an end of the V, elbows at his sides, the end of the Y pointing out in front of him.

What should I dowse for, Henry? James asks me. A mammoth tusk like the one we saw in the museum?

How about Dads good hammer? He lost it at the top of the field when he was fixing the tractor last summer.

Then Ill dowse in that direction. Jamess eyes are the clear blue of the sky reflected in the ice, and his blond hair sticks out from under his wool hat.

Keek keek keek. A small hawk glides overhead.

Keek keek, Birdie calls back. Birdie is only two, but she can make a cry just like a hawk.

Keek keek keek, the hawk screeches again, and flies off into the thick woods at the edge of the field.

I think I see something! James yells, running ahead with his branch. Look! A deer antler! My best find yet! He holds up the antler. I bet this would sell fast on the yard sale table.