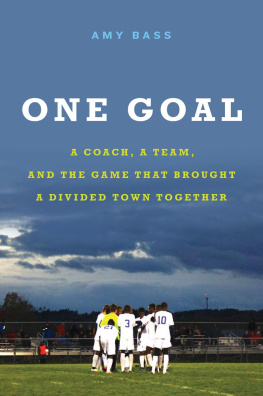

Cover copyright 2018 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBNs: 978-0-316-3964-7 (hardcover), 978-0-316-39657-8 (ebook), 978-0-316-51101-8 (large print)

For Sundus and Miles and Saaliha and my Hannah.

May they ensure the future welcomes all, everywhere, always.

When you have a football at your feet, you are free.

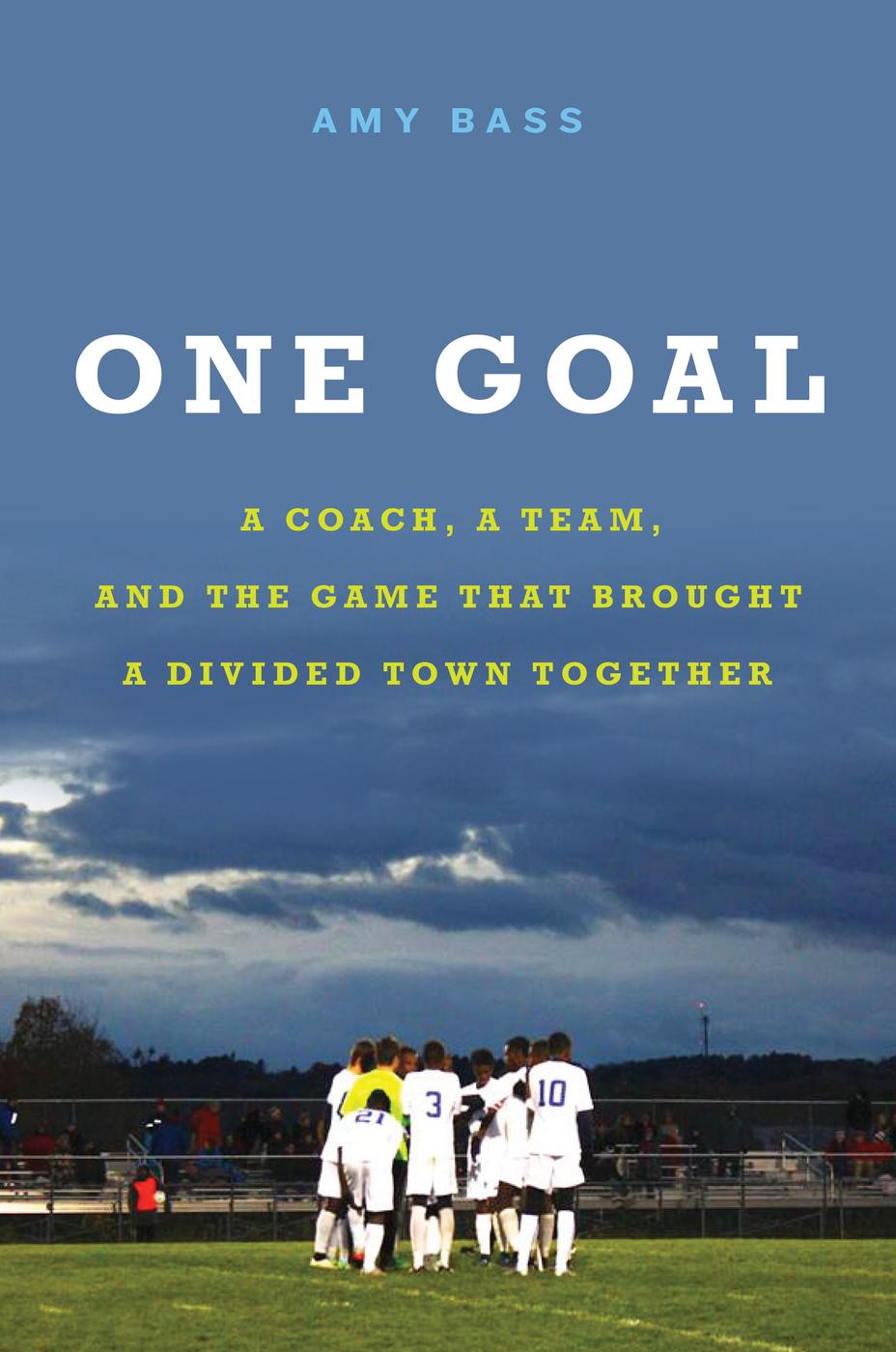

Master of the front handspring flip throw-in, Maulid Abdow held the ball and surveyed the vast field before him under the gray November sky. His teammates spread in a sea of blue across the green pitchKarim and Moha, Nuri and Q, Maslah and Abdi H. White-shirted Scarborough defenders multiplied by the second. Scarboroughs goalkeeper, Cameron Nigro, stood out among the scrambling traffic before the box, his black-and-gold adidas flame shirt mirroring his shocking blond Mohawk. He towered above the fray, a human roadblock before the net.

If Sid Vicious ever thought about playing soccer, he wouldve looked to Cam Nigro for style tips.

Maulid knew that his parents, Hassan Matan and Shafea Omarneither of whom spoke much English, but both could talk soccerwere somewhere in the stadium amidst the cacophony cheering the Lewiston Blue Devils. Women, heads covered by colorful hijabs, sat next to students with faces painted blue and white. Men in koofiyads cheered beside those in baseball caps and ski hats.

Some 4,500 fansthe highest attendance ever for a high school soccer game in Mainemade their presence known from the stands of Portlands Fitzpatrick Stadium on November 7, 2015. They gathered to watch the undefeated Blue Devils finish their season on top, which they had failed to do just one year ago against Cheverus High School. The 113 goals that brought them to this moment didnt matter anymore. Their national ranking didnt matter anymore. The goal they had scored earlier, the one a referee took awayoffside was the calldidnt matter anymore. All that mattered was this moment, this game, this team.

Maulid glanced at the clock: just over sixteen minutes remained. Funny and charming off the field, his deep voice often gently ribbing his friends before descending into rich laughter, he now stood deadly serious. His slim legs fidgeted back and forth, his hot-pink-and-blue cleats making dizzying patterns as his right foot pushed out in front, ready to take the lead.

Ohhhhhh, this isnt the jungle! he heard, followed by what he assumed were monkey noises. Stop flipping!

Maulid had no patience for racist trash talk, but Scarborough fans had a reputation. Thered been an incident about a year ago when Scarborough played Deering. But Coach drilled into them that putting points on the scoreboard was the best response, something he intended to do right now.

We play, Coach McGraw said in one of his legendary pre-game speeches, the right way. You rise above everybody else. We play hard. We play fair. Because winning without playing fair is a shallow victory. You let other people play those games. Those games take energy, energy that they waste.

Just beat em.

Everything the coach said corresponded to what Maulids parents told him about living in Maine: ignore ignorance. His parents were very happy to live in Lewiston. They appreciated the schools, health care, and jobs. Those things were important. But it was more than that. They felt free in Lewiston; something his mother had realized when she traveled back to Africa on a U.S. passport for the first time to see her family. Compared to what she saw there, she could never say that life in Lewiston was hard, no matter what it threw at her.

But it wasnt perfect. She understood that no matter how long they were in Maine, not everyone would be okay with it. Her kids told her about the stuff people wrote online, in response to the many newspaper articles over the years about Somalis living in Lewiston. She heard it herself when running errands or heading to her job at Walmart or to babysit. Why are you here? they asked, sometimes swearing. Why are you taking money from our government? Worry about yourself, she told her children. Yes, it hurts, but they cant hurt you. They have no authority to do anything to you.

On the field, Maulid heard it all, especially when the game turned rough, as it often did against Lewiston. Years ago, when he first came to America, he had no idea what kids were saying to him, but he knew it wasnt good. Now he understood those kinds of words all too well.

Get outta my side, nigger, a defender might taunt. Go back to your country.

I cant go back, Maulid says of such incidents, understanding that Lewiston is his home because it has to be. And if I could, they cant make me.

Ignore them, Maulid thought as Scarborough fans continued to bait him. He didnt have it as bad as Mohamed Moe Khalid, who played in the backline on this side. They were relentless to Moe, but he could take it. Moe played lacrosse in the spring and was no stranger to the n-word.

At least theyre watching, Maulid thought. He looked back at the bleachers and grinned just for the hell of it. They could say whatever they wanted. He wasnt going to stop.

He squeezed the white-and-black ball tighter, pressing it harder between his palms. It no longer felt slippery. He hoped a little spit on his dark fingers would be the magic glue that gave him the pinpoint precision he needed.

In a battle such as the one unfolding on the field, Maulid understood how a set piecea moment when the ball returns to play after a stoppage, usually by a corner kick, free kick, or throw-incould make all the difference. In the game against Bangor just a few days earlier, Maulid had made it happen. Indeed, he felt like hed done it a million times before, but every second of this game felt like the first. At the half, McGraw had emphasized they had to find one chance, one play, to get that one goal.

Lets see what kind of conditioning weve got, hed said to his huddling players as they bounced on their toes. Lets take advantage of the one break were going to get, and well see what well see.

Watching Maulid from the sidelines, Coach Mike McGraw knew all too well that the longer Scarborough held down his offense, the more one play could make the difference. They hadnt been held scoreless for an entire half all season. This was unfamiliar territory.

No, he assured anyone who asked. He didnt need a state title. He wanted one. More than anything. In the classroom, on the field, he was a patient man. But hed waited a long time for this chance. Thirty-three years, to be exact. One would be hard-pressed to find a more experienced high school soccer coach than McGraw, who first took Lewiston to a state soccer final in 1991. Then, his roster had names like Kevin and Steve, John and Tony. Now he coached Muktar, Maslah, Karim, and Abdi H. For many reasons, this was not the same team.