Contents

Guide

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this book contains names and images of people who have died.

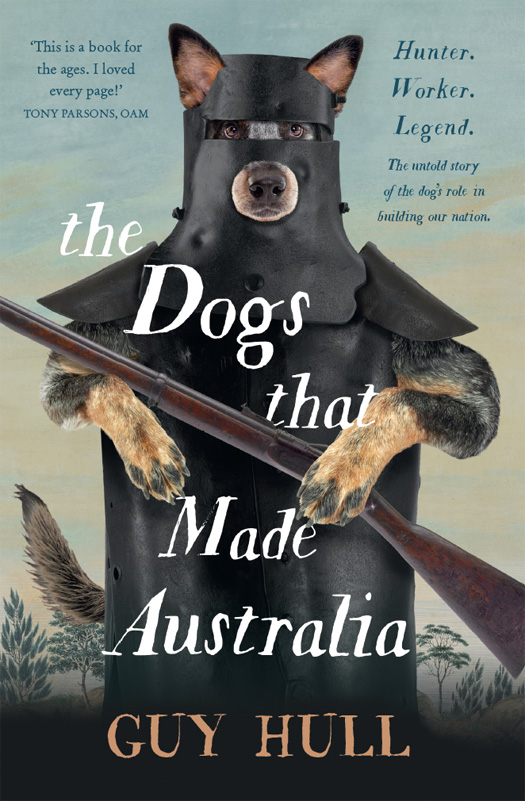

GUY HULL is a qualified and highly experienced dog behaviourist possessed of an encyclopaedic knowledge of dog breeds, cross-breeds and types, their histories and traits, as well as a passion for the historic and current role of the dog in Australian society. Based in New South Waless Snowy Mountains, Guy has managed dog shelters and worked as a council ranger, holds dog training classes and provides dog behavioural consultations.

HarperCollinsPublishers

First published in Australia in 2018

by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty Limited

ABN 36 009 913 517

harpercollins.com.au

Copyright Guy Hull 2018

The right of Guy Hull to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000.

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

HarperCollinsPublishers

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive, Rosedale 0632, Auckland, New Zealand

A 75, Sector 57, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201 301, India

1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF, United Kingdom

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower, 22 Adelaide Street West, 41st Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5H 4E3, Canada

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007, USA

ISBN 978 1 4607 5645 4 (paperback)

ISBN 978 1 4607 1044 9 (ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

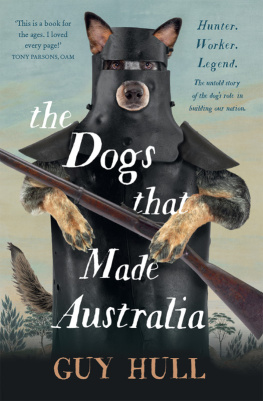

Cover design by Darren Holt, HarperCollins Design Studio

Front cover images: Armour [H20171] and Rifle [H2002.136] courtesy State Library of Victoria; dogs head by shutterstock.com; dogs paws by Agency Animal Picture / Getty Images; background painting courtesy State Library of New South Wales [972904]

For

Tony Parsons, OAM,

Bert Howard,

my sister, Vicki Hull,

and the dogs that busted themselves for Australia.

Read just about any account of the making of modern Australia, and you could be forgiven for thinking it was just the people who did all the heavy lifting. The true story of Australias pioneering dogs has never been told, and what most Australians believe to be the origins of our working dogs aint necessarily so.

Id owned Australian cattle dogs for over thirty years and, as my understanding of the breed increased, I came to reject their accepted origin as a dingo x collie. Theres plenty of dingo there all right, but the cattle dog has nothing of the collie about it. The more I looked at our cattle dog, and then kelpie origins, the more I realised to what extent wed all been dudded.

Then about eight years ago, I stumbled upon an article with a startling, bleedin obvious, and very plausible, explanation of the cattle dogs origins, and the seeds for this story were sown.

The author of that article, Albert (Bert) Howard, is a Second World War veteran who served in the Royal Australian Navy in the Pacific and was present at the Japanese surrender in 1945. In the 1980s he became heavily involved with the historical research for the privately published book Over-Halling the Colony, the story of the colonial beef cattle entrepreneur George Hall and his family. (Berts late wife, Beryl, was George Halls great-great-great-great-grand daughter.)

It was a Hall son, Thomas, who created the Halls heeler, the forebear of our cattle dogs, and Berts research included the Halls heeler as part of his decades-long family investigation.

Having sorted out the origins of the heelers, Bert turned his attention to our other great working breed wreathed in origin controversy, the kelpie. Noreen Clarks A Dog Called Blue and Tony Parsonss The Kelpie make use of Berts cold-case heeler and kelpie research.

Thanks to Bert Howard the whole story of Australias dogs can now be told. All the colonial heeler- and kelpie-related origin information herein, unless otherwise cited, is drawn from his Australian Origins & Heritage Files.

There is so little recorded about our early dogs (and nothing about the behaviour of prehistoric canines) that, where possible, I have elaborated on certain canine behaviours from a dog behaviourists perspective why wolves, dingoes or dogs acted in certain ways and what instinctive, human or environmental factors might have made them act so.

While I can manage the canine behaviour, it is beyond my powers to explain the behaviour of some of the humans instrumental in the founding of modern Australia. They have been roughed into the yarn with the measure of Australian levity that is their due. Some of the human cast even won supporting roles well done to them but when up against the dogs, most of the punters only auditioned well enough to land spots in the chorus line.

Our dogs are the real stars of this production, proving that eventually every dog, even a long-forgotten colonial dog, will have its day.

A ustralia was all grown up by 1901. Few Australians were old enough to remember convict chain gangs and British redcoats, and fewer still thought the wintry, grey confines of the United Kingdom a healthier or better place to live. That year, the six colonies New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia contrived to unite in nationhood. They had managed to gain independence from Britain without a single shot fired or a drop of blood spilled, gently wresting control of the asylum from the lunatics. It was very Australian in its doing.

The main driving forces behind Australias rapid rise to maturity had been gold and wool. But wool had been doing it tough for a few years.

From 1896 to 1902, eastern Australia laboured under the thrall of El Nios bone-dry misery, in what became known as the Federation Drought. It ravaged the continent with heatwaves, bushfires and dust storms, driving graziers to bankruptcy and decimating the nations merino flocks.

Yet in 1898, at the height of the crisis, Australias parched spirits had revived when a canine hero emerged, in an act that symbolised wools defiance of the droughts devastation.

On Saturday 2 July of that dry, dreary year, a man named Jack Quinn walked onto the Royal Agricultural Societys grounds at Moore Park in Sydney. He was there to take part in the sheepdog trial at the annual exhibition of the New South Wales Sheepbreeders Association. It was the biggest event of its kind in Australia, and the sheepdog trial, known as the Sydney Trial, was the most prestigious event on the national trials calendar.

Today was the second round of the competition. Beside Jack Quinn was his blue kelpie, Coil. He and Coil had travelled from Cootamundra in midwest New South Wales to compete.

As they moved to their starting position, a shocked silence settled over the uneasy spectators.

Thirty-one of Australias top working kelpies had run in the first round. Only eleven had progressed to the second and final run. In his first run, Coil had scored a perfect 100, and become the unbackable favourite to win the title. His faultless performance had been the first achieved in the three years of the Sydney Trials to that point.

Coil had all the right stuff: his mother, Gay, another Quinn kelpie, had won the inaugural event in 1896. Coil also had an inestimable advantage in his breeder and handler, the best kelpie man in Australia, and probably the greatest of all time.

Next page