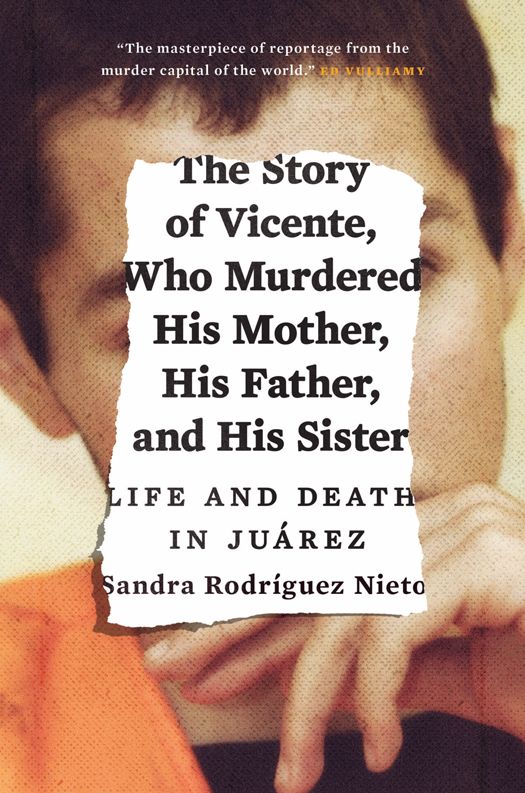

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PENs Writers in Translation programme supported by Bloomberg. English PEN exists to promote literature and its understanding, uphold writers freedoms around the world, campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and promote the friendly co-operation of writers and free exchange of ideas.

First published in the English language by Verso 2015

Translation Daniela Maria Ugaz and John Washington 2015

Originally published as La fabrica del crimen

Temas de Hoy 2012

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-104-0 (HB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-428-7 (EXPORT)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-106-4 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-107-1 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

For my mom

CONTENTS

1

A CRIME

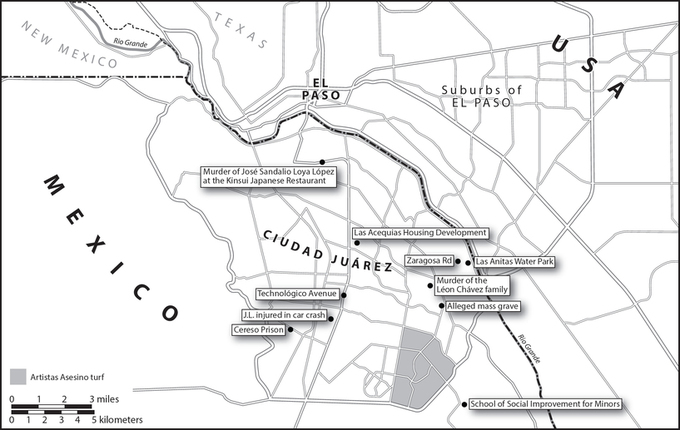

May 2004: a horn blasts into the night, a car alarm screams. Just south of the US-Mexico border a Ford Explorer without license plates and with its front end wrapped around a tree trunk catches fire. The blaze lights up the darkness of Zaragoza Road, a dirt path cutting through the scattered farm fields of this quadrant of the Ro Bravo Valley, the most cultivated area of the otherwise arid outskirts of Ciudad Jurez. Nothing is visible in the darkness except, about 300 yards to the northeast of the smashed Explorer, the water slides of Las Anitas Water Park, silhouetted by the lights of the border wall, which shine down on the dry ditch of desert and split the land in two.

The Explorer wasnt the only car on the road when it caught fire. Nearby was a Jeep Cherokee, which, a few minutes after the Explorer burst into flames, at about three in the morning, took off heading south, away from the border. This isolated strip of Zaragoza Road might seem the perfect place to dump anything that is unwanted. It was really only connected to the urban stain of Jurez by the incongruous waterslide park built in the middle of alternating plots of farm field and wasteland. The nights darkness inundating this stretch of land added to the feeling that distinguishing any person, or any act, would be nearly impossible.

But the nearly abandoned road that the driver of the Cherokee figured to be so perfectly solitary that night was actually the property of businessman Ricardo Escobar, brother of Abelardo Escobar, a member of Mexicos National Action Party (PAN), who two years earlier had been named secretary of agrarian reform under President Felipe Caldern. One of Escobars night watchmen was the first person interviewed by the state police about what occurred on the night of May 21, 2004. From a small hut built along the edge of a field, the fifty-year-old night watchman was jolted awake by the shrieking car alarm, followed by the growl of the Cherokee speeding away. The racket tore him out of bed, and he ran to his front door, where, facing the international border, he could see a burst of flame and, close to one of the poplar trees that hugged the border wall, what he thought was a second truck whose color and model were too dark for him to distinguish. He left the hut to see what was going on but then heard a series of explosions. He would later tell the investigators that he wanted to call the police, but he didnt have a phone. Meanwhile, the Cherokee made a slow getaway, bouncing over the potholes and rubble of the dirt road.

The burning car was reported to the fire department an hour and a half later when, from his patrol car on the Zaragoza International Bridge, a police officer saw what looked to be a brushfire along the edge of the river.

Four months previously, a group of state policemen had been identified as the perpetrators of the kidnapping and murder of twelve persons whose bodies were discovered in the very heart of central Jurez, in an outdoor patio of the housing development Las Acequias. The policemen were accused of working for the Carrillo Fuentes Cartel (also known as the Jurez Cartel), which controlled all the drug-trafficking points in the state of Chihuahua at the time, including the five border crossings between Jurez and the United States. But even after the prosecution and disbandment of the criminally involved policemen, murders and gunfights continued to plague the city. That same year, there were a total of twenty-three victims executed cartel-style; in the previous week alone, there had been four. Though the policeman on Zaragoza International Bridge thought it was only a brushfire, the current spate of violence spurred him to take a closer look.

Firemen came. They fought the blaze for over an hour, the sinister yellow flames flickering along with the flashing blue and red emergency lights.

Lets get out of here, one cop said to the first responding officer.

Nope. You guys stay. This truck may just have a gift for us.

It was after five in the morning, the sky already beginning to blush, when the cops could finally see through the smoke to the blackened skeleton of the truck with the soft-top back. A fireman was the first to approach and peer inside. What he found, he would later say in an interview, was more shocking than anything he had seen in a six-year career fighting fires: the burnt remains of three bodies, almost completely ravaged by the flames, lying on the collapsed backseat. Each of the bodys skulls had exploded in the heat of the fire. One of the bodies didnt have arms or legs anymore. He could see a spine through an open chest cavity. One of the bodies, he noticed, was significantly smaller than the other two.

This was the gift the officers had waited for.

Some six hours earlier, on the evening of Thursday, May 20, three teenagers drove around in an old cherry-red Dodge Intrepid a few miles south of Zaragoza Road on the unpaved Rosita Road, cutting across vacant lots and a smattering of residential areas, farms and garbage dumps. This was the boundary line between the shores of the Rio Grande and the fanning edge of the Chihuahua Desert.

Bouncing over potholes in the Intrepid was a scrawny, brown-skinned teenager and his two best friends. The scrawny kid in the passenger seat was sixteen-year-old Vicente Len Chvez, student of the Colegio de Bachilleres 6, the only high school in the Jurez Valley. Driving the car was Eduardo, a seventeen-year-old El Paso native, who had become Vicentes inseparable friend after the two met at the beginning of the fourth quarter of school that same year. Uziel Guerrero, who Vicente had known for years, dozed in the backseat; he was eighteen years old.

Hidden under his white collared school uniform shirt, Vicente had a .38 caliber pistol tucked between his belt and his gray slacks. On their way to his house, Vicente spoke to Eduardo in a clipped, demanding tone.