Parts of this book, written specially for the Penguin India series on short biographies of Hindu gods and goddesses, are derived from my earlier book, Krishna: The Playful Divine. The writing of both these books has been for me an intensely rewarding experience. It provided me with an opportunity to rediscover Hindu religion and mythology, its loftiness, its pragmatism, its sublime sensitivities and its daring resolve to imbue reverence with humour, passion and tenderness.

In any society, individual autonomy acquires meaning only if it is based on at least a basic knowledge of the conditioning and contextual factors that constitute the inheritance of that society. The malaise of our times is that, in many respects, we, as a nation, are adrift from our own moorings. Forms, symbols and rituals remain, without an understanding of the substance, meanings and precepts that animate them. All the more reason for us to once again familiarize ourselves with the bequest of Krishna.

My thanks are due to David Davidar and Ravi Singh. I hope this edition will help more people understand Indias most popular deity.

Introduction

Krishna is perhaps the most popular Hindu divinity. From time immemorial he has captured the imagination of the Hindu mind, and, in his own inimitable way, provided succour to millions of believers. The purpose of this book is to try and explore the persistence of his appeal. Beyond a point, faith, reinforced over centuries, is not a matter of analysis. But it is often possible to desegregate and examine the components that account for the strength of its hold and the richness of its contents. Krishna is an extremely lovable god. He is a personal saviour. His divinity is accessible and his personality has human resonances in such plenitude that, almost immediately, the gap between the mortal and the immortal is bridged. Unlike other incarnations of Vishnu, Krishna is regarded as a purna avatar, the complete incarnation, encapsulating in himself the entire canvas of emotions and attributes that constitute the ideal human personality.

A study of Krishna is important also for the insight it provides into the concept of divinity in the Hindu ethos. To a foreigner, or a non-Hindu, the escapades of the child Kanha, or the dalliances of Murari, could appear a trifle bizarre. But the attraction of Krishna lies precisely in this exuberance of his multifaceted personality. The gopis adore him as Bal Gopal, the irrepressibly mischievous yet innocent child; they love him as Shyam, the dark and bewitching flute player; the Pandavas and Kauravas vie to have him on their side in the Mahabharata; the percipience of his upadesha gives salvation to Arjuna; and the lure of his personal charm enables millions to alleviate the engulfing ennui of their lives. The godhood of Krishna was never supposed to be put on a remote and aloof pedestal. The love and reverence he invoked was never meant to be monochromatic. I have often felt that a Hindu lives in a kind of harmonious schizophrenia, wherein the vision of the Almighty, serene and beyond all categories at one level, hardly diminishes this joyous and even extravagant humanization, at another. To the Hindu mind, divinity is not necessarily a hostage to conventional yardsticks of behaviour. It is meaningful for the images it evokes, for the emotions it releases, for the ends it achieves and for the sheer joy and bliss it symbolizes and guarantees.

Child

On the eighth day of the waning half of the lunar month of Bhadrapada (August-September), the horizons were suffused with a new joy. The fires in the hearths of holy men burnt without smoke. A gentle wind blew, the sky was clear, and the stars shone with unusual brilliance. Rivers, their waters sweet and clear, flowed with serenity, the lakes were full of lotuses, the trees were in splendid blossom, and the waves of the sea made music. As the midnight hour approached, it appeared as if all of creation was drenched in the moonlight. And then, as the glorious moment arrived, the earth and the oceans trembled. The gods showered flower petals upon the earth. The notes of the divine dundubhi rent the air. Heavenly spirits and nymphsgandharvas and apsarasdanced and sang in abandon. There was a burst of light as fires, long dead, rose high in obeisance. A deep thunder, awesome like the roar of the ocean, rumbled across the clear sky. There fell a hush, and Krishna, the protector of the world, the incarnation of Vishnu, eighth child of Devaki, son of Vasudeva, and nephew of the wicked king Kamsa, was born.

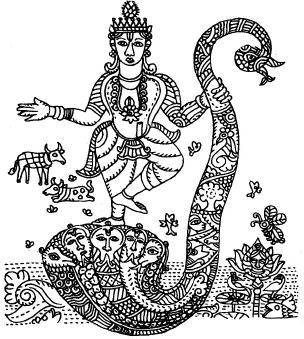

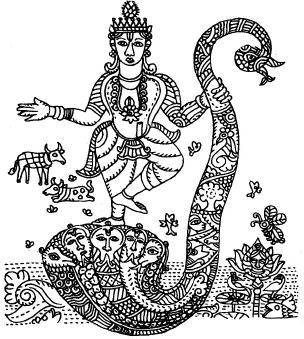

His birth was not an accident. Prithvi, Mother Earth, had suffered long from the depredations of evil and wicked men and women, who had forgotten dharma, the law of righteousness. Crime and persecution had become rampant and, in dread, religion and justice had fled. Kamsa, who ruled Mathura, having usurped the throne from his good father, Ugrasena, was foremost among the wicked. His cruelty was matched only by his arrogance and lack of repentance. Unable to bear this state of affairs any more, Prithvi, assuming the form of a cow, went to Mount Meru, where the godsIndra, Shiva and Brahmahad assembled. Hearing her tale of woe, Brahma approached Vishnu as he lay on his serpent couch in the Milky Sea, and begged the limitless author of creation, preservation and destruction to come to the assistance of Prithvi. Vishnu, ever compassionate, agreed. Plucking out two of his hairs, one black and one white, he said: This, my black hair, shall be incarnate in the eighth child of the wife of Vasudeva, Devaki, and shall kill Kamsa, who is one other than the great demon Kalenemi. The white hair, the Lord said, would also be born to Devaki, as her seventh child. Together the two would kill the demons and rid the world of its accumulated evil.