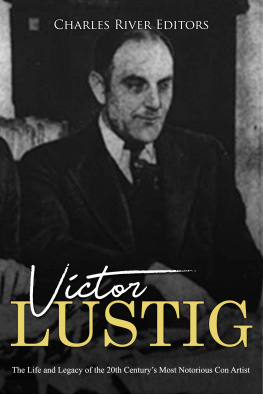

HANDSOME DEVIL

by Jeff Maysh

Table of Contents

1. JAIL BREAKER

VICTOR LUSTIG SAT BROODING on his lumpy prison mattress. It was the Sunday before Labor Day, September 1, 1935, just two days before his trial. The morning had broken bright and clear, and from his grim, third-floor cell in New Yorks Federal House of Detention, the prisoner could see Hobokens serrated skyline across the Hudson River. The towering red-brick jail on the corner of Manhattans Eleventh and West Streets caged the citys most dangerous criminals. It was known to be inescapable.

At 12:30 p.m., the guard unlocked the cell doors one by one, as he did every day. An unruly mob of murderers, stick-up men, and gangsters piled into the narrow corridor, falling over themselves to climb the stairs to the rooftop exercise yard. In the jails history, no prisoner had ever broken free, yet Lustig had made the buildings inner workings his private business. He had tested its weaknesses, turning the guards security rituals into secret time trials in his mind.

From cell D10, Lustig emerged slowly, like a businessman fetching his morning paper. Dark stubble shadowed his rugged face, and with heavy-lidded eyes he watched the inmates with quiet disdain. Prison routine was humiliating for a man who had his suits tailored on Londons Bond Street, and who owned three Rolls Royce cars, each in different colorsincluding purple.

Count Victor Lustig, forty-five, was known to detectives in forty cities as the Scarred thanks to a souvenir from a love rival in Paris: a livid, two-and-a-half inch gash along his left cheekbone. It was an unfitting sobriquet for this 5-foot-7, 139-pound smoothie who was fond of collecting butterflies, and whod never held a gun. Described in the Milwaukee Journal as a story book character, the handsome Austrian dressed like a matinee idol, possessed a hypnotic charm, and was fluent in five languages. As one Secret Service agent later wrote, he could be as elusive as a puff of cigarette smoke and as charming as a young girls dream. And yet his devastating one-man crime spree of clever swindles had rocked Depression-era America.

Lustig strolled along the prison corridor with a silent importance until the guard stepped out of sight. Then, cat-like, he doubled back to his cell and snatched his bulging pillow case. He had three minutes. As the last inmate marched up the stairs, Lustig slipped into the janitors washroom and shut the door. On top of a ventilator pipe he found a hidden pair of pliers, which he tied to his wrist with shoelaces. If he dropped them, he was doomed. He carefully snipped a hole in the thick wire cage that protected the window. Then he forced it open. The three-story drop to the concrete sidewalk looked terrifying.

Inside his pillowcase was the product of a summers hard work. At night when the prisoners howled along to the radio, Lustig toiled away under his covers, tearing bedsheets into strips, dipping them in water, weaving them together. The idea had formed as he watched his cellmate, a violent robber named Noble John Moore, using bedsheets for his morning chin-ups. It took eight weeks to knit a rope forty-six feet long, and Lustig stashed it inside his mattress. Now, alone in the washroom, he tied his rope to the radiator and tugged on it. If it snapped hed be dead. If he was caught, eighty-two years hard time.

Like an urban Tarzan, Lustig swung away from the window. When a group of mildly interested street loungers stopped and pointed, the prisoner took a rag from his pocket and pretended to be a window cleaner. His arms tired and he slipped. Friction burned the skin from his palms, but somehow he landed on his feet. He gave his audience a polite bow, and then sprinted away like a deer.

Repeat that, please? said a Secret Service agent, answering a telephone call from Mr. J. Edelson, a panicked prison guard. Edelson had alerted the superintendent, the Bureau of Investigation, and anyone else he could raise on a Sunday, when a headcount revealed the prison was missing one of Americas most infamous crooks.

The agent stood up and yelled:

Lustig has escaped from the Federal House of Detention!

There was a stunned silence.

Its escape-proof, said a disbelieving voice.

A dozen Secret Service men jumped up and dashed to Lustigs cell. There they found a handwritten note on his pillow, an extract from Victor Hugos Les Misrables: He allowed himself to be led in a promise; Jean Valjean had his promise. Even to a convict, especially to a convict. It may give the convict confidence and guide him on the right path. Law was not made by God and Man can be wrong. Lustig, evidently, felt double-crossed.

The message was flashed to the home of Peter A. Rubano, the Italian-American Secret Service ace for whom Lustig had written the note. It was Rubanos personal crusade to see Lustig behind bars, and in a decades-long game of cat and mouse his man had wriggled free from forty-seven apprehensions. And now Lustig was free again, weaving through a sea of straw boater hats, along Perry Street to the corner of Charles Street, where he hailed a white taxi. Thirty-Fourth Street and Second Avenue, he gasped, his foreign accent sounding to the driver like old money.

Lustig jumped out on the East Side, his size-eight prison sneakers squeaking all the way down Forty-Second Street. He tossed the pliers into the East River with a splosh, and watched the shoelaces trail behind them, sinking into the dark depths. He ran past the busy cigar stands, the fruit sellers, and the movie theaters where actor Robert Donat had wowed audiences as the prison-escaping Count of Monte Cristo. Now, a real mustachioed count was on the run in Manhattan, and the citys newspapermen were ecstatic.

COUNT LUSTIG JAIL-BREAKER! howled the paperboys, hawking bulldog editions of the Herald Tribune. Reams of NYPD red alerts spewed from interstate teletype machines. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover would now hunt Victor Lustig with the same dogged desire that he brought to his other public enemies, John Dillinger and Al Capone. The manhunt was on. But the newsboys and government G-men were short on facts.

Their fugitive answered to forty-seven aliases, was a master of disguise, and was fabulously wealthy. They had locked him away for masterminding a counterfeit cash empire so industrial in scope that it threatened to topple the fragile American economy. Lustig was wanted by detectives not just in America, but in France, too, where he had reportedly soldin an audacious confidence gamethe Eiffel Tower, not once but twice. He was an expert faker, a sleight-of-hand magician, an escape artist, a thief, and a lover. But most importantly, he was free. What Lustig would do next was anyones guess.

2. PSYCHOLOGY OF THE SUCKER

FROM A YOUNG AGE, Victor Lustig dreamed of escape. He claimed that he grew up in Hostinn, under the shadow of the giant Krkonoe Mountains that divide the historic European regions of Bohemia and Silesia. The town is arranged around a Baroque clock tower, and was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when Lustig was born, on January 4, 1890. He was the middle of three children. His father Ludwig and mother Emma were poor peasant people, he said, and they struggled to survive in a grim house made from stone.

Years later the local museum would list Victor Lustig as one of the towns infamous natives, alongside Karel Kl, the inventor of a photomechanical print-making technique that would make Victor a millionaire. Just 850 meters east, the smokestacks of the towns paper mill belch white clouds into the sky. Since the sixteenth century, Hostinn has produced the special paper used to make banknotes.

Victor claimed his parents separated when he was eight. They could not afford to care for him, so he went to live with his fathers relatives. Finding that unbearable, he quit school aged twelve and ran away, taking his chances on the streets of troubled, prewar Europe. In a confession he reportedly made to a high official of the US Secret Service, Victor claimed one childhood event had sparked his criminal career. It happened, he said, on a spring evening in 1903. He was thirteen, scavenging for food outside a Budapest hotel by the banks of the Danube River. Illuminated by the moonlight on a secluded balcony, he spied a beautiful young woman in a gold evening gownan image that printed onto his mind in photomechanical detail.

Next page