TRUE CRIME HISTORY

Twilight of Innocence: The Disappearance of Beverly Potts James Jessen Badal

Tracks to Murder Jonathan Goodman

Terrorism for Self-Glorification: The Herostratos Syndrome Albert Borowitz

Ripperology: A Study of the Worlds First Serial Killer and a Literary Phenomenon Robin Odell

The Good-bye Door: The Incredible True Story of Americas First Female Serial Killer to Die in the Chair Diana Britt Franklin

Murder on Several Occasions Jonathan Goodman

The Murder of Mary Bean and Other Stories Elizabeth A. De Wolfe

Lethal Witness: Sir Bernard Spilsbury, Honorary Pathologist Andrew Rose

Murder of a Journalist: The True Story of the Death of Donald Ring Mellett Thomas Crowl

Musical Mysteries: From Mozart to John Lennon Albert Borowitz

The Adventuress: Murder, Blackmail, and Confidence Games in the Gilded Age Virginia A. McConnell

Queen Victorias Stalker: The Strange Case of the Boy Jones Jan Bondeson

Born to Lose: Stanley B. Hoss and the Crime Spree That Gripped a Nation James G. Hollock

Murder and Martial Justice: Spying, Terrorism, and Retribution in Wartime America Meredith Lentz Adams

The Christmas Murders: Classic Stories of True Crime Jonathan Goodman

The Supernatural Murders: Classic Stories of True Crime Jonathan Goodman

Guilty by Popular Demand: A True Story of Small-Town Injustice Bill Osinski

Nameless Indignities: Unraveling the Mystery of One of Illinoiss Most Infamous and Intriguing Crimes Susan Elmore

Hauptmanns Ladder: A Step-by-Step Analysis of the Lindbergh Kidnapping Richard T. Cahill Jr.

The Lincoln Assassination Riddle: Revisiting the Crime of the Nineteenth Century Edited by Frank J. Williams and Michael Burkhimer

Death of an Assassin: The True Story of the German Murderer Who Died Defending Robert E. Lee Ann Marie Ackermann

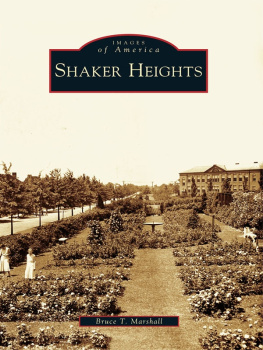

The Insanity Defense and the Mad Murderess of Shaker Heights: Examining the Trial of Mariann Colby William L. Tabac

The Insanity

Defense

and the Mad

Murderess

of Shaker

Heights

Examining the Trial

of Mariann Colby

William L. Tabac

The Kent State University Press Kent, Ohio

The Kent State University Press Kent, Ohio2018 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-60635-352-3

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information for this title is available at the Library of Congress.

22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1

To Joe

Contents

Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer;

nothing is more difficult than to understand him.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, novelist

These psychiatrists, they tell you different things.

George Moscarino, assistant prosecutor, Cuyahoga County, Ohio

In 1965, Mariann Colby, an intelligent, attractive Shaker Heights housewife and mother, shot a nine-year-old neighbor boy to death. Colbys plea to the charge of premeditated murder was insanity. To be acquitted on that ground in Ohio back then, the defense had to prove either that the accused was so ill that she did not know the difference between right and wrong or, if she did, that she lacked the capacity to control herself.

The textbook example of being oblivious to the moral implications of ones actions is an accused who is so delusional that she believes she is slicing a chunk of cheese as she is stabbing someone to death. But Mariann Colby did know the difference: she not only took steps to conceal the crime, but she tried to blame it on someone else. That meant her lawyer had to persuade the judges who heard her case that she was so ill she was unable to control herself.

Under the insanity rules that existed in the sixties, psychiatrists were invited to offer their opinions on that critical issue. Yet, as Mariann Colbys case made its way through the Ohio legal system, the judges and the psychiatrists would sharply disagree over it.

He knew how to use psychiatric testimony, Arthur Rosenbaum, a prominent psychoanalyst, explained about the defense lawyer who had used him as an expert witness in the trial. I had asked Rosenbaum about his role in the case because, a decade later, I was teaching a course in criminal responsibility at the Cleveland State Law School.

Rosenbaums response intrigued me, for no matter how good the psychiatrists were, and no matter how skilled Colbys lawyer was, psychiatrists can only offer an opinion, and when they do, they often disagree. The best person to explain whether Mariann Colby was unable to prevent herself from murdering the neighbor boy might very well have been Mariann Colby herself. But she was not confronted with that question because her lawyer did not put her on the stand, and because of her right not to incriminate herself, the prosecutors were unable to interrogate her.

Was it malice or madness that drove Mariann Colby to murder the child? In taking up that challenging question, this book tells the story of the murder and its aftermath, of its far-reaching effects on the childhood friends of the victim, and of a legal system that was unable to reach a consensus about whether Mariann Colby should be punished or hospitalized for her crime.

William L. Tabac

January 22, 2017

Parkman, Ohio

Along with the individuals mentioned in the bibliography, Dick Feagler was extremely helpful as was Thurston Cosner. My thanks and appreciation also go to the following individuals who provided me with records and documents: The Shaker Heights Historical Society; Becky Hill, head librarian, Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center; Barbara Ellis, Montgomery County, Ohio, Records Center; R. Kramer, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Court of Common Pleas; Jay Ferguson, Ferguson Funeral Home, Hilliard, Ohio; and Halle M. Malcomb, Ohio State Bar Association.

Jess and Lara, my daughters, commented on early drafts of the manuscript and my son, Damon, suggested sources. My wife, Cathy, who faithfully stood by my side through another trying endeavor, wielded a sharp editors pencil.

A special thanks to my friend, Arnold Rheingold, and the late Theron Raines, for their support.

Chapter 1

August 24, 1965

Almost Tenderly

Six miles east of Shaker Heights, Ohio, where the murder took place, lies the village of Gates Mills, a sparsely populated, wealthy community of lavish homes on large, undulating lots. At 11 A.M. on a balmy day, August 24, 1965, the morning of the murder, David Griesinger, a Harvard College student, arrived back at his home in the village from Cambridge. At 11:45 A.M., he rounded up his dogs, two labrador retrievers, for a walk along Gates Mills Boulevard.

Griesinger liked going through forests and woods with his two labs, so he headed off into the woods that bordered the street, never imaginingbecause it was simply impossible for anyone to imagine itthe grisly scene that awaited him there. Two boys, who happened to spot him when he discovered the childs body at 11:50 A.M., reported that Griesinger ran away from the scene. Fifteen minutes later, he called the police from his home.

The Kent State University Press Kent, Ohio

The Kent State University Press Kent, Ohio