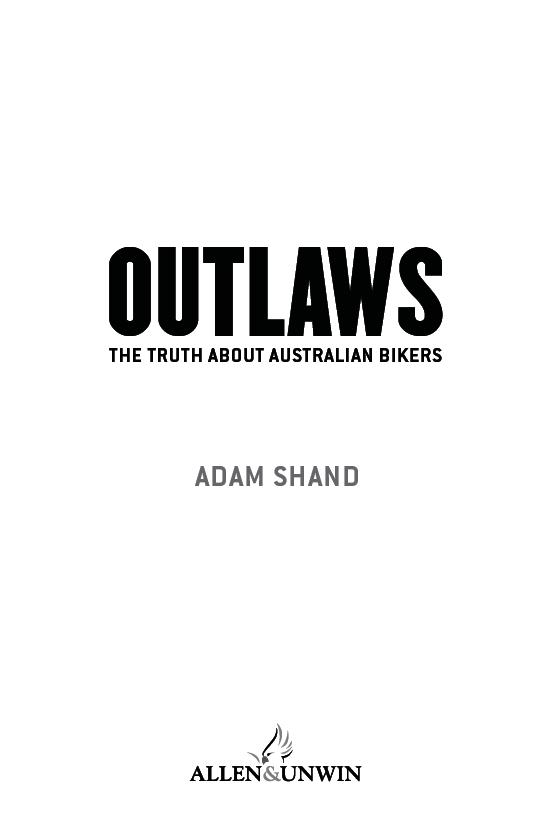

Adam Shand is a leading Australian author and journalist. A Walkley Awardwinning reporter with experience in television, print, radio and on-line, Shand is the author of three other non-fiction titles: BIG SHOTS: Carl Williams & the Gangland Murders , The Skull : Informers, Hitmen and Australias Toughest Cop and King of Thieves: The Adventures of Arthur Delaney and The Kangaroo Gang.

Over a 25-year career, Shand has reported on high finance, African affairs and crime and justice. He is currently a freelance journalist and screenwriter.

Brought to you by KeVkRaY

First published in 2011

Copyright Adam Shand 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74175 979 2

Set in 11.5/16 pt Bembo by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

eBook production by Midland Typesetters, Australia

For my children, Jack and Noliwe.

Popular wisdom isnt always so wise.

Melbourne, March 2011

The driver hears the threat long before the infernal rumble takes ghastly form in his mirrors.

A biker is snaking his way through the cars at the traffic lights. The handlebars of his chopped Harley all but graze the paintwork of the cars as he glides to the front of the queue.

He stops, the bike straddling the pedestrian crossing.

Behind reflective sunglasses, the bikers expression is impassive, but the mouth, amid a thick ginger beard, is set in an expression of grim belligerent assertiveness. He plants his heavy steel-capped boots on the road and crosses his thick tattooed arms across his chest. He is a massive, implacable force.

A man driving a large GM Suburban is displeased at losing his pole position at the lights. He throws a poisonous glare at the bikers back. While everyone else is following the rules, the biker is making his own, doing what he likes.

Its an opportunity to see the beast up close, like viewing a lion at a safari park. Hes dressed in familiar biker garb: faded grimy jeans, a plaid shirt and a leather vest.

Theres no club insignia on the vest, no rocker on the back explaining which gang he is from. Bikers say thats how it is nowif you ride in your club colours youre going to be stopped by cops every five minutes. A day on the bike with a patch on your back becomes a procession of questions, warrant checks and defect notices. So mostly the patch is reserved for massed club runs, quick escapes to the country, or days when you feel defiant enough to take it all on.

But even without the patch, theres no mistaking what he representsthis is the bikie menace. This is the 1 per cent of bikers that no-one else will claim. He lives beyond the pale.

Suburban Man knows all this from shows he has watched on pay TV. Amid the peace and tranquillity of a Sunday morning, its proof the bogeyman still lives. The outlaw has blown in from the wastelands of his worst nightmares.

Suburban Man edges his car forward till the bumper is almost touching the back wheel of the Harley. Hes letting his wife know he wont be intimidated. She wants none of this.

The biker is now aware of the vast chrome grille looming over him. Hes used to this, and to peoples belligerent attitude towards him.

His reputation sparks fear and loathing and he enjoys that. It reminds him that the world is divided into Us and Them. The hatred validates his choice to become an outlaw. Theres no justice; theres just us.

The biker suddenly throws his Harley into gear and, after a cursory check for oncoming traffic, he breaks the red light. But rather than just blast through the intersection, he drops his hip and takes the machine sideways onto the pedestrian crossing. Its the same cheap, irritating manoeuvre that cyclists use every day, but if you pull it on a Harley, it looks infinitely more heinous.

As the back wheel smokes and fishtails, the biker looks at Suburban Man from over his shoulder. Cmon, he seems to be saying, no-one will know and no-one will be hurteven if the cop station is just 50 metres away. Just make a decision.

Then the rider snaps the back wheel under him and opens the throttle. As he guns the bike up the hill, theres a great thunderous roar that echoes off the walls of the concrete canyon.

You can read the disgust on the face of Suburban Man. This is a clear statement, a hideous wet fart in his face: Part of you wants to be me. You would run me off into those parked cars, if you could. But you cant because, in your heart, you are a sheep.

For all his badness, there are moments when the biker feels free, or what he believes it to be. And freedom, even to be bad, is a rare thing indeed.

In 1996 the then South Australian Opposition Leader, Mike Rann, became the herald of a new dark age. He warned of a looming bikie war that state governments up to that point had ignored at their peril.

Rann told parliament that an investigation by New Zealand police into trans-Tasman gang activity had revealed that by the year 2000 there would be just six Australian clubs remaining: the Hells Angels, the Outlaws, the Bandidos, the Rebels, the Black Uhlans and the Nomads. The balance, up to fifty clubs, would be consumed by force or agreement into the Top Six.

It was a powerful and enduring notion, demonstrating that bikers posed a new threat to the social order. A once disorganised rabble, the bikies could apparently form a parallel government, just as US mobster Charles Lucky Luciano had done in creating the National Crime Syndicate for the Mafia back in the 1930s.

The Australia 2000 pact would apparently centralise the control of crime worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year into the hands of the six foundation clubs. Outbreaks of inter-club violence could be tracked back to a fight for supremacy, with the six clubs pushing for exclusive control of turf. Rann said he had been warned of the potential for bikie violence when he visited the FBI that year and at the time had passed those warnings on to the South Australian Police (SAPOL), the National Crime Authority and even in person to the Prime Minister (thenLiberal leader John Howard). But his earnest advice had fallen on deaf ears.

In 2002 Mike Rann became the Premier of South Australia in a minority government. With his background first as a political journalist with the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation and later as a speechwriter for the legendary Don Dunstan, he was media savvy and inevitably came to be dubbed Media Mike. According to Flinders University lecturer Haydon Manning, Rann was a self-consciously constructed leader who assiduously appealed to popular prejudices for his tough and almost perpetual campaign on law and order. Successful leaders command attention and make it look as though they have discovered the neglected concerns of the general public. Rann was a champion of such politics, Manning concluded.

Next page