Contents

Guide

Page List

For Richard & Shirley Thick, with gratitude for all your help

Contents

And this is good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where the Lowells talk to the Cabots,

And the Cabots talk only to God.

JOHN COLLINS BOSSIDY (1910)

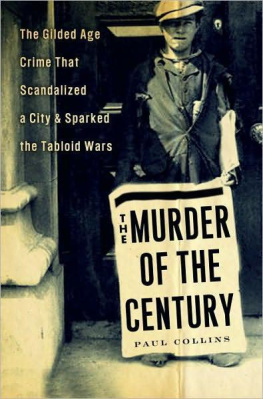

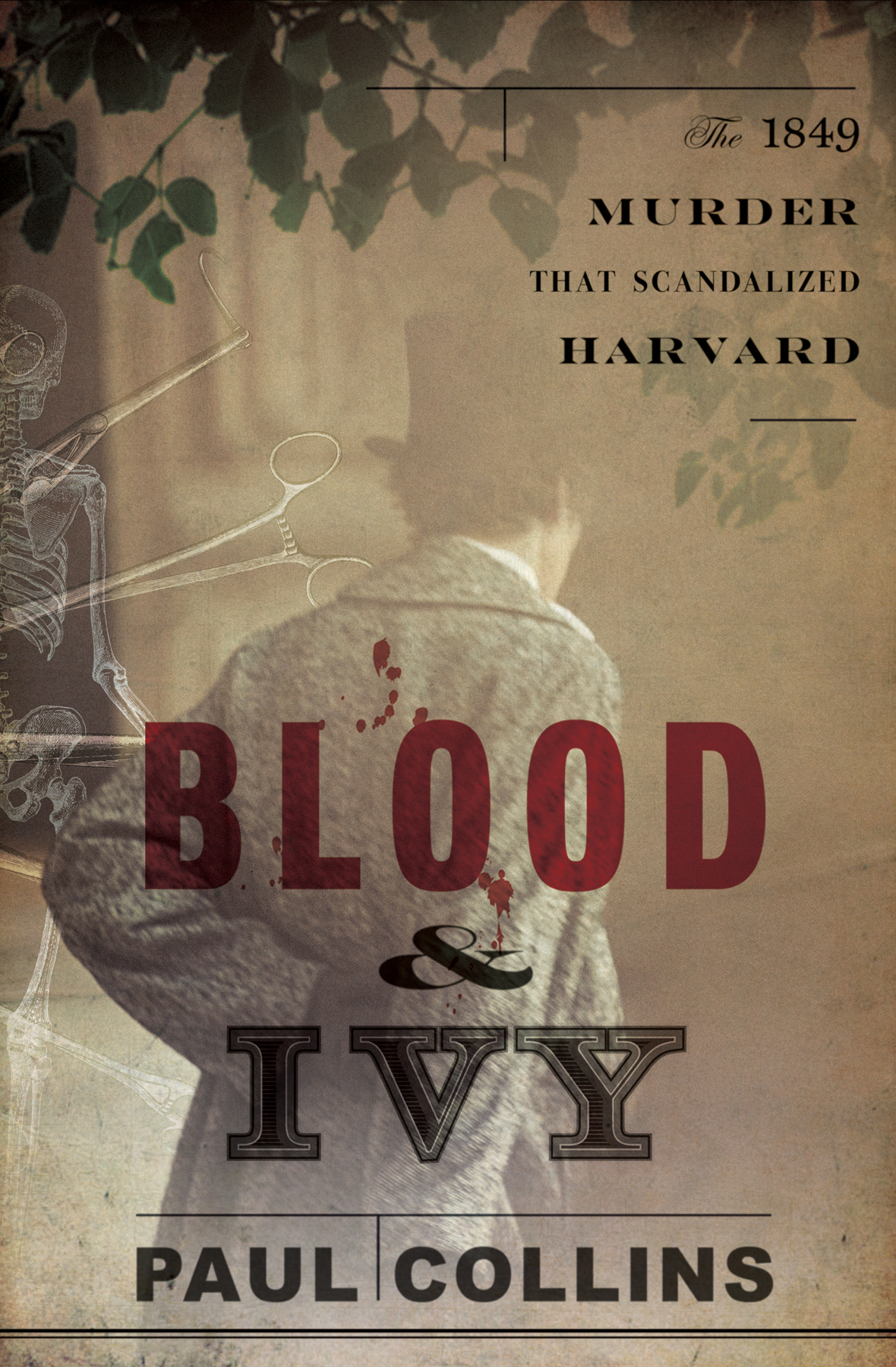

BLOOD & IVY

THE COVERAGE OF THIS CASEINCLUDING A MULTITUDE OF newspaper accounts, letters, journals, court transcripts, and memoirsallowed me to draw on many eyewitness sources. All dialogue in quotation marks comes directly from their accounts; lines rendered without quotation marks are paraphrased. While I have freely edited out verbiage from quotations, not a word has been added.

P.C.

January 5, 1868

IT WAS A MISERABLE NEW YEAR.

The holidays should have been a delight for Charles Dickens; he was on a triumphant stage tour of the United States, his first in twenty-five years. To welcome him back to America, Boston threw off all its customary reserve. The city, the poet Henry Longfellow marveled, was and wrestle with mankind, Dickens reportedhe paced about a suite at the Parker Hotel, musing at the strangeness of it all. Boston was hardly the place hed left behind in 1842.

in five-and-twenty years, he wrote to his daughter. It has grown more mercantileit is like Leeds... but for smoke and fog you substitute an exquisitely bright light air. And it had only one catch: The cost of living is enormous.

This was not for lack of Americans offering to host him. Even after carefully limiting his social engagements to his old literary friends, he spent his days in a whirl of lunches and dinners with the likes of Longfellow, Emerson, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. True, their numbers were diminished by the losses of Thoreau and Hawthorne, and Longfellows leonine mane had given way to a long white beard worthy of Father Christmas. Yet the poet found Dickens much the same as when hed last seen him: twenty-five! He looks somewhat older, but is as elastic and quick in his movements as ever.

Dickenss manner of coping with his fame also remained unchanged: he walked away from it. As was his habit, during his tour he from your front porch without bringing down a two-volumer.

These authors attended Dickenss first show en masse; the group lacked only Melville, who came to a later show. Longfellow, though admitting that .

The tour was generating so much money that Dickens and his road crew almost didnt know where to put it all. , is always going about with an immense bundle that looks like a sofa-cushion.

Yet success couldnt save Dickens from a glum Christmas. He woke up that morning to a fever and a coldan exotic and punishing American variety he couldnt shake. in the world.

It was as well, then, that Dickens took , made one something of a seer: you could stare into an apparently healthy mans future and see that he was about to die.

His old friend Dickens had nothing to worry aboutyet.

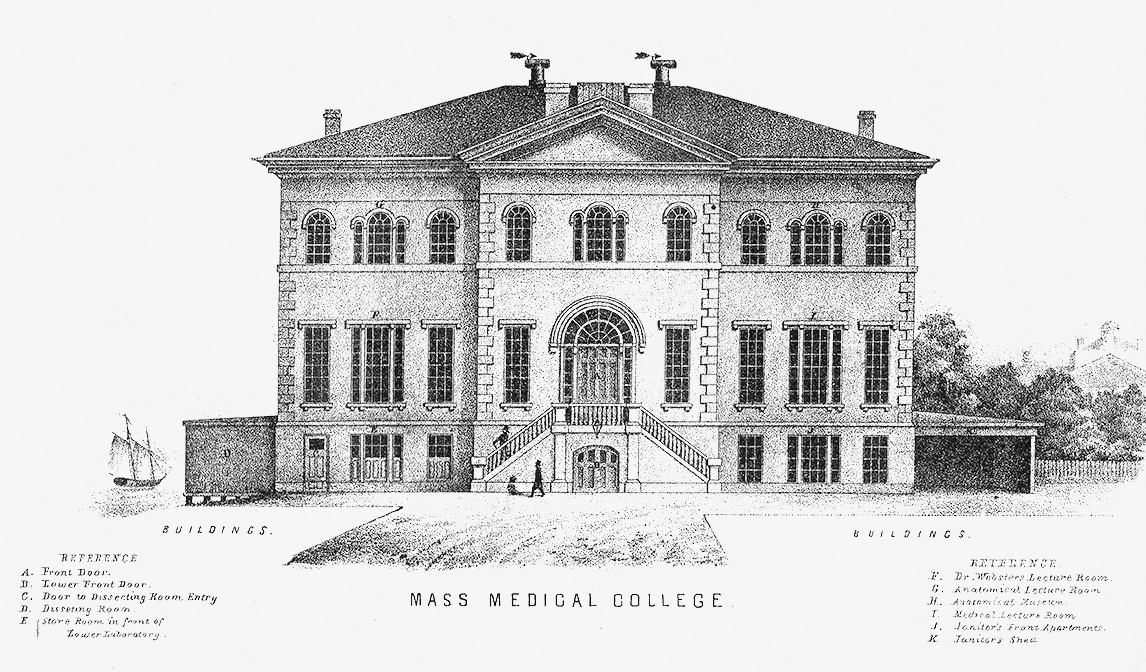

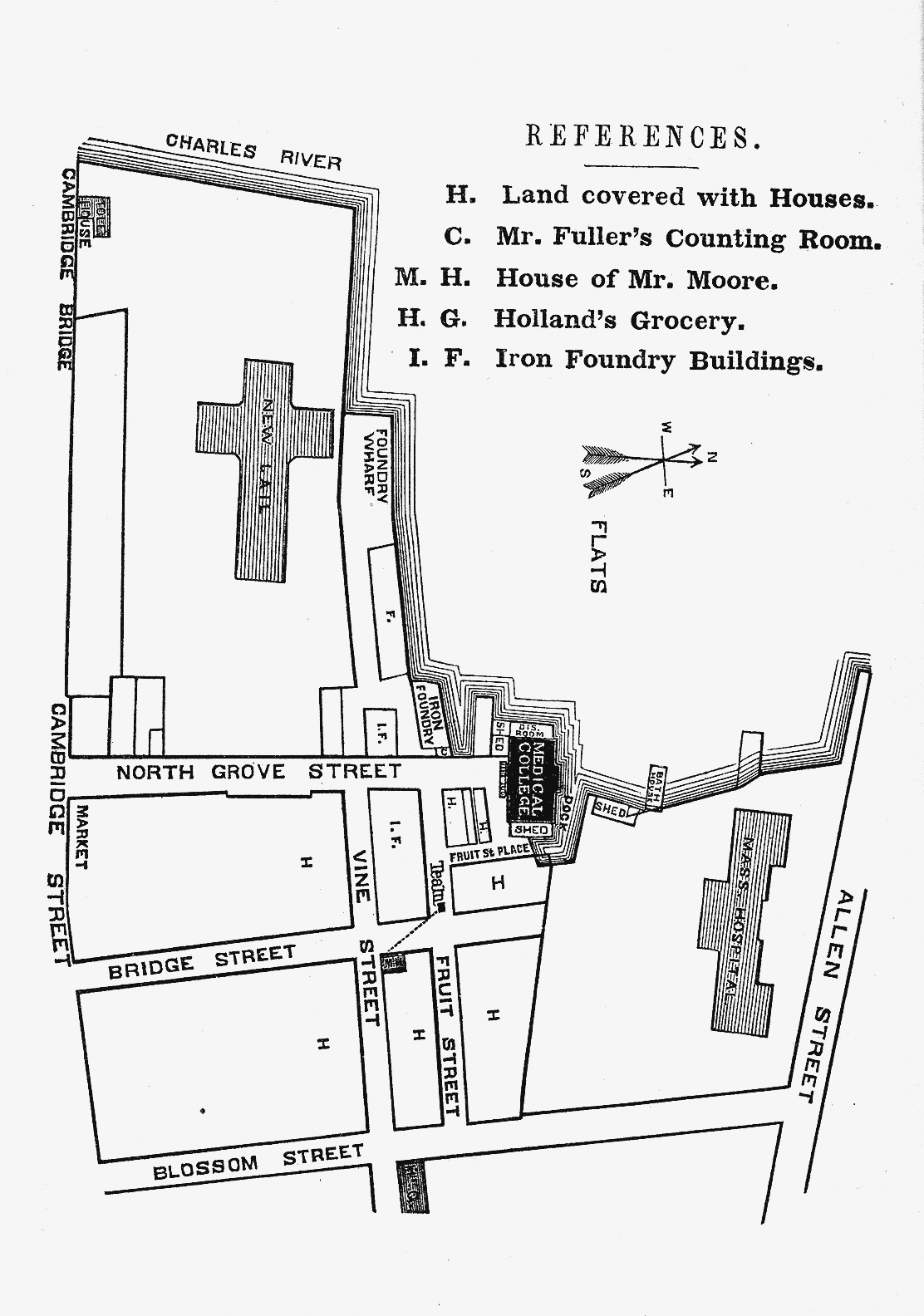

With the ailing author as restless as ever, to the banks of the Charles River, and to the Massachusetts Medical College. Inexorably, their steps went along Grove Street, tracing those of two men whose history weighed upon them. For a tragedy had passed in Dickenss long absence, one shared between the authors and society worthies he had met in Boston: a shocking morality play enacted in their burgeoning city, back when their youth and their country were both beginning to darken.

The murder, Dickens asked. Show me where it happened.

JULY 1849 SAW THE BOYS ARRIVING IN CAMBRIDGE AS THEY had for years: coming over the bridge from Boston, down dusty streets shaded by old elms, and disembarking at a sweltering omnibus station. , there was little else to do but find the local inns or the homes of family friends or relatives, and there, in spare rooms and guest beds, to lie in the oppressive summer night and wait. If they couldnt sleep, there was staring at the ceiling and out the window to occupy them, wondering if they were ready, and if they were even willing, until exhaustion shut their eyes.

When they awoke, it was still dark out.

As the sun rose, they came in from all sides of Cambridge, scores of them, down Harvard Street and Holmes Place, some sauntering across the Cambridge Common, others earnestly keeping to the paths. Harvards campus was empty on this .

All this remained out of reach for now, as the boys seeking admission to Harvard were ushered into University Hall, Room 16. Parents and other family were left outside; the applicants were on their own. In this creaking old room were the others who would become their classmatesand some that wouldnt. The tableau was the same every year.

, in different posturessome full of dread and apprehension, half afraid to meet the eye of others, one applicant wrote of Room 16. Some were full of confidence and boldfull of self respect,observing others,laughing at the awkward or diffident.

Divided into smaller groups by proctors, they were called out, one at a time, into the two adjoining exam rooms. A tutor began with a simple request: State your name, age, month born, and the name of your father.

, said one. I am fifteen years old. Born September. My father is Charles Francis Adams. An unnecessary introduction, perhaps; his namesake grandfather had been president, and his father was on the universitys Board of Overseers.

. Heir to a twine and a cordage manufactoryone of two twine heirs that day, in fact. I am seventeen. Born in May. My father is Moses Henry Day Sr.

, boomed an improbably sonorous voice. The boy had the beard and bearing of a man of forty. I am seventeen years old. Born in February. My father is Philip Dorsheimer. A German immigrants son from New York; new money.

. I am twenty years old, born in December. My father is Artemas White Chamberlain. A Cambridge policemans son. No money.

The rolls continued with each group as they came through the exam rooms. There was , an equally fiery young North Carolinian. Scores more passed through the room, and once the tutor had finished conducting each roll, a printed sheet of sentences in English was placed before every boy.

, they were told.

In the next room, more exercisesthis time translating Latin into English. Then the same exercises, but with Greek. One could also expect to face a professor of Greek for one or two sudden point-blank questions: What cases do verbs of admiring or despising govern? The genitive and the dative, sir. Or, perhaps, a wildly long-haired professor, by turns bemused, distracted, and then remarkably intense, suddenly pouncing: What is (a + b) times (a - b)?