ALSO BY PAUL COLLINS

The Book of William:

How Shakespeares First Folio Conquered the World

The Trouble with Tom:

The Strange Afterlife and Times of Thomas Paine

Not Even Wrong:

A Fathers Journey into the Lost History of Autism

Sixpence House:

Lost in a Town of Books

Banvards Folly:

Thirteen Tales of People Who Didnt Change the World

Copyright 2011 by Paul Collins

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Crown and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

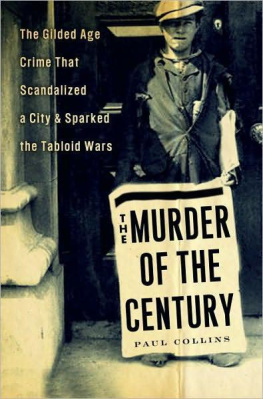

Collins, Paul, 1969

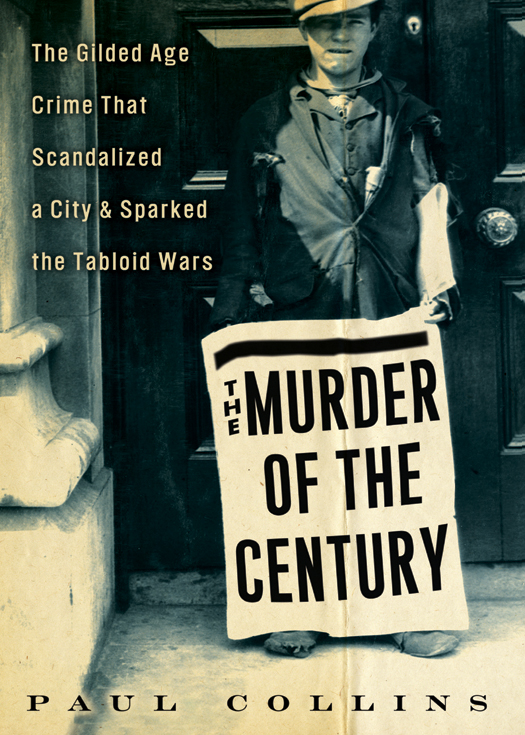

The murder of the century: the gilded age crime that scandalized a city and sparked the tabloid wars / Paul Collins1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Nack, Augusta. 2. MurderNew York (State)New YorkCase studies.

3. Crimes of passionNew York (State)New YorkCase studies. 4. Tabloid newspapersNew York (State)New YorkHistory19th century.

5. New York (N.Y.)History19th century. I. Title.

HV6534.N5C66 2011

364.1523092dc22

2011009390

eISBN: 978-0-307-59222-4

Jacket design by W. G. Cookman

Jacket photograph Bettmann/Corbis

v3.1

To Mom and Dad,

who let me read the mysteries from their bookshelf

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

The tremendous press coverage of this affair, with sometimes more than a dozen newspapers fielding reporters at oncenot to mention the later memoirs of its participantsallowed me to draw on many eyewitness sources. All of the dialogue in quotation marks comes directly from conversations recorded in their accounts, and while I have freely edited out verbiage, not a word has been added.

P. C.

I.

THE VICTIM

1.

THE MYSTERY OF THE RIVER

IT WAS A SLOW AFTERNOON for news. The newsboys along the East River piers still readied themselves on a scorching summer Saturday for the incoming ferry passengers from Brooklyn, armed with innumerable battling editions of Manhattans dailies for June 26, 1897. There were sensational yellow papers like Pulitzers World and Hearsts Journal, the stately flagships of the Herald and the Sun, and stray runts like the Post and the Times. By two thirty, the afternoon editions were coming while the morning papers were getting left in stacks to bake in the sun. But there were no orders by President McKinley, no pitched battles in the Sudan, and no new Sousa marches to report. The only real story that day was the weather: OH! YES, IT IS HOT ENOUGH! gasped one headline. The disembarking ferry passengers who couldnt afford lemonade seltzer from riverside refreshment stalls instead downed the usual fareunsterilized buttermilk for two cents, or sterilized for threeand then headed for East Third Street, where Mayor Strong was giving the dedication speech for the new 700-foot-long promenade pier. It was the citys first, a confection of whitewashed wrought iron, and under its cupola a brass band was readying the rousing oompah Elsie from Chelsea.

Weaving between the newsboys and the ladies opening up parasols, though, were four boys walking the other way. They were escaping their hot and grimy brick tenements on Avenue C, and joining a perspiring crowd of thousands didnt sound much better than what theyd just left. To them, the East Eleventh Street pier had all the others beat; it was a disused tie-up just a few feet above the water, and surrounded by cast-off ballast rocks that made for an easy place to dry clothes. The boys took it over like a pirates landing party, claiming it as their own and then lounging with their flat caps and straw boaters pulled rakishly low. It was a good place to gawk at the nearly completed boat a couple of piers overa mysterious ironclad in the shape of a giant sturgeon, which its inventor promised would skim across the Atlantic at a forty-three-knot clip. When the boys tired of that, they turned their gaze back out to the water.

Jack McGuire spotted it first: a red bundle, rolling in with the tide and toward the ferry slip, then bobbing away again.

Say, Ill get that! yelled McGuires friend Jimmy McKenna.

Aw, will you? Jack taunted him. But Jimmy was already stripped down and diving off the pier. A wiry thirteen-year-old with a powerful stroke in the water, he grabbed the bundle just before the wake from the Greenpoint ferry could send it floating away. Theyd split the loot; it might be a wad of clothes, or some cargo toppled off a freighter. There was no telling what youd find in the East River.

Jimmy dragged the parcel up onto the rocks with effort; the boys found it was the size of a sofa cushion, and heavyat least thirty pounds, tightly wrapped in a gaudy red-and-gold oilcloth.

Its closed, Jimmy said as he dripped on the rocks. The package had been expertly tied with coils of white rope; it wouldnt be easy for his cold and wet fingers to loosen it. But Jack had a knife handy, and he set to cutting in. As kids gathered around to see what treasure had been found, Jack sawed faster until a slip of the knife sank the blade into the bundle. Blood welled out from inside. He figured that meant theyd found something good; all kinds of farm goods were transported from the Brooklyn side of the river. It might be a side of fresh pork.

Im going to see whats in there, he proclaimed, and dug harder into the ropes. As they fell aside, Jack peeled back the clean new oilcloth to reveal another layer: dirty and blackened burlap, tied with twine. Jack cut that away too, and found yet another layer, this one of dry, coarse brown paper. Annoyed, he yanked it off. And then, for an interminable moment, the gathered boys stopped dead still.

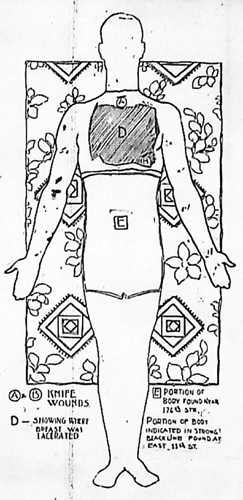

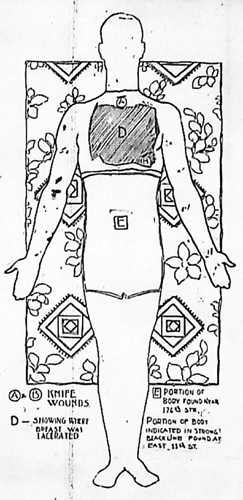

On the rocks before them was a human arm. Two arms, in fact. Two arms attached to a muscular chestand nothing more.

THE POLICE KNEW just who to blame.

Medical students, they muttered as they examined the sawn-off torso. The riverside boys had dithered for half an hour over the grisly and headless find, deciding what to dothough Jack had hastily tossed his knife into the river, afraid of catching any blame. But there was no real cause for alarm; a patrolman arrived and dragged the parcel up onto the dry pier, followed by two detectives from the Union Market station. In no great hurry, they eventually put in a call to the coroners office to note that the med students were up to their usual pranks. The city had five schools that were allowed to use cadavers, and parts of them showed up in the unlikeliest places: Youd find legs in doorways, fingers in cigar boxes, that kind of nonsense. By the time the coroner bothered to pick up the parcel, it had been on the East Eleventh Street pier for three hours, exposed to the curious stares of the entire neighborhood. Meanwhile, boys had eagerly taken to diving into the water trying to find, as one observer put it, every floating object that might by any possibility be part of a human body. They gleefully dragged waterlogged casks, boxes, and smashed timbers onto the pier, but alas, nothing more.