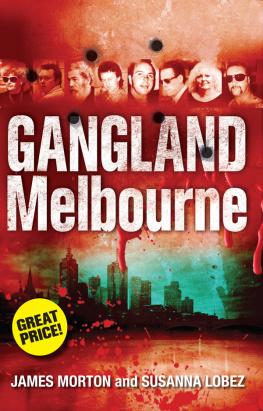

VICTORY BOOKS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2016

Text James Morton and Susanna Lobez, 2016

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited,

2016

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Text design and typesetting by Typeskill

Cover design by Nada Backovic

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Morton, James, 1938 author.

Gangland: robbers/James Morton and Susanna Lobez.

9780522870251 (paperback)

9780522870268 (ebook)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Organized crimeAustraliaHistory.

GangsAustraliaHistory.

True crime storiesAustralia.

Other Creators/Contributors:

Lobez, Susanna, author.

364.1060994

Contents

Introduction

It did not take long after the arrival of the First Fleet in Australia on 24 January 1788 for the robberies to start. On 27 February 1788 Thomas Barrett was hanged for theft and conspiring to steal from government stores. The same year, George Mitton was hanged at Parramatta for robbery. In 1790 William Harris and Edward Wildblood were hanged for a home invasion at Rose Hill, New South Wales, in which they assaulted one of the occupants and stole beef and flour. On 16 October 1794 John Hill was hanged for robbery. Two years later, Governor Captain John Hunter commented on a gang or two of banditti who have armed themselves and infest the country all armed, committing robberies on defenceless people.

It was not until 1828 that the first robbery worthy of the name took place in Australia, with the looting of the Bank of Australia in Sydney. Founded two years earlier, and standing on George Street between a private home and a public house, the bank was regarded as socially superior to the Bank of New South Wales, which had already been in existence for a decade. was not generally popular among the colonists.

The plot to rob the bank seems to have been thought out by a former convict, James Dingle, who had obtained his Certificate of Freedom the previous year. He decided there must be a way of tunnelling into the vault through a drain under George Street, and put the plan to another convict, George Farrell. Other convicts were recruited, and tools supplied by a former London safebreaker, William Blackstone, known as Sudden Solomon, who now worked for a blacksmith. The digging took place at weekends.

Around 11 a.m. on Sunday 15 September, they finally removed the cornerstone nearest the street, and the smallest man, Farrell, went in and brought out two boxes. They went back to the bank on Sunday night and achieved a result that was probably beyond the teams wildest dreams. By the time they emptied the vault, they had taken a total of 14 500. They also destroyed the banks ledgers. An immediate reward of 100 was , the governor, Sir Ralph Darling, offered an absolute pardon and free passage to England to the man or woman who provided information.

The Sydney Monitor thought:

Such however were the unpopular and we will say impolitic principles on which the Bank of Australia was originally founded that among the bulk of Sydneys inhabitants the Banks loss has created secrecy and in many cases open satisfaction

and principal managers are so disagreeable to the Colonists that we feel greatly afraid that facility rather than impediment will be given to the circulation of the stolen notes to such a degree of circulation as will prevent detection.

But, as robbers have found over the centuries, it is the disposal of the proceeds that is sometimes the stage when it is most difficult to avoid detection. Even with the public turning a blind eye, there was no way that passing a 50 note, of which there were 100, would not attract attention; a note greater than 5 would cause serious problems. Nor could bills be paid with handfuls of silver. And so, just as many other robbers have done, Blackstone negotiated with a receiver, Thomas Woodward. His terms were not onerous. Blackstone gave him 1133, and Woodward told him that when he changed it, he would give Blackstone 1000. The pair went to the Bank of New South Wales, where in a classic example of the rort known as the corner game, Woodward instructed Blackstone to wait outside, then simply disappeared through a side door. As many robbers have found to their cost, receivers are not always reliable.

Some months later, Blackstone tried to rob a gambling den in Macquarie Street and was shot by a policeman who witnessed the attempt. Blackstones colleague in the robbery was killed and Blackstone was sentenced to death, which was commuted to life imprisonment. He was sent to the dreaded Norfolk Island, where, unsurprisingly, he disliked the conditions, and in 1831 he decided to shelve, or dob in, his mates from the bank, which might mean his freedom and being able to return to England. Meanwhile, he was lodged on the prison ship Phoenix.

Blackstone did not tell the police the whole story of the Bank of Australia robbery; one of the gang was not arrested, but Dingle and Farrell were charged with breaking and entering, and the now-retrieved Woodward with receiving. They appeared in court in Sydney on 10 June from the English rules of evidence and, by a two-to-one majoritywith the chief justice dissentingdecided that the law was not applicable in New South Wales. Had it been, at that time few people would ever have been convicted. Dingle and Farrell received a very lenient ten years apiece; and the cheating receiver, Woodward, fourteen years.

Blackstone received a pardon, 100 and free passage back to England but had not learned from his experiences. While waiting to be sent back, in July 1832 he was arrested for, but acquitted of, stealing a gun lock in Sydney. In February the next year, shortly before he was due to be shipped back to England, he was caught breaking into a warehouse and was again sentenced to transportation for life to Norfolk Island. in Sydney on 17 March 1850.

but it did survive until 1843, when it folded amid allegations of financial mismanagement.

If the Bank of Australia was not a lucky bank, then a barque called the Nelson was not a lucky ship. Under the command of Captain Walter Wright, and within days of the discovery of gold in Victoria, she sailed from London, arriving in Melbourne on 11 October 1851. With the glitter of gold in their sights, most of the crew promptly jumped ship. The Nelson was then towed to Geelong, and loaded with wool and 8000 ounces of gold, then worth around 30 000. She returned to Melbourne, to find replacement crew. Wright, as befitted a captain, stayed on shore, leaving the ship under the command of the first mate. On board were also the second mate and three other crew members.

On 2 April 1852 a team of men, some dressed as women, others in frock coats, rowed across Hobsons Bay to the

Next page