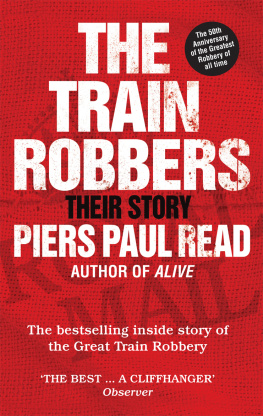

The Great Train Robbery: The Myth of The Ulsterman.

2014 Jim Morris

Jim Morris has asserted his rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

www.eBookPartnership.com

Published by eBookPartnership.com

First published in eBook format in 2014

ISBN: 978-1-78301-549-8

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

eBook Conversion by www.ebookpartnership.com

Contents

The Great Train Robbery: The Myth of The Ulsterman.

Even though there have been ten or so books and countless articles written about the Great Train Robbery, when one considers the sheer volume of documents available for scrutiny in the National Archives and the Postal Archives then it might be true to say that only the bare bones of the story have so far been considered. Details of the planning, the robbery and the aftermath, and a few other facts thought to be of interest, have emerged and been discussed, but there remains much else. Moreover, documents exist that are closed to public viewing: these may not fill in the blanks left by other questions, but they may begin to address them. One question that is absent from many an article and book revolves around the figure known as The Ulsterman, and questions about him have been no more than skin-deep. So its time now to probe a bit deeper.

In the fifty or so years since the robbery we have been fed a diet that consists largely of a few allegedly reliable facts served up from some new angle, but the reliability of the facts was often unchallenged.

When all is said and done though, it was just a robbery, just a crime. But it was one of those events of which there may be only a handful in a decade and something about it captures a piece of history that almost demands its own chapter. Some elements of the story do necessitate the departure from the central core, and subplots of varying degrees of importance hover around the main event. The danger is that they might eclipse it. A similar phenomenon occurred ten years or so later and accompanied the murder of Sandra Rivett, when the disappearance of Lord Lucan took the headlines. Another example is to be found about ten years previous in 1953 when the murder of Sidney Miles was overshadowed by the hanging of Derek Bentley. However, it is possible that the media is manipulated by any number of folk in power, and their focus is on what will sell newspapers now, rather than what will occupy the pages of the history books in the future. The extent to which the media manipulate and even control public perceptions means that discussing the actual becomes a challenge: one needs to set aside what one thinks one knows, and perhaps not correct it, but certainly review the contents before the event can be given a more fitting identity. In the story of the Great Train Robbery the antics of some of the characters involved have tended to overshadow and even blot out some of the main contributors. The robbery itself was just one dimension of the event, so what its worth doing here is having a fresh look at the involvement of both General Post Office (GPO) and British Rail (BR) staff in order to throw a more focused, rather than just a fresh light on the subject.

Most of the people from the GPO or BR can be identified and placed where they should be placed to give structure to any recreation of the nights events, but one of the supporting characters in particular is worth looking at in detail. And thats someone who might have worked for the GPO or BR (or anyone!): The Ulsterman. I can discuss what we think we know about him a little later, but there is one point in the information he was said to have given the robbers that is demonstrably wrong. The Ulsterman is discussed by Piers Paul Read, Bruce Reynolds, and others (myself included), but all commentators have relied on Buster Edwards and/or Gordon Goody for their information as to just what he is supposed to have said. None of us, including Piers and Bruce, could contact Brian Field, the man who had indirectly introduced The Ulsterman and the robbers, because after Brian left prison in 1967 he changed his name and disappeared into obscurity. A fatal car accident revealed his new identity but by then it was too late. An interesting little aside is that in The Definitive Account we are told that Brian served four years in prison and was released in April 1967 so that means he started his sentence in April 1963, about four months before the crime actually occurred, and about a year before the rest of them went into Her Majestys. In any event, one has to ask if Brian would have been able to tell us anything about this mysterious character. There is broad agreement that The Ulsterman briefed the robbers as to the route, timetable and the set-up in the High Value Packages (HVP) carriage, as well as how many men would be working there. But did he actually tell them this? I ask this because if this list is what he did give them, then some of this information was either fairly easy to come by, or was wrong. To start with the route. Trains coming from Glasgow to London travelled the West Coast mainline, GlasgowCarlisleCreweEuston. A trainspotter could tell you this, as could any one of numerous railway magazines available at the time. The timetable is not difficult to obtain and most railwaymen employed at Glasgow and/or Euston would have known the comings and goings of the Travelling Post Office (TPO): there had been a man asking questions at Euston some while before the attack. The set-up of the HVP carriage was also said to have been given by The Ulsterman both Piers and Bruce mention the sorting of mail in this carriage, but that didnt occur, if what TPO staff said is reliable. Rather, that carriage was for the passage and custody of the HVPs only. The confusion on this point, then, suggests that The Ulsterman wasnt quite as described. Nor did he tell them, according to what weve learnt since, about security arrangements in the HVP carriage although again this information might not have been too difficult to come by, and once the robbers had discovered where the train was parked up during the day there would have been opportunity to consider this for themselves. Indeed, they soon discovered that the train was parked up in Camden Town sidings during the day where they could explore the security arrangements at their leisure. As the plan took a few weeks to put together, it wouldnt have been difficult for one or other member of the firm to observe the train and note the position of the HVP carriage. One incidental point to mention is that there were modern, more secure HVP carriages dedicated to the route but were out of commission at the time of the robbery: it was said there was no evidence to suggest that the carriages had been sabotaged, which means no evidence was found. The question of how many men worked in the HVP carriage again degrades The Ulstermans information. Five as quoted by Bruce et al doesnt accord with what the staff on the TPO said. Im sure there was inside information there must have been, there had to be. But, as for The Ulsterman, doubt can now be cast as to whether he was in the plot in 1963 or joined later when the robbers come to tell their tale: later, that is, in the mid-1970s, when Piers Paul Read picked up his pen.