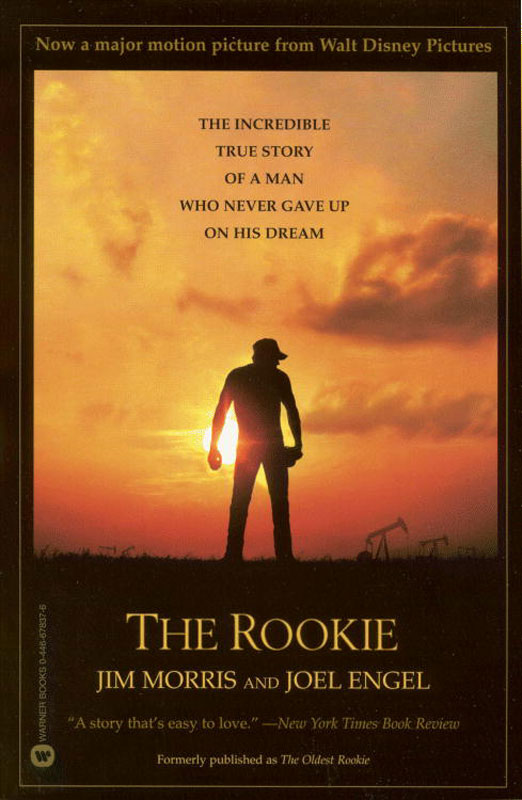

Copyright 2001 by Jim Morris

All rights reserved.

Cover art and billing block Walt Disney Pictures

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

The Warner Books name and logo are registered trademarks of Hachette Book Group

First eBook Edition: March 2002

ISBN: 978-0-446-54987-5

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING ABOUTTHE ROOKIE AND JIM MORRIS'S INCREDIBLE TRUE STORY

The story of his comeback filled me with glee.

Boston Sunday Globe

One of the most improbable baseball careers this side of Kevin Costner.

People

Astonishing . Morris's accomplishments [are] just as amazing as those of the Hall of Famers.

Austin American-Statesman

Too unbelievable to be true.

ESPN

He relates his amazing story with humility and charm.

BookPage

Amazing.

USA Today

You can't make this stuff up . A fabulous baseball story and a fabulous story, period.

Booklist

Inspiring [an] incredible story about second chances.

Library Journal

To my wife, Lorri, who showed me the way when I didn't even know I was lost; and to the 1999 Reagan County High baseball team, who knew me better than I knew myself.

Jim Morris

To my daughter, Maggie, who has big dreams and the heart to make them come true.

Joel Engel

I OWE SPECIAL THANKS to several people: Sarah Burnes, my editor, who somehow turned me into a big-league author; Bill Phillips, who put me on the Little, Brown team; Ron Porterfield, who convinced me that I wasn't too old; Paul Harker, who kept me throwing; Roberto Hernandez, who helped me learn big-league baseball; and Steve Canter, my very own Jerry Maguire.

O NE of my favorite movie actors is Clint Eastwood. The characters he plays are men of few words.

Like me.

All my life I've been quiet. I don't start many conversations, and I answer most questions with a quick Yesor No.You'd know that if you ever had the bad luck to sit next to me at a dinner party. Really, I drive my wife crazy. She's always trying to get me to talk more.

The truth is that I don't think I have much to say, and I don't like to say anything just for the sake of talking. Believe me, it took a long time to accept the fact that people I've never met are interested in my story. Whenever a reporter pointed a notebook or camera in my direction, I checked to make sure that it was really me he wanted.

After nearly a year, I've figured out that it's not me, exactly, who touches people; it's what I represent: the possibility that dreams from long ago may still come true, even if they look lost forever.

That kind of hope is important to the human spirit, more important than I'd realized before I started meeting strangers who wanted only to shake my hand and tell me, Good going.I greeted the smiles of seventy-year-old men as they asked for my autograph, and I read the words of letter writers whom I'd inspired to chase an ancient dream. None of it had to do with baseball. These people were doctors and janitors, executives and retirees. What we shared were dreams from the heart as old as the heart itself. The only difference between us was that my wildest one had suddenly come true.

Why has this happened to me and not to someone else? I don't know. I do know, though, that this dream feels a thousand times more vivid now than it would have fifteen years ago, when I originally intended to live it. In those days, I was too immature to notice how few people are lucky enough to turn their childhood dreams into reality. I had to grow up first and learn to accommodate disappointment, like everyone else. Now, my whole life seems like a dream.

I've written my story as honestly as possible. Whenever I doubted my memory or it failed me, I drew on other people's memories to refresh my recollection. I also consulted documents and published articles and historical archives. The only things I've changed purposely are the names of a few ordinary people, when I thought that not naming them would be more polite.

In that regard, you may wonder why I chose to retell several moments from my childhood in which my parents may appear less than loving. My purpose in reporting these moments was not to shine an unkind spotlight on Mom and Dad; it was to explain the person I've become, because without knowing the full background, you may scratch your head over choices I've made. The truth is that I love my parents and forgive them for whatever they might have done wrong just as they love and forgive me for nearly causing them a dozen heart attacks with my carelessness and daredevilry. They did their best, with each other and with me. I know what happens to you when your dreams break, but even with broken dreams they kept trying to do the right thing, fighting enemies they couldn't see and didn't understand. Some decisions they made were right and some weren't, but everything they did made me what I am. And for that I'm grateful to them.

T HE FIRST THING you need to understand about West Texas is that even local video stores have announcement boards out front with messages like Keep the Christ in Christmas.

The second thing to understand is that, if Jesus Christ himself were to show up on a Friday night in the fall, he'd have to wangle a seat in the high school stadium and wait until the football game ended before declaring his arrival.

In West Texas, high school football and religion are often the strongest links between small towns lying hundreds of miles apart. As you drive down two-lane highways that cut through scrub-brush landscapes littered with deer carcasses and the cars that hit them,your car radio is likely to pull in only two stations, country and religiousand both are likely to broadcast high school football games.

That's how it's been since before my father, Jim Morris, grew up in Brownwood during the era of black-and-white television. A city of about 19,000, Brownwood is in an area of West Central Texas where much of the country's pecan crop comes from. If you're there at the right time of year, when all the pecan trees are blooming, it's something to see. But pecans didn't put Brownwood on the map. Football did.

Even for Texas, the town's devotion to its Brownwood High School Lions is extraordinary. I can't imagine the people of South Bend, for instance, showering Notre Dame heroes with more affection than Brownwood residents and merchants do their home team. They treat football players like celebrities. You're lucky to be a great athlete in Brownwood, and even luckier to be a great athlete from another town whose father is suddenly offered a better job in Brownwood. Everyone wants to play for the Lions.

Yet my dadwho was big, strong, fast, smart, and had an arm like a rocket launcherchose not to play, turning his back on a chance to be Brownwood's maximum BMOC, the starting quarterback. Glory, at least, if not a college scholarship, could have been his. But the new coach hired by the school board before Dad's junior year, 1960, came with a reputation for discipline. And Dad was allergic to discipline. Maybe he was trying to be nothing like his father, who epitomized selfdiscipline. Or maybe Dad modeled himself after James Dean and that whole Hollywood motorcycle-jacket culture. Whatever the reason, Dad preferred to drink, smoke, and chase girlshe was the rebel in search of a party. There'd be time for none of that if he had to practice football five days a week, four hours a day. Many people tried, but no one could sway himnot his father, not the coach. It didn't even matter that pretty cheerleaders favored football players, because his good looks, smooth talking, and come-on smile made him popular enough with other girls.