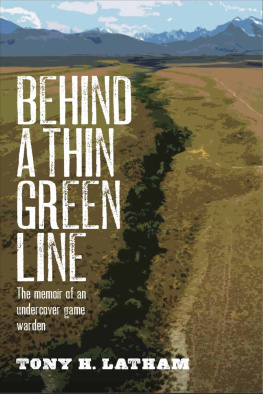

BEHIND A THIN

GREEN LINE

A Memoir of an Undercover Game Warden

By

TONY H. LATHAM

Copyright July 2017 Tony H. Latham

All rights reserved. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material herein is prohibited without the expressed written permission of the author.

Cover Design by Jay Griffith

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Conley Elms and Bill Pogue, two Idaho game wardens gunned downed by a poacher while protecting wildlife.

Foreword

This book is about a collision of poachers and game wardens. The glue that binds this tale is elk. The reader may find it of value to know the history of these marvelous animals, and how close we came to losing them.

In the great scheme of Earth, elk have been in North America for the blink of an afternoon. Fossil records indicate that roughly 15,000 years ago, woolly mammoths and elk expanded their range from northeast Siberia into North America. And sometime after thatafter the eyed needle had been invented and used to stitch together warm clothinghumans began to populate North America from the eastern edge of Siberia.

For thousands of years, people in the Americas didn't have bows and arrows; they hunted with an atlatl. These forearm-long tools were made of wood or bone and greatly increased the speed of a hand-thrown spear. They work much like modern plastic tennis-ball throwers that are made for playing with a dog. The three-foot to four-foot long spears that atlatls throw are called darts. At the aft end of an atlatl, a spur sticks up that fits into a hole in the back of the dart's shaft. This shaft is about four feet long, stabilized with feathers like an arrow and tipped with a double-edged stone point. A good atlatl hunter can put a heavy dart into an animal's chest at 40 paces. Undoubtedly, the first elk felled by man was done with a long dart thrown with an atlatl.

The earliest indisputable evidence of man in Alaska are stone tools and fire hearths that carbon date 8,000-11,000 years B.P (before present). In two of these sites, archeologists found elk bones associated with tools. In Wyoming, elk bones and antler pieces have been recovered from sites dating to about 10,800 years B.P.

Debatably, the first culture that developed in North America is called Clovis and these people were primarilybut not entirelymammoth hunters. The Folsom culture came next and is believed to have developed from the Clovis after the continent's elephants were extinct. Folsom hunters were primarily buffalo hunters and used deeply fluted stone points on their atlatl darts. These points were so difficult to make that it's believed they must have had an unknown significance beyond their lethality. Clovis and Folsom peoples hunted elk, but only on an incidental basis. Subsequent indigenous peoples continued to utilize elk, but very few relied on them as their primary food source.

Ernest Thompson Seton estimated that when Europeans stumbled upon North America, there were about 10 million elk. Evidence shows they were distributed across the continent and were common from the Pacific coast, throughout the Great Plains and the forests of the east coast. With all these elk, why didn't people focus on these big animals as a primary food source?

I've hunted elk for forty-five years using rifles and bows. Except for a few lean years, my freezer had elk in it. If I had been forced to use an atlatl, I'm certain my icebox would have been empty. Here's my theory: people with atlatls could make a living hunting elephants and buffalo since they tend to take a stand-their-ground defense similar to muskoxen forming a circle. But elk don't do that. They blitz. I think that hunter using an atlatl could starve to death before he consistently closed within thirty or forty paces of these long-legged critters.

In the mid-19th century, the situation changed and elk began walking towards a graveyard. The equation that triggered this perfect storm had two veins. The first was what transplanted Europeans called "the Indian problem." In short, Native Americans were obstructing the perceived divine providence we called Manifest Destiny. At the same time, the manufacture of goods had shifted from crafting products by hand in small shops to mass production in factories powered by steam engines and water wheels. The Industrial Revolution was off and rolling. The one material lacking was thick leather for the belting that was needed to distribute power to the machinery.

Buffalo became the solution to both problems and the race to weed the plains began. Twenty thousand men, mostly veterans running from the death and guts of the Civil War, began their bloody work with Sharps rifles and skinning knives.

During this wholesale slaughter, a buffalo skin went for $3.50, while a skin ripped from an elk was worth $7all in a period where the average annual income was $170 a year. If an elk stepped within range of a hide hunter's rifle, a dark cloud of smoke burst from its muzzle, its skin was thrown on the pile and the carcass left for the wolves.

In 1873, Columbus Delano, President Grant's Secretary of Interior wrote,

"The civilization of the Indian is impossible while the buffalo remain upon the plains. I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its effect upon the Indians, regarding it as a means of hastening their sense of dependence upon the products of the soil and their own labors."

Steven Rinella wrote in his iconic book, American Buffalo,

"Along the South Fork of the Platte River, hundreds of hide hunters lined fifty miles of riverbank and used fires to keep the buffalo from getting water at night. In four daytime periods, they gunned down fifty thousand of the thirst-crazed animals."

Luther Standing Bear saw it first hand and wrote about it in his autobiography, My People the Sioux.

"Our scouts, who had gone out to locate the buffalo, came back and reported that the plains were covered with dead bison. We kept moving, fully expecting soon to run across plenty of live buffalo; but were disappointed. I saw the bodies of hundred of dead buffalo lying about, just wasting, and the odor was terrible."

It is estimated that between 30 and 60 million buffalo were killed in twenty-five years. How many other animals were sucked into this holocaust is unknown, but by 1890, Grant and Delano had their wish. Buffalo, elk and grizzlies were gone from the Great Plains and the only thing left were sun-bleached bones and Indians decimated by disease and hunger.

During this same period, gold was discovered in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Thousands of people rushed to the promise of wealth.

This influx needed meat. The demand rapidly outstripped what the ranchers could supply and the only additional source of protein was wild game. Anyone with a rifle and a pack animal could make a quick dollar. Around boomtowns with names like Gibbonsville, Leesburg, and Bayhorse, market hunting became more profitable for some than shoveling pay dirt into a sluice.

Elk were headed into a box canyon and the people of Idaho weren't blind. The situation became so grim that when Idaho's first territorial legislature met in 1863, one of their initial efforts was to pass The Game Act, which established big game seasons and made the sale of game meat illegal when the seasons were closed. The penalty for non-compliance was a civil forfeiture from $5 to $200. What was glaringly absent in this lawin hindsightwas somebody to enforce it.

Wildlife numbers continued to circle the drain. At the end of the 19 th century, elk were nearly extinct in Idaho. In an effort to curtail this, the Idaho legislature passed a law in 1899 shortening the elk season from seven months to one month. It also recognized what market hunting had done and made it illegal to sell game meat. In the same legislation, they created a State Game Warden position with an annual salary of $1200 and directed him to hire a deputy warden for each of the counties,

Next page