Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my parents

Our knowledge isnt much its just a small amount

But you feel it quick inside you when youre down for the count

The Songs We Know Best

Of course Eurydice vanished into the shade;

She would have even if he hadnt turned around.

Syringa

John Ashbery and I met at Bard College in the spring of 2005, when he visited a class I was teaching on modernist poetry and painting. Not long after, he and his partner, David Kermani, invited me to their nearby home. I was expecting a midcentury-modern glass cube and found instead a large, gloomy-looking nineteenth-century Victorian manse. One gray afternoon, I stood on their portico and rang the bell for the first time. Inside, tiny slits of natural light illuminated corners and crevices, but the large center hallway was otherwise very dark. As my eyes adjusted, I could see small and curious objects, many with unusual shapes and textures, covering mantels and tabletops. At some point, as I was feeling both enveloped by darkness and overstimulated by my new surroundings, Ashbery appeared. In his late seventies, he was tall and broad, with very white hair. We toured the house, and he described some things that he particularly liked: a small ceramic plate, a William Morris wallpaper pattern, a Piranesi print. On that visit or another one early on, we sat across from each other on large upholstered chairs in the downstairs sitting room, waiting for David to return with the days newspapers. The room was cool, shadowy, and quiet, and in my sense of surprise at the setting, I felt an inkling of those things or moments of which one / Finds oneself an enthusiast, as Ashbery puts it in A Wave.

Eventually, I spent a summer in the house cataloging objects. Each piece had a story about its provenance. Like the house itself, which Ashbery said closely resembled his grandparents Rochester home, many objects were things he had saved or had replicated from his childhood. Curious about his past, about which very little had been written, I took a trip to Rochester and from there drove thirty miles east to Sodus, to see what remained of his familys farm. Although his mother, Helen, sold the seventy-five-acre orchard in 1965, the handsome Ashbery Farm sign that his father, Chet, made in the 1940s was still hanging out in front of the mostly unchanged farmhouse. Afterward, I visited nearby Pultneyville, the tiny, stunningly picturesque village on Lake Ontario. Young John Ashbery had spent his summers with his grandparents in a small house overlooking the lake. When I returned to Hudson, Ashbery asked me what I had thought. Sublimely beautiful, I said. Isnt it? he replied. Soon after, he, David Kermani, and I drove upstate together, to walk around inside his grandparents Rochester house for the first time since they sold it in 1942. Afterward, we drove through Sodus and Pultneyville, stopping to see inside the farmhouse and to visit other familiar streets and buildings.

One late summers afternoon, I asked Ashbery if he had ever kept a diary in those early years. I was not expecting that he would hand me four small leather books containing about one thousand pages of writing, which he maintained assiduously from the ages of thirteen to sixteen. Started six months after his younger brother suddenly became ill and died, the diaries depict his life and family during a period of mourning. In the 1980s, Ashbery gave the four books to his analyst to read, shortly before the doctor unexpectedly passed away. Fifteen years later, a stranger spotted them among papers he had purchased at an estate sale and returned them. Since then, they had been sitting inside Ashberys dresser, among socks and sweaters. I could peruse them if I wanted, he said, suggesting I just take them home for the weekend so I could see for myself that they were silly and dull and contained nothing of interest.

The diaries were a revelation because the voice of the poet was so present already. In prose entries composed years before it occurred to him to start writing in verse, his wry sense of humor, patience, impatience, and attention to the experience of his experience are unmistakable. Without at first intentionally doing so, the diary also tells, in fragments, and fits and starts, the story of his gradual discovery of and growing excitement about modern poetry. This narrative is all the more moving because it occurred without fanfare in the course of his going to school, visiting grandparents, doing hated farm chores, getting haircuts, listening to the radio, seeing movies, and looking outside at views of lakes and orchards, shifting scenes in sun, rain, and snow. He vividly characterizes his ordinary days, his family and friends. He repeatedly expresses how strange he feels he seems to everyone, including himself. While he dreams of a future life in a big city, far away from the family farm, he also chastises himself for not fitting in better where he is. His likably earnest but self-deprecatory style chronicles in great detail meals, weather, school, reading, writing, painting, playing on the beach in the summer, and first experiences of falling in and out of love with local girls. He relegates important personal revelations, primarily his growing attraction to boys, however, into first Latin, then French, and later an increasingly cryptic language of indirection and absence. It took me a long time to untangle the way these private musings are equally present and bound up with his growing passion for poetry.

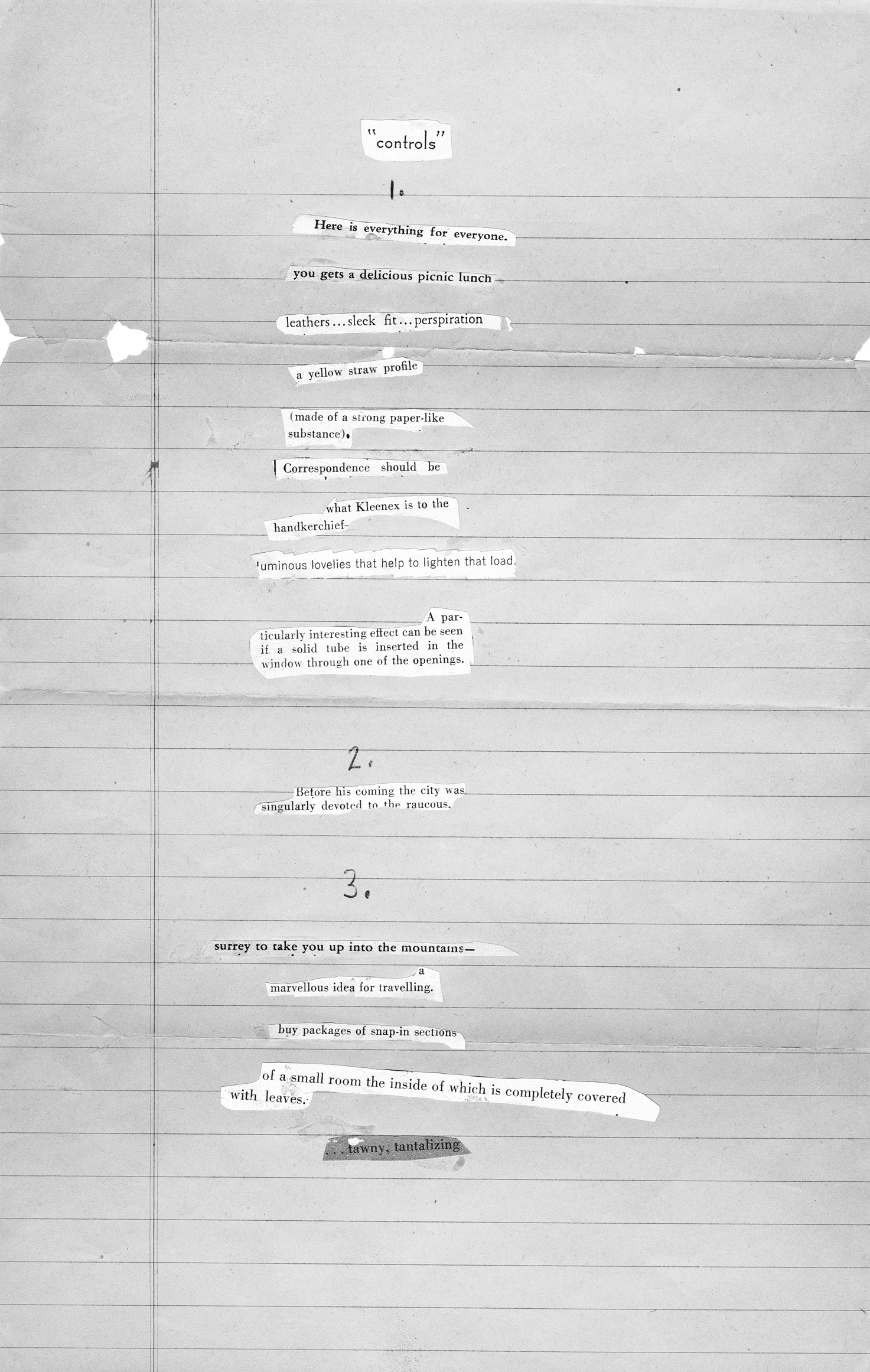

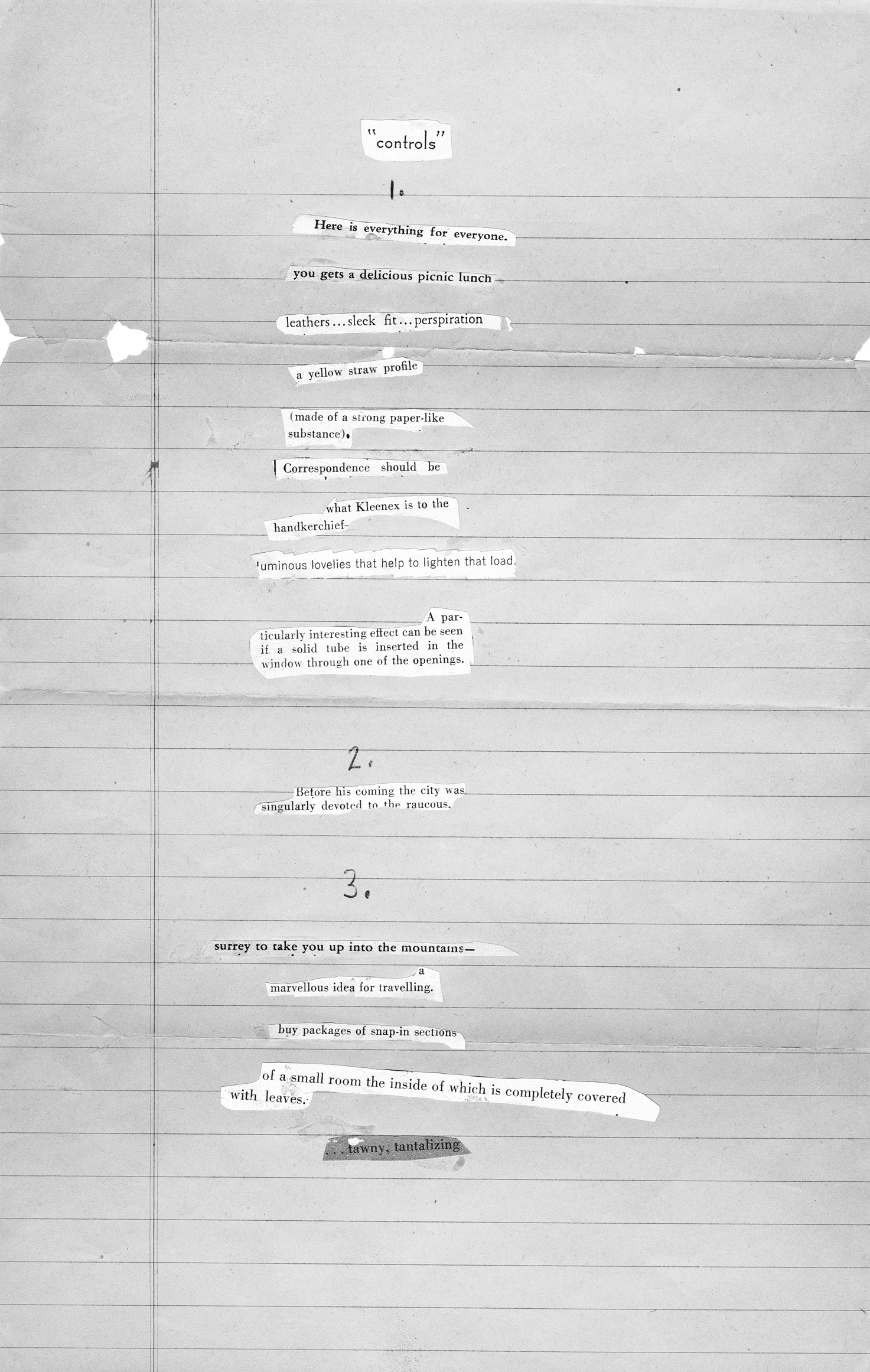

Several weeks after reading the diaries, I found, amid a pile of old newspapers on a shelf in Ashberys downstairs sitting room, a very old typewriter-paper box marked Private. Inside were handwritten and typed drafts of almost all Ashberys adolescent writing: poetry, plays, and stories. Ashbery was shocked to see them, since he believed he had burned them, but they were entirely intact and in fine condition. The diaries talk about what he wrote; the manuscript pages show how. Together, they provide an astonishing record of his earliest creative life.

When I finally formally asked to write a biography of his early life, Ashbery responded that he assumed I already was. He telephoned four close friends and introduced me. Beyond that, he did not interfere. I forged my own relationships with Carol Rupert Doty, the daughter of his mothers closest friend; Mary Wellington Martin, his childhood playmate; Robert (Bob) Hunter, his Harvard roommate; and the painter Jane Freilicher, whom he met the day he moved to New York City in 1949. I visited and talked with each of them multiple times, often staying with Carol on my many research trips to the Rochester area. Their memories of events provided distinct perspectives on stories I already knew and new details to talk about in further interviews with Ashbery. They had all kept photographs and letters, invaluable materials in understanding events and recovering forgotten stories. Although I began with this close group of friends, through meticulous detective work I tracked down more than fifty classmates and acquaintances of Ashberys. Among these were his first boyfriend, Malcolm White, whom he had not seen since 1943. I also found the cameraman Harrison Starr, who filmed Ashbery, James Schuyler, Frank OHara, and Jane Freilicher in James Schuylers play Presenting Jane (1952). It turned out that Harrison Starr still had the film in his garage, a reel that had disappeared sixty years earlier.