This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Souths

400 600 $00

MILES

FOR TAR UN

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012

http://archive.org/details/northofsouthafriOOnaip_0

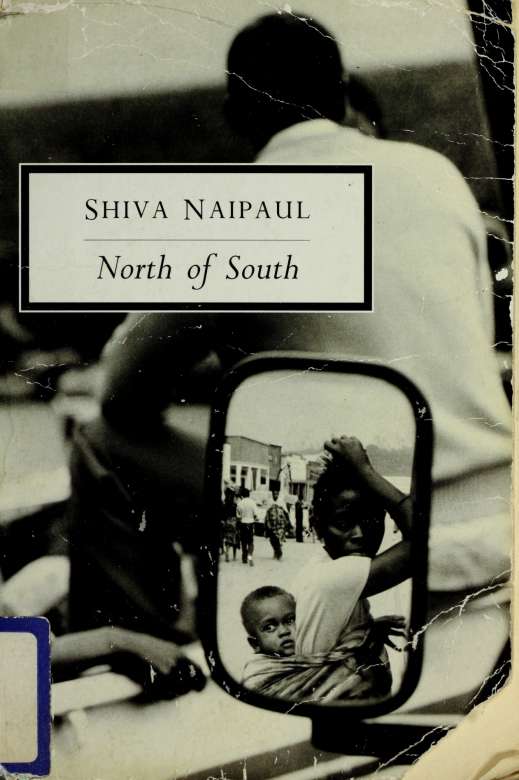

NORTH OF SOUTH

Introduction

An introduction is a temptation: it can turn so easily into a self-justifying exercise, a kind of special pleading in behalf of a book whose nature and purpose might so easily be misunderstood. Especially a book about "Africa"a subject that, in the ex-imperial West, is labeled "fragile," "handle with care," "this side up." In order to avoid temptation, I will repeat here the letter I wrote to my English publisher when the idea of my undertaking an African journey was first discussed.

"Of course [I wrote] it is impossible to be precise about the end product; and, in any case, I don't think it would be wise to overcommit myselfif for no other reason than that the kind of book one eventually writes will be determined by the kind of experiences one has actually had. And I wouldn't care to anticipate what those experiences might be. Still, I shall try to give you some idea of what I have in mind.

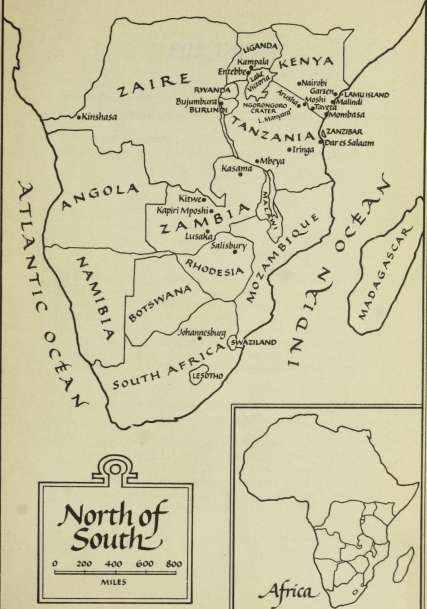

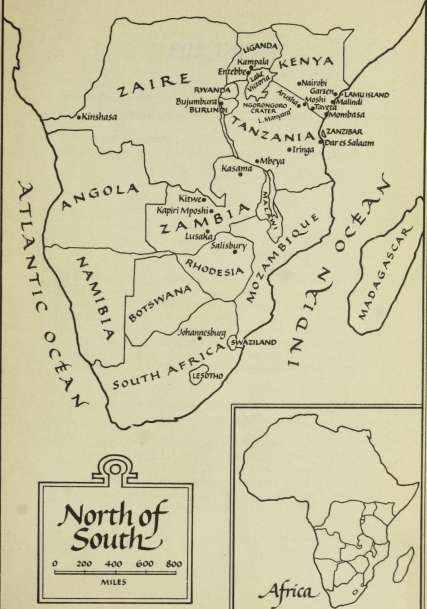

"The idea is that I shall travel in East Africa for a period of (say) five or six months, visiting Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia. But it is not my intention to write a straightforward travel book; nor do I intend to write a 'current affairs' type of book. I won't be setting out to compete with the journalists.

"The book will arise, I hope, out of my own concernsor, if you prefer, obsessions. What do terms like 'liberation,' 'revolution,' 'socialism,' actually mean to the peoplei.e., the masseswho experience them? For example, in Tanzania,

Julius Nyerere has evolved a paternal socialism that he believes reflectsor recreatesall the virtues of traditional African culture. The theory requires that people be moved into villages organized on a cooperative basis. It all looks good on paper, and Nyerere has been much praised. All the same, the attempts to achieve this ideal have involved the burning of crops and homesteads to encourage the reluctant, those who doubt the virtues of ujamaa family hood. Certain questions arise. How wide is the gap between the rhetoric of liberation and its day-to-day manifestations? How much cynicism is there? How much apathy? How much sheer incomprehension? How much fantasy? What kind of Marxism is possible in Africa? The answers to such questions cannot, I believe, be found in the abstract speculations of theorists and professional revolutionarieswho often simply don't see the world in which they live. The answers, I feel, can be found only by experiencing the heat and dust, so to speak, of the countries themselves. Do the people actually care? What are they like as individuals? What is their level of knowledge? Should we despair? Or should we continue to hope?

"Beyond all thisbut not entirely unconnected with itis the relationship of black and white and brown. Very interesting. I would like, for instance, to have a look at the surviving expatriate community in Kenya: the role of white men in independent Black Africa is, to say the least, intriguing. What kind of shadow does the colonial-settler past continue to throw?

"It is possible to go on and on. But I think I have said enough to give you some idea of the kind of book I would like to writenot (to repeat myself) a straightforward travel book or a current affairs book or (God forbid!) a sociological

treatise but (almost) a kind of novel, a montage of people, of places, of encounters seen and interpreted in the light of the questions I have outlined above. I would like to believe that it might be read by people who are not interested in Africa, as such; or in politics, as such."

Since finishing North of South nothing has occurred in Africa that would prompt me to change any of the opinions uttered in it. There has been one event of notethe death of Jomo Kenyatta, the founding father of Kenya. However, the tense of a few passages excepted, his death does not affect anything I have written. Africa goes on.

Shiva Naipaul November 1978

Prelude

Oddly enough, one of the cheapest ways of getting from London to Nairobi is to travel from Brussels via Kinshasa on Air Zaire.

"There's no need to worry," the travel agent had said when I expressed anxiety at the news that he had booked me a flight on the Congolese national airline. "They have good planes Boeingsflown by white pilots."

So Africa began with Air Zaire. To be more precise, it began in one of the transit lounges at Brussels airport.

"You from Kenya?"

A middle-aged Sikh in a blue turban sat down beside me, his gray-bearded face creased into an ingratiating smile. He had, I knew, been eyeing me with intent for some time. Nervous, unable to stay still for more than a few seconds, he took his British passport out of his pocket and looked at it; he leafed through his yellow-paged booklet of vaccination certificates; he examined his air ticket. I did not want to be infected by his alarm.

"No. I'm not from Kenya."

"Tanzania?"

I shook my head.

"Uganda?"

I shook my head.

"Mauritius?"

"I come from Trinidad," I said at last, tiring of the depressing litany of place bred by our Indian diaspora.

"Trinidad ... in the West Indies?"

"Yes."

"Going to Nairobi on business?"

"No."

"On holiday?"

"Yes. On holiday." I watched a plane climbing into the sky.

He was silent for a while. Then: "What is it like for Asians where you come from?"

It was one of the questions to which I was to become accustomed.

"Fine."

"I come from Tanzania. For our people it's no good." He spoke in a whisper and, while he spoke, he looked anxiously about him, as if fearing the presence of eavesdropping enemies.

The public-address system crackled into life.

He grasped my arm. "What is it? What are they saying?" He seemed terrified.

"The flight will be delayed an hour."

He relaxed his grip. He was returning to Tanzania, he said, in the hope of bringing his mother out. But there were problems. There were too many problems. Exit visas, entry visas, foreign-exchange restrictions. It was all too difficult, too complicated. He did not have much hope of success. Still, his mother was his mother. A son always had to try to do his best for his mother. Asians were having a hard time everywhere. Why was that? Why did nobody like Asians? What crimes had they committed? He had heard that even in

Canada they were beginning to have a hard time. Soon there would be nowhere to go. The British were making a fuss about giving his mother an entry permit. What harm could an old woman do? To survive these days you had to be either black or white. It was no good being brown. No good at all.