Peter De Vries - Comfort Me with Apples

Here you can read online Peter De Vries - Comfort Me with Apples full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

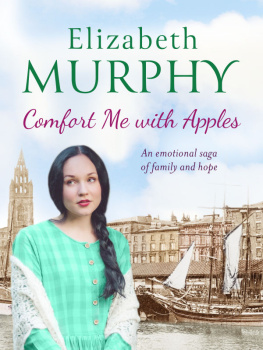

- Book:Comfort Me with Apples

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Comfort Me with Apples: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Comfort Me with Apples" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Comfort Me with Apples — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Comfort Me with Apples" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Comfort Me with Apples

A Novel

Peter De Vries

For Katinka

Stay me with flagons,

comfort me with apples:

for I am sick of love.

THE SONG OF SONGS

One

If an oracle told you you would be a shirtsleeve philosopher by the time you were thirty, that you would be caught in bed with a woman named Mrs. Thicknesse, have your letters used for blackmail and your wife threaten to bring suit for sixty-five dollars because that was all you were worth, you would tell him he was out of his mind. Yet that is what happened to me, and not because I was out of mine. We know the human brain is a device to keep the ears from grating on one another, and mine played that role well in the rational and moral pinches I will try to recreate. What we do in the pinches depends on other equipment and on all that has gone before to make us what we are. The past is prologue. Right, and Man is not a donkey lured along by a carrot dangled in front of his nose, but a jet plane propelled by his exhaust. So perhaps a brief glance at my background is in order.

My sharpest early memory is of a summer-night storm during which we were sought out by lightning. Our family of four (I have a younger sister) were all in the parlor at the time, and saw something nibble the golden fringe of a scatter rug, run over my mothers shoe buckle, lap at wall plugs (not looking for an outlet, just foraging for metal), rummage in an open sewing kit, and browse along a shelf of books, leaving the gilt in some of the titles illegible. I remember thinking that in its career across the living room it seemed to resemble some whimsical and very wicked marmalade. Im not defending this comparison, merely reporting a childhood association itself lightning-swift. Anyway, it bounced off a pair of pinking shears on a table and shot out through the front door into the yard where it ended its call by splitting up a cord of wet kindling.

That was only preliminary to a hurricane, Clara, which howled out of the Atlantic and cut a wide swath which included our city of Decency, Connecticut. Several ships sank, millions of dollars worth of property lay strewn along the Eastern Seaboard, and the salt had to be humored. The wind and rain got almost everything along our municipal beach except a bronze statue of a Minute Man, which had however been battered into neurasthenia by a thousand predecessor storms and now wore a look of Byronic fatigue. Now we know, my father said unclearly. Suggesting that the current may have passed through other matter than I have enumerated.

Those meteorological twenty-four hours have always been to me symbolically like the Mrs. Thicknesse business which struck in later life, and not because her name was Clara, too. Near-calamity is never completely digested; that is, we keep thrilling ourselves with thoughts of what might have happened. The fascination of the narrow escape. Now I can never hear of an amorist being shot in the tabloids, or anywhere for that matter, without evoking, with a delicious shiver, that charged name by which my own and my childrens was so nearly riven. Just as I can never, at breakfast, put a knife to marmalade without spreading coagulated lightning on my toast. All connections are fused.

But to get back to my background.

I think I can say my childhood was as unhappy as the next braggarts. I was read to sleep with the classics and spanked with obscure quarterlies. My father was anxious to have me follow in his footstepsif that is a good metaphor for a man whose own imprints were largely sedentaryand he watched me closely for echoes of himself that were more felicitous than most. He advised people to have intellect, and to look beneath what he called The epithelium of things, though he did discourage scrutiny of his own motives.

Living on a little money my grandmother had left him, he spent his time exercising a talent which was more or less in his own mind. He wrote essays of a philosophical nature which he sent to those periodicals off which he tried to rub some of the bloom on me. They were all returned. This gave him a feeling of rejection (rather than one of submission) and he developed internal troubles. He went to a hospital for observation but they found nothing worse than what they called a sensitive colon, which is I suppose an apt enough ailment for a man as meticulous about punctuation as he was.

The hospital library was nothing to brighten his stay, and he rather truculently offered to send over something decent as soon as he could, a promise he set about fulfilling the minute he got home.

He drove back to the hospital two days after he was discharged, with a few cartons of selections from his own shelves. I rode along and helped carry them in, through the emergency ward, from which the basement room where the ladies auxiliary handled books was most conveniently accessible. It was an icy day in late winter, and I picked my way carefully behind my father with a small boxfulhe toting a rather large packet on his shoulder, like a grocery boy with an order. The walk we traversed sloped upward across a short courtyard, and at a turn in it my fathers foot shot out from under him and, loudly exclaiming Damnation!, he went down, spilling culture in every direction and breaking a leg.

The bone was set free by the hospital, which also gave him a room without cost (No it is not handsome of them to do thisit would be outrageous if they did not!), and soon he was propped up in the same bed again dipping into his old copy of Plutarch, available to him from a trundled cart of books now noticeably enriched as to contents.

What displeased him constitute a history of our time. He could not abide typewritten correspondence or most peoples handwriting. He hated radio and couldnt wait for television to be perfected so he could hate that too. The very word psychosomatic was enough to send him into symptoms for which no organic cause could be found; the decline of human teeth he laid to the door of toothpaste, surely chief among the sweets properly arraigned as villains, as he asserted through dentures which clacked corroboratively. He hated everything brewed in the vats of modernity. He hated music without melody, paintings without pictures, and novels without plots. In other words, a rich, well-rounded life.

The house on the outskirts of Decency we lived in was built around a silo, which became my fathers library. Swiss cheese, except for the silo, comprised the principal masonry, as the dank airs which continually stirred the draperies attested; the wiring was, to put it no lower, shocking; the fireplace drew briskly but in the wrong direction, sending out ashes which settled like a light snow on our family and on the strangers within our gates, for in those years my parents loved to entertain. They had lived originally in a dinette apartment in town but had begun to drift apart and needed more room. The capacious new house did in fact ease their relations, getting them out of one anothers pockets I suppose, and I can still hear my mother wailing over some new kitchen crisis, Oh, God, and my father answering cozily from the silo, Were you calling me, dear?

He believed that the art of conversation was dead. His own small talk, at any rate, was bigger than most peoples large. I believe it was Hegel who defined love as the ideality of the relativity of the reality of an infinitesimal portion of the absolute totality of the Infinite Being he would chat at dinner.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Comfort Me with Apples»

Look at similar books to Comfort Me with Apples. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Comfort Me with Apples and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.