Contents

Page List

Guide

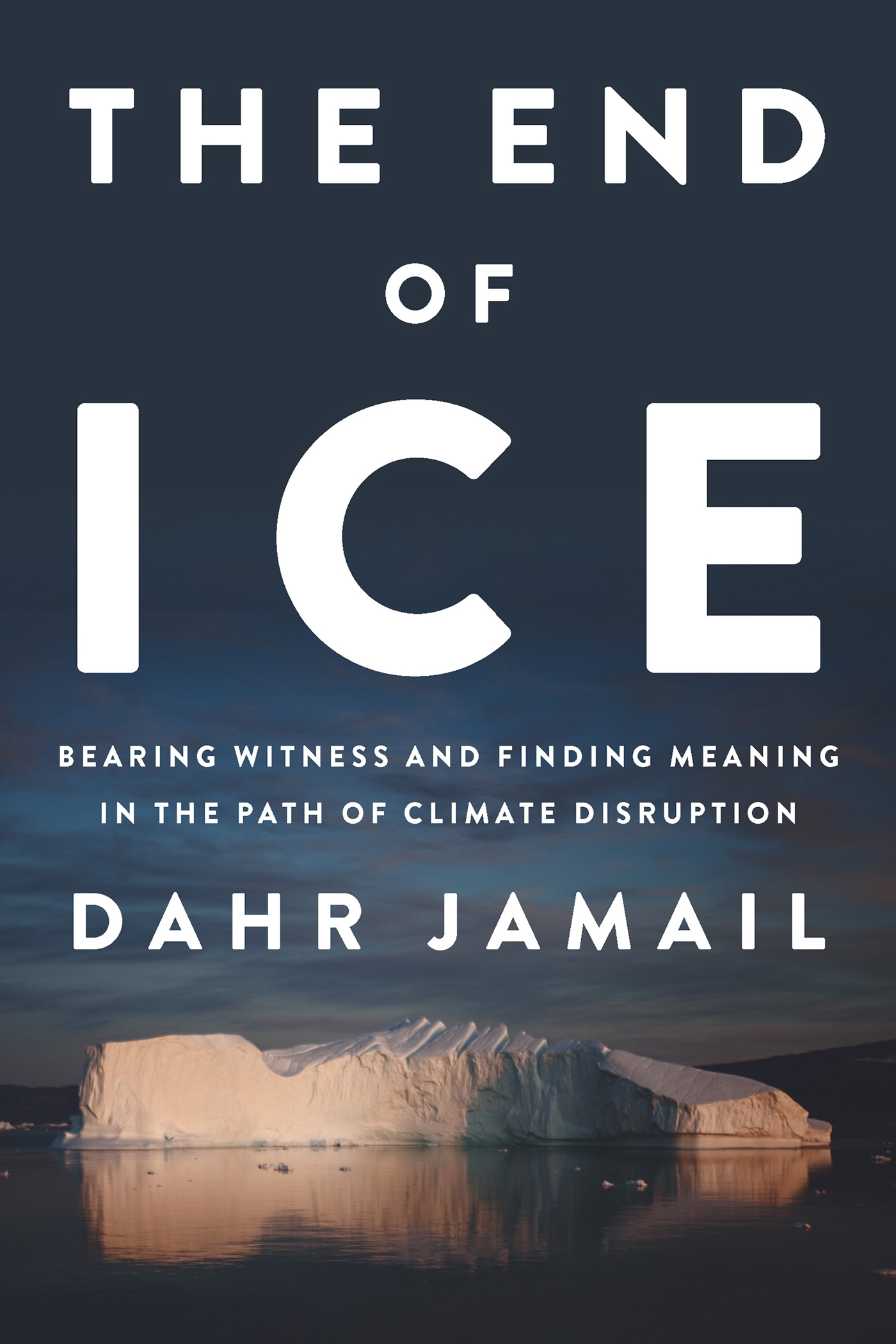

THE END OF ICE

Also by Dahr Jamail

Beyond the Green Zone: Dispatches from an Unembedded Journalist in Occupied Iraq

The Will to Resist: Soldiers Who Refuse to Fight in Iraq and Afghanistan

The Mass Destruction of Iraq: The Disintegration of a Nation (with William Rivers Pitt)

THE END OF ICE

BEARING WITNESS AND FINDING MEANING IN THE PATH OF CLIMATE DISRUPTION

DAHR JAMAIL

2019 by Dahr Jamail

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2019

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-234-2 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-62097-235-9 (ebook)

CIP data is available.

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often handsell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Sabon and Avenir

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the future generations of all species. Know that there were many of us who did what we could.

There are no unsacred places; there are only sacred places and desecrated places.

Wendell Berry

Contents

Introduction

The fall lasts long enough that I have time to watch the blue ice race upward, eons of time compressed into glacial ice, flashing by in fractions of seconds. I assume Ive fallen far enough that Ive pulled my climbing partner, Sean, into the crevasse with me. This is what its like to die in the mountains, a voice in my head tells me.

Just as my mind completes that thought, the rope wrenches my climbing harness up. I bounce languidly up and down as the dynamic physics inherent in the rope play themselves out. Somehow, Sean has checked my fall while still on the surface of the glacier.

I brush the snow and chunks of ice from my hair, arms, and chest and pull down the sleeves of my shirt. Finding my glacier glasses hanging from the pocket of my climbing bib, I tuck them away. I check myself for injuries and, incredibly, find none. Assessing my situation, I find theres no ice shelf nearby to ease the tension from the rope so Sean can begin setting up a pulley system to extract me.

I look down.

Nothing but blackness.

I look at the wall of blue ice directly in front of me, take a deep breath, and peer up at the tiny hole into which Id fallen when Id punched through the snow bridge spanning the crevassethe same bridge Sean had crossed without incident as we made our way up Alaskas Matanuska Glacier toward Mount Marcus Baker in the Chugach Range.

You get to look down one more time, then thats it, I tell myself out loud.

Again, theres only the black void yawning beneath me, swallowing everything, even sound. My stomach clenches. I remind myself to breathe.

Sean, are you okay? I yell as I clamp my mechanical ascenders to the rope in preparation to climb up.

Yeah, Im alright, but Im right on the edge, he calls back. I cant set up an anchor to get out of the system, so dont ascend. Were just gonna have to wait for the other guys to catch up.

Time passes.

The onset of hypothermia means I cant control my body from periodically shaking. To ignore my fear of dying I gaze, meditatively, at the ice a few feet in front of me as I dangle. The miniature air pockets found in the whiter ice near the top of the glacier have long since been compressed, producing the mesmerizing beauty of centuries-old turquoise ice. Slightly deeper into the crevasse is ice that has been there since long before the Neanderthals.

I hang suspended in silence, mindful not to move out of fear of dislodging Sean. Giving my full attention to the ice immediately within my vision, I focus on how the gently refracting light from above seems to penetrate and reflect off the perfectly smooth wall. Staring into it, the blue seems infinite. Despite the danger of my situation, the glaciers beauty calms me.

Delicate snowflakes, in their infinite possibilities of form, land on mountainous terrain. Under its own weight, the snow is compressed into glaciers that scour and shape the face of the Earth. Countless millions of tons of weight, aided by the force of gravity, push and pull these frozen rivers downhill, carving out cirques and troughs from uplifted geologic plates and sculpting the majestic heights of mountains that I have been drawn to since I was young.

Eventually, our two other teammates arrive and work to extract Sean from his perch just six inches from the edge of the crevasse. All three of them set up a three-way pulley system. Laboriously, my teammates begin to haul me up, inches at a time, out of what nearly became my tomb. I continue to focus on the delicately shifting shades of blue in the ice as I draw closer to the surface, mesmerized by its raw beauty.

My teammates pull me up to the lip of the crevasse. I repeatedly plunge the pick of my ice ax into the snow and haul myself out, never before as grateful for being on top of a glacier. I stand and gaze up at a mountain to the west, behind which the sun has just set. Snow plumes stream off one of its ridges, turned into ruddy red ribbons by the setting sun. Snowflakes flicker as they float into space.

As relief floods my shivering body, I roar in gratitude and relief. Utterly overwhelmed by being alive and surrounded by the beauty of the mountain world, I hug each of my three climbing partners. Now safe, it sinks in just how close to death Ive been.

That was Earth Day 2003. In hindsight, I believe the emotion I felt then stemmed in part from something elsea deeper consciousness that the ice that I had seen, which had existed for eons, was vanishing. Seven years of climbing in Alaska had provided me with a front-row seat from where I could witness the dramatic impact of human-caused climate disruption. Each year, we found the toe of the glacier had shriveled further. Each year, for the annual early season ice-climbing festival on this glacier, we found ourselves hiking further up the crusty frozen mud left behind by its rapidly retreating terminus. Each year, the parking lot was moved closer to the glacier only to be left farther away as the ice withdrew. Even sections of Denali, which stands over twenty thousand feet tall and is roughly 250 miles from the Arctic Circle, had undergone startling changes: the ice of its glaciers was disappearing quickly.

Our planet is rapidly changing, and what we are witnessing is unlike anything that has occurred in human, or even geologic, history. The heat-trapping nature of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane, both greenhouse gases, has been scientific fact for decades, and according to NASA, There is no question that increased levels of greenhouse gases must cause the Earth to warm in response. Oceans are warming at unprecedented rates, droughts and wildfires of increasing severity and frequency are altering forests around the globe, and the Earths cryospherethe parts of the Earth so cold that water is frozen into ice or snowis melting at an ever-accelerating rate. The subsea permafrost in the Arctic is thawing, and we could experience a methane burp of previously trapped gas at any moment, causing the equivalent of several times the total amount of CO2 humans have emitted to be released into the atmosphere. The results would be catastrophic.