The crowns of drowned trees form islands along the river margins.

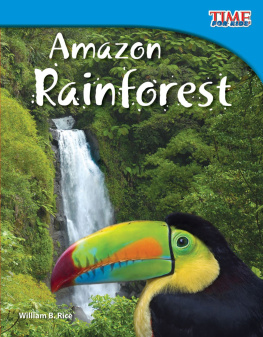

Its the planets richest ecosystem, where a butterflys wing can grow as big as your hand and five hundred species, from frogs to insects, can be found on a single flower. The Amazon basinthe 2,670,000 square miles drained by the Amazon River and its many tributariesis the worlds largest jungle, an area as big as the lower forty-eight U.S. states, the same size of the face of the full moon. Jaguars hunt in the shade of two-hundred-foot-tall trees; pink dolphins, who the local people claim have magic powers, swim in the rivers. New species discovered here in the last decade include a tarantula striped like a tiger, a bald parrot, a vegetarian piranha, and a monkey who purrs like a kitten.

The MV Iracema, one of two riverboats carrying the Project Piaba team on its adventure.

This huge, ancient rainforest is essential to the planet. Because its trees provide a full fifth of the worlds oxygen, its considered the lungs of the world. Yet it all could vanishand soon. Each year, mining, clear-cutting, burning, and cattle ranching destroy an area of Amazon forest twice the size of the city of Los Angeles.

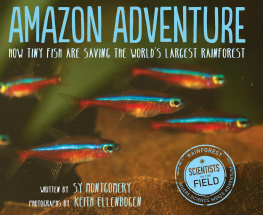

Luckily, beneath the glassy surface of its rivers live dozens of species of tiny, beautiful fish whose powers may be even greater than those of the mysterious pink dolphin or the mighty jaguar. These shy fishso small the locals call them all piaba (pee-AH-bah), which roughly translates to small fry or pip-squeakjust might be able to save the Amazon.

How? Were on our way to find out.

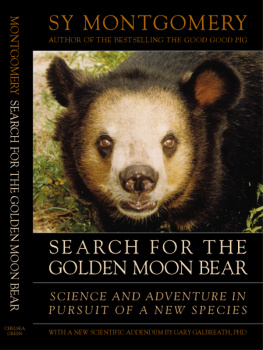

Were traveling by riverboat from the port of Manaus up Brazils Ro Negro, one of the two main arteries that join to form the Amazon River. Our destination, 307 miles to the north, is Barcelos, a town of twenty-five thousand. Each year, fishermen come here from miles around, bringing some forty million of these small, colorful tropical fish that they caught in their forest communities. From Barcelos, the fish will be shipped to Manaus, and from there to public and home aquarium tanks around the world.

A pair of blue and gold macaws.

But wait: Capturing and exporting wild animals from their natural habitat sounds like a terrible ideadoesnt it?

Our host, Scott Dowd, agrees. Thats exactly what I thought when I first came here, he explains from aboard the deck of our boat, the MV Dorinha. A big man with a silvery beard and twinkling blue eyes, Scott knows better now. Today he eagerly admits, I couldnt have been more wrong!

Scott vividly recalls his first trip up the Ro Negro. It was 1991. He was twenty-four years old, and he had teamed up with a prominent professor from the Federal University of Amazonas in Brazil, Dr. Ning Labbish Chao, to charter a boat with ten other fish enthusiasts. Thrilled to be in the green heart of the rainforest, Scott loved watching red and yellow macaws streak across the sky; he loved sleeping in a hammock on the boat at night and waking to the growling roars of howler monkeys in the morning. But mainly he came for the fish.

Today he is senior aquarist with the New England Aquarium in Boston, in charge of twelve thousand fish, frogs, snakes, and turtles in its Freshwater Gallery. Hes always been, as he puts it, a fish nerd. He started keeping fish tanks before he was ten. And, like just about any kid who keeps a freshwater fish tank, many of his first pet fish were species native to the tea-colored waters of the Ro Negro.

Scott Dowd, at home in the dark waters of the Rio Negro.

An adult dwarf pike cichlid.

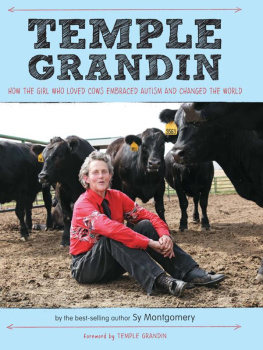

The river water here is stained dark from tanninsnatural chemicals that come from plants whose leaves fall into these pure waters. The tannins make the water acidic. The waters are pristinebut its a hard place to make a living if youre a fish, Scott says. Adaptation to the difficult conditions here has sculpted beautiful and bizarre fish such as cardinal tetras, who glow in the dark with neon stripes of electric red and hyacinth blue; marbled hatchetfish, who can fly out of the water to escape predators; and splash tetras, who spawn on the wet undersides of overhanging tree leaves to keep their eggs safe (the male lurks below in the water for days and uses his fins to throw water up at the eggs to keep them moist). Scott could not wait to visit Barcelos, the town from which so many of the fish he had kept as a child and tended at the New England Aquarium had been shipped.

The rivers glassy surface reflects the trees and the sky.

But when his group finally arrived at the town, Scott was horrified. The riverfront was jammed with men in dugout and plank canoes. They had come from an area of rainforest the size of Pennsylvania, bringing hand-woven plastic-lined baskets full of living fish that would fill hundreds of eight-gallon tubs, each containing eight hundred fish. There were so many tubs that they covered the entire bottom floor of the eighty-foot ferry that was docked at the pier, readying to return to Manaus.

My knee-jerk reaction was, This is out of control! Scott remembers. I thought, we shouldnt be taking wildlife from the rainforest; we should be farming them!

But back then, he says, he didnt realize what would happen if the fishermen simply left these fish alone.

In the Amazon rainforest there are only two seasons: wet and dry. During the wet season, which corresponds to North Americas winter and spring, it rains every day and the forest floods. Trees stand up to their crowns in water. People build houses on stilts, or on pontoons so they can float. Kids dont take a bus to schoolthey take a boat. Then, in the dry season, during our summer and fall, the water level dropssometimes more than thirty feet. Nearly ninety percent of the small fish here are stranded, doomed in drying puddles.