Among the Forest People

by

Clara Dillingham Pierson

Yesterday's Classics

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Cover and Arrangement 2010 Yesterday's Classics, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

This edition, first published in 2010 by Yesterday's Classics, an imprint of Yesterday's Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by E. P. Dutton & Company in 1898. This title is available in a print edition (ISBN 978-1-59915-018-5).

Yesterday's Classics, LLC

PO Box 3418

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

Yesterday's Classics

Yesterday's Classics republishes classic books for children from the golden age of children's literature, the era from 1880 to 1920. Many of our titles are offered in high-quality paperback editions, with text cast in modern easy-to-read type for today's readers. The illustrations from the original volumes are included except in those few cases where the quality of the original images is too low to make their reproduction feasible. Unless specified otherwise, color illustrations in the original volumes are rendered in black and white in our print editions.

To the Children

Dear Little Friends:

Since I told my stories of the meadow people a year ago, so many children have been asking me questions about them that I thought it might be well to send you a letter with these tales of the forest folk.

I have been asked if I am acquainted with the little creatures about whom I tell you, and I want you to know that I am very well acquainted indeed. Perhaps the Ground Hog is my oldest friend among the forest people, just as the Tree Frog is among those of the meadow. Some of the things about which I shall tell you, I have seen for myself, and the other stories have come to me in another way. I was there when the swaggering Crow drove the Hens off the barnyard fence, and I was quite as much worried about the Mourning Doves' nest as were Mrs. Goldfinch and Mrs. Oriole.

I have had a letter from one little boy who wants to know if the meadow people really talk to each other. Of course they do. And so do all the people in these stories. They do not talk in the same way as you and I, but they have their own language, which they understand just as well as we do English. You know not even all children speak alike. If you and I were to meet early some sunshiny day, we would say to each other, "Good morning," but if a little German boy should join us, he would say, "Guten Morgen," and a tiny French maiden would call out, "Bon jour," when she meant the same thing.

These stories had to be written in the English language, so that you could understand. If I were to tell them in the Woodpecker, the Rabbit, or the Rattlesnake language, all of which are understood in the forest, they might be very fine stories, but I am afraid you would not know exactly what they meant!

I hope you will enjoy hearing about my forest friends. They are delightful people to know, and you must get acquainted with them as soon as you can. I should like to have you in little chairs just opposite my own and talk of these things quite as we used to do in my kindergarten. But that cannot be, so I have written you this letter, and think that perhaps some of you will write to me, telling which story you like best, and why you like it.

Your friend,

C LARA D. P IERSON.

S TANTON, M ICHIGAN,

April 15, 1898.

Contents

L IFE in the forest is very different from life in the meadow, and the forest people have many ways of doing which are not known in the world outside. They are a quiet people and do not often talk or sing when there are strangers near. You could never get acquainted with them until you had learned to be quiet also, and to walk through the underbrush without snapping twigs at every step. Then, if you were to live among them and speak their language, you would find that there are many things about which it is not polite to talk. And there is a reason for all this.

In the meadow, although they have their quarrels and their own troubles, they always make it up again and are friendly, but in the forest there are some people who can never get along well together, and who do not go to the same parties or call upon each other. It is not because they are cross, or selfish, or bad. It is just because of the way in which they have to live and hunt, and they cannot help it any more than you could help having eyes of a certain color.

These are things which are all understood in the forest, and the people there are careful what they say and do, so they get on very well indeed, and have many happy times in that quiet, dusky place. When people are born there, they learn these things without thinking about it, but when they come there from some other place it is very hard, for everybody thinks it stupid in strangers to ask about such simple matters.

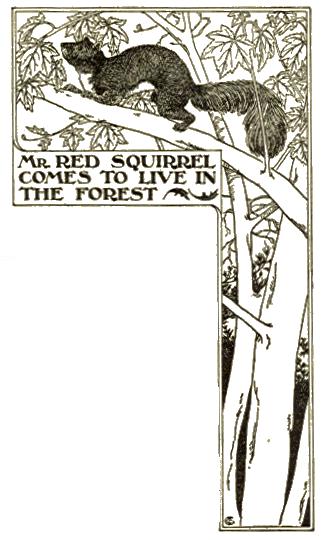

When Mr. Red Squirrel first came to the forest, he knew nothing of the way in which they do, and he afterward said that learning forest manners was even harder than running away from his old home. You see, Mr. Red Squirrel was born in the forest, but was carried away from there when he was only a baby. From that time until he was grown, he had never set claw upon a tree, and all he could see of the world he had seen by peeping through the bars of a cage. His cousins in the forest learned to frisk along the fence-tops and to jump from one swaying branch to another, but when this poor little fellow longed for a scamper he could only run around and around in a wire wheel that hummed as it turned, and this made him very dizzy.

He used to wonder if there were nothing better in life, for he had been taken from his woodland home when he was too young to remember about it. One day he saw another Squirrel outside, a dainty little one who looked as though she had never a sad thought. That made him care more than ever to be free, and when he curled down in his cotton nest that night he dreamed about her, and that they were eating acorns together in a tall oak tree.

The next day Mr. Red Squirrel pretended to be sick. He would not run in the wheel or taste the food in his cage. When his master came to look at him, he moaned pitifully and would not move one leg. His master thought that the leg was broken, and took limp little Mr. Red Squirrel in his hand to the window to see what was the matter. The window was up, and when he saw his chance, Mr. Red Squirrel leaped into the open air and was away to the forest. His poor legs were weak from living in such a small cage, but how he ran! His heart thumped wildly under the soft fur of his chest, and his breath came in quick gasps, and still he ran, leaping, scrambling, and sometimes falling, but always nearer the great green trees of his birthplace.

At last he was safe and sat trembling on the lowest branch of a beech-tree. The forest was a new world to him and he asked many questions of a fat, old Gray Squirrel. The Gray Squirrel was one of those people who know a great deal and think that they know a great, great deal, and want others to think so too. He was so very knowing and important that, although he answered all of Mr. Red Squirrel's questions, he really did not tell him any of the things which he most wanted to know, and this is the way in which they talked:

"What is the name of this place?" asked Mr. Red Squirrel.

"This? Why this is the forest, of course," answered the Gray Squirrel. "We have no other name for it. It is possible that there are other forests in the world, but they cannot be so fine as this, so we call ours 'the forest.' "