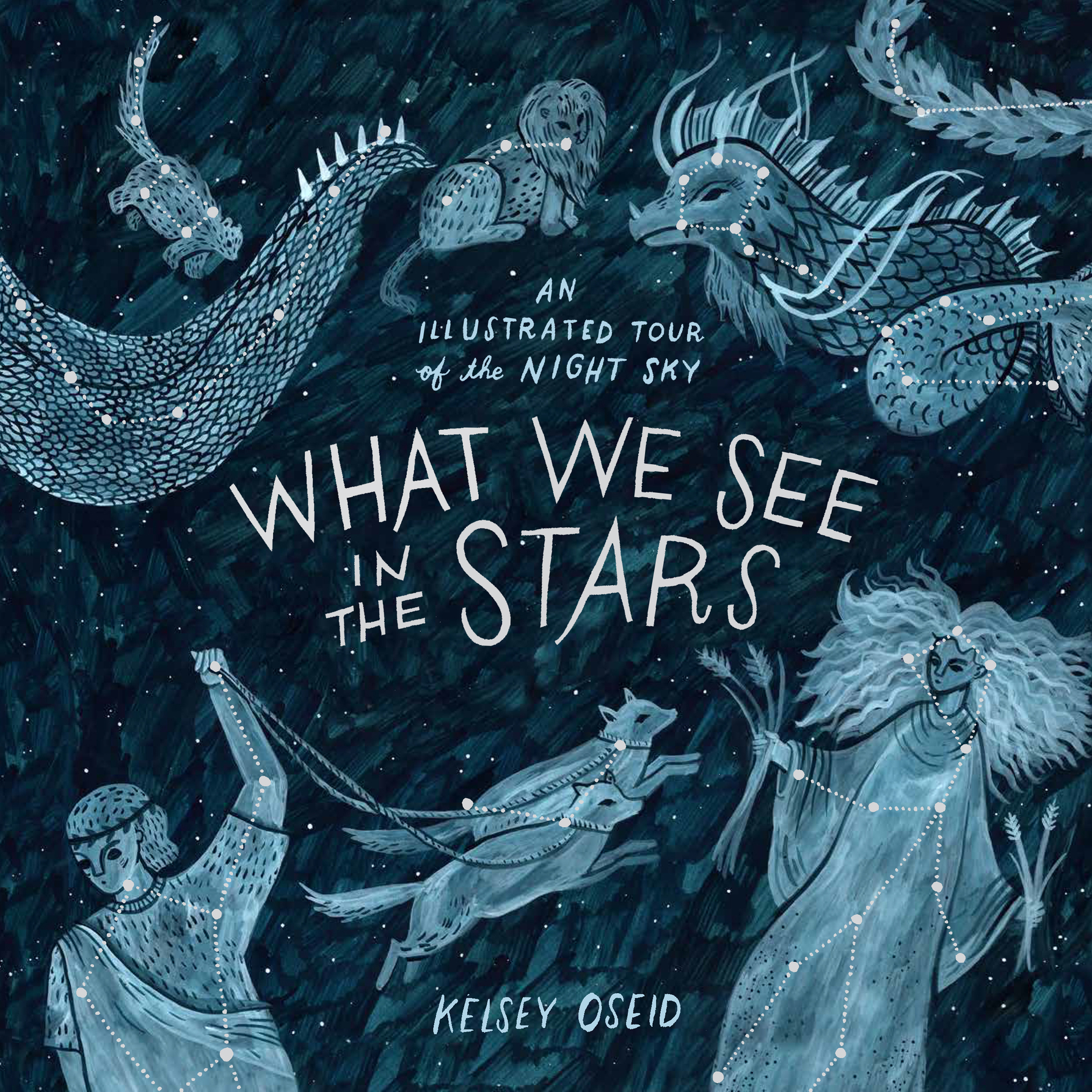

For most of human history, our understanding of the cosmos was based not on scientific evidence, but on our direct observations of the night sky as we gazed up at its sparkling, dark expanse.

We once imagined the sky to be something like a hollow, spherical shell surrounding the Earth, and stars as bright points on that shell. When we began to notice that some of those bright points took different paths across the sky than the rest, we altered our explanation: the Earth was encased not by one sphere, but by many perfectly transparent crystal spheres nested inside one another and spinning in different directions. Onto these, we mapped constellations, the sun, and the moon.

Our old theories about how the universe worked were flawed, but stargazing was still key to some of humanitys most important achievements. Calendars based on the movement of the sun, moon, and stars were important to the development of early agriculture. Navigation based on the positions of the constellations helped explorers sail the globe. The importance of the stars in our history is undeniable.

With so many of us spending a majority of our time indoors and living in light-polluted cities, our stargazing is often limited to occasionally noticing the moon on a particularly luminous night. Even the Milky Wayour own home galaxy that appears as a soft stream of light stretching across the skyis impossible to see when drowned out by the artificial light of our modern world. We can forget the magic of the night sky.

To take a moment and gaze up is to connect to an ancient human experience, and can be a great source of wonder and awe. This book is a tour of the night sky, centered on the old names and stories still in use by astronomers today. It will cover the most brilliant features of our solar system: the constellations, the moon, the bright stars, and the visible planets. And it will delve into less familiar celestial phenomena too, like the outer planets and deep space. Through it all, well explore some of the ancient mythology behind our night sky, as well as the basic science behind what we seeand dont seein the stars.

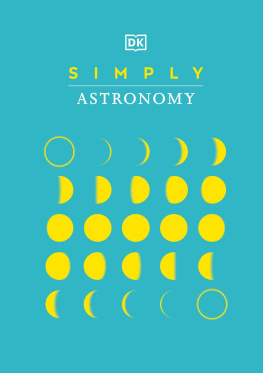

The official border of Ursa Major is defined by the starry blue shape you see here. The shape of the constellation as its traditionally imagined is denoted by the dotted lines, and the solid lines mark its familiar asterism, the Big Dipper .

Constellations are at once something very old and something very young. Weve given them ancient-sounding namesAquila, Hydrus, Equuleus, Grusbased on words from now-dead languages. And weve ascribed ancient myths to them, full of gods, magic, adventure, and vengeance. What could feel older?

But the shapes in the sky are actually, in a sense, temporary. The fact that we see them at all is dependent on our perspective in time and space, because the universe is constantly shifting and changing. If we had popped into being at another time or place, the stars would look completely different to us. And while the stars that make up constellations appear close together, in most cases their actual positions in space arent close at all. We might see them as flat, but the stars, of course, exist in three dimensions. If you could shift your point of view by traveling to a different star, you wouldnt recognize any familiar constellations.

Its hard to fathom the fact that these star shapes, which seem like such fixed parts of our world, are, on a cosmic time scale, fleeting. We dont like to be reminded of our temporary nature, so we cling to the constants that seem surest. When we look up, we want to recognize what we see. And so far, we have been able to do just that.

The time scale of humanity is tiny in comparison to the scale of the universemodern humans have existed for only about 200,000 years, while the universe is currently estimated to be 13.8 billion years old. The stars have been moving, but so slowly that to us they seem to have hardly moved at all. Our solar system has been moving slowly too. But still, as far back as we can remember, the constellations have looked the way they do today.

In astronomy, the term constellation actually refers to the area within a boundary drawn around that section of the sky, not the actual bright group of stars recognizable to the naked eye. Astronomers call those bright groups asterisms . Manyif not mostconstellations contain asterisms of the same name (the constellation boundary of Orion contains one bright star shape: that of Orion the hunter). Other constellations contain recognizable asterisms within their boundaries (the constellation Ursa Major contains the asterism of the Big Dipper).

Though easily recognized asterisms like the Big Dipper can be helpful in orienting yourself as you look at the sky, in this book we will be focusing on the constellations defined by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). These are the boundaries astronomers use to describe where in the sky any particular phenomenon appears, and they encompass the entire sky.

The constellations serve us as a sort of map legend; we have assigned every star that can be seen from Earth, whether visible to the naked eye or with a telescope, to a particular constellation. Other space phenomena are assigned to constellations as wellan astrophysicist might refer to a nebula in the constellation of Taurus or an exoplanet in the constellation of Pegasus. Even though we cant see these deep-space objects with our naked eye, we can locate the boundaries of their constellations.