Leonardo da Vinci - Leonardo on the Human Body

Here you can read online Leonardo da Vinci - Leonardo on the Human Body full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Dover Publications, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Leonardo on the Human Body

- Author:

- Publisher:Dover Publications

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Leonardo on the Human Body: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Leonardo on the Human Body" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

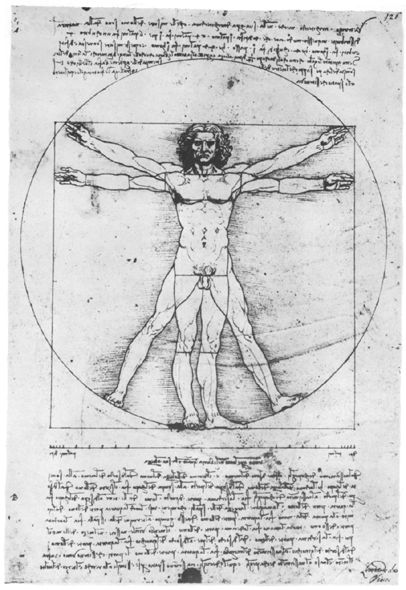

Here are clear reproductions of over 1,200 anatomical drawings by one of humanitys greatest geniuses still considered, nearly five centuries later, the finest ever rendered. With 215 plates, including studies of the osteological, myological, nervous, respiratory, alimentary, and genito-urinary system, this treasury will be admired by artists and scientists alike.

Leonardo on the Human Body — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Leonardo on the Human Body" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

LEONARDO DA VINCI

Translations, Text and Introduction by

CHARLES D. OMALLEY, Stanford University, and

J. B. DE C. M. SAUNDERS, University of California

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC., NEW YORK

This Dover edition, first published in 1983, is an unabridged republication of Leonardo da Vinci on the Human Body : The Anatomical, Physiological, and Embryological Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci , originally published by Henry Schuman, New York, 1952.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519.

Leonardo on the human body.

Reprint. Originally published: Leonardo da Vinci on the human body. New York: H. Schuman, 1952.

1. Anatomy, HumanEarly works to 1800. I. Title.

QM21.L53 1983 611 82-18285

ISBN 0-486-24483-0

THE AUTHORS WISH TO EXPRESS THEIR PROFOUND GRATITUDE FOR THE MOST GRACIOUS PERMISSION OF HER MAJESTY, QUEEN ELIZABETH II FOR THE USE OF THE REPRODUCTION OF THE LEONARDO DA VINCI DRAWINGS AT WINDSOR CASTLE. WE WISH ALSO TO EXPRESS OUR GRATITUDE TO SIR OLIVER FRANKS, BRITISH AMBASSADOR TO THE UNITED STATES AND MR. J. MITCHESON, H. B. M., BRITISH CONSUL GENERAL AT SAN FRANCISCO FOR THE KINDNESS THEY HAVE SHOWN IN THIS MATTER.

acknowledgments

In the assembling and editing of this work we found the extraordinary Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana of Los Angeles most helpful and cooperative. Profound thanks are also due to The Burndy Library of Norwalk, Conn., which provided the source works from which these anatomical drawings were reproduced.

CHARLES D. OMALLEY

J. B. de C. M. SAUNDERS

CONTENTS

plate number

If it may be said that the fourteenth century ushered in a new period of civilization, for convenience called the Renaissance, then it may be remarked that anatomy in that new age was long to remain mediaeval, at least insofar as it was reflected in medical illustration. Prior to this new era the teaching of anatomy had been based largely upon the dissection of animals, but in the thirteenth century even this limited procedure of direct observation was largely superseded by the Arabic influence which led to efforts to teach anatomy wholly from textbooks. Although the Arabic influence was to be cast off eventually, yet anatomy was still to suffer from strictures arisen from a misunderstanding of the position of the church. In 1300 Pope Boniface VIII had issued a bull, De sepulturis , which proclaimed excommunication for any who should follow the practice of boiling the bones of persons, in particular crusaders, in order to make their storage and transport easier for burial at home. This bull was frequently and incorrectly interpreted, even by anatomists, as a prohibition against dissection. Partly perhaps as an outgrowth of this situation and partly as the result of too literal religious views there was also considerable popular opposition to dissection of the human body for fear of the consequences upon resurrection.

Despite such obstacles there was a limited knowledge of anatomy, partly traditional, partly the outgrowth of surgical experience and very likely from time to time the reflection of surreptitious dissection. The first open mention of dissection was of one performed in Italy in 1286. However, it was nothing more than a post-mortem examination of a victim of a pestilence then raging and was for the purpose of attempting to find the cause of death. There is a more formal account of an examination performed in 1302 in Bologna to ascertain the cause of a death which had occurred under suspicious circumstances. The account does not suggest the procedure as unusual and presumably post-mortem examinations as legal devices had previously been performed. Yet such examinations would yield little anatomical information since normally the procedure required little more than the opening of the thorax and an examination of the contents.

With the appearance in 1316 of the A nothomia of Mundinus (c.1270-1326) we enter upon what might be called the non-mediaeval rather than the modern period of anatomy. Moreover, it should be emphasized that in this period anatomy was considered to include both a knowledge of the structure and of the function of the human body. Mundinus book is the first devoted entirely to this subject, and although the Arabic tradition is still strong, yet it is obvious that Mundinus incorporated the results of dissection and, indeed, performed the dissections himself. From the time of Mundinus the medical school at Bologna was to become the centre of such anatomical knowledge as there was. There dissection was officially recognized by university statute in 1405, to be followed in 1429 by a similar recognition at Padua. However, permission did not necessarily imply opportunity, and cadavers were only very infrequently at the disposal of the schools. Furthermore, the successors of Mundinus for the next century and a half did little more than echo and confirm what he had already propounded, and this is not to be wondered at in view of what passed for dissection.

This limited interest in anatomy is supported by text and illustration, although the situation is more precisely defined in the former since it was not until the sixteenth century, and even then far from unanimously, that physicians came to look upon correct anatomical drawings as having any pedagogical value. Indeed, many physicians up to this time decried the employment of anything which might tend to distract the reader from the text. Under such conditions, it is not astonishing to find that illustration displayed no development. Such as there was remained traditional, often having no immediate relationship to the text and frequently merely a kind of symbolic decoration. Thus to judge the anatomical knowledge at any given time from such illustrative material would be wholly misleading.

The major tradition insofar as anatomical illustration is concerned was one which is said to go as far back as the time of Aristotle who in his De generatione animalium , I:7, speaks of the teaching of anatomy through paradigms, schemata and diagrams. Thereafter the Alexandrian anatomists such as Herophilus and Erasistratus are said to have continued the employment of such sorts of illustrative materials in their teaching.

While it is impossible to say precisely what these illustrative materials were, nevertheless there is fairly general support for the belief that what Karl Sudhoff called the Five Picture Series represents a portion of them. These five views, representative of the bones, muscles, nerves, veins and arteries, and displayed in crude human figures, invariably in a semi-squatting position, have been found not only in Europe and Asia, but also in the western hemisphere. The similarity of posewith full anterior view of body and face, the latter completely rigidsuggests a longstanding tradition which Sudhoff considers as indicating characteristics of early Egyptian and Greek sculpture and therefore supporting a Hellenic and Alexandrian origin.

Through successive centuries the tradition appears to have remained constant with the exception that occasionally a sixth figure was added, either a view of the pregnant woman or depiction of the generative organs, either male or female. However, the anatomical content of the series passed on to successive centuries without change despite the fact that anatomical texts indicate gradually increasing knowledge. It is not astonishing therefore that as anatomical knowledge increased, notably at the end of the fifteenth century, this series of five or six crude figures is less and less associated with the physician and becomes a device to assist the unlearned barber-surgeon in his activities, especially that of bloodletting. Nevertheless the pedagogical aspect of the tradition associated with the figures continued in regular medical circles. Thus the Tabulae anatomicae of Vesalius (1538) are the result of this influence although the new pose of the figures, the superior draughtsmanship and far more nearly correct anatomy represent a novelty.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Leonardo on the Human Body»

Look at similar books to Leonardo on the Human Body. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Leonardo on the Human Body and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.