Leonardo da Vinci

The domain of biography, too, must become ours. The riddle of Leonardo da Vinci's character has suddenly become transparent to me. That, then, would be the first step in biography.

Sigmund Freud, letter to Carl Gustav Jung, October 1909

Freud's Leonardo changed the art of biography forever. Henceforth none would be complete without a rummage through the subject's childhood origins.

Oliver James

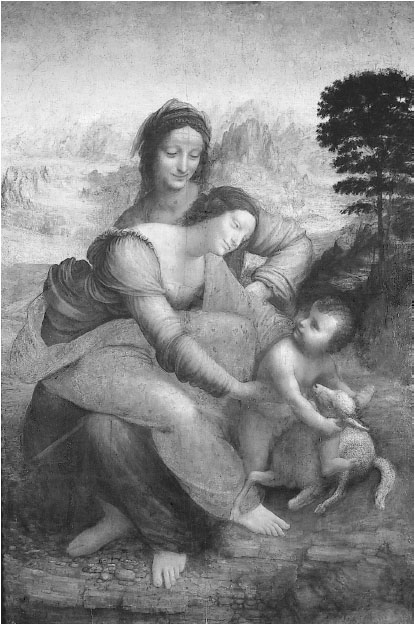

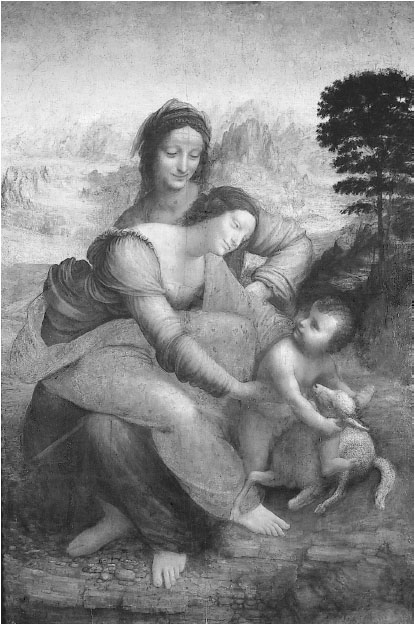

Leonardo's Madonna and Child with St Anne. Photo Scala, Florence.

Sigmund

Freud

Leonardo da Vinci

A memory of his childhood

Translated by Alan Tyson

| London and New York |

First published 1910 by Deuticke

English edition with Preface by Ernest Jones first published in the United Kingdom 1922 by Kegan Paul

This translation first published 1957

by Routledge and Kegan Paul as part of the International Library of Psychology

First published in Routledge Classics 2001

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1957 The Institute of Psycho-Analysis and Anna Richards

Typeset in Joanna by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN10: 0415253861 (pbk)

ISBN13: 9780415253864 (pbk)

Preface to the 1922 Edition

With a book already so well-known little seems needed by way of Preface. It is a brilliant example of the way in which knowledge based on the detailed psycho-analysis of living persons can be made use of to throw light on the deeper springs of character in those whose mind is not accessible to direct investigation. The process is, therefore, akin to a piece of archaeological reconstruction. The study is based on the solitary mention Leonardo makes of his childhood, evidence which most psychologists would have passed by as being flimsy and meaningless; but its unique occurrence and extraordinary nature both call for explanation, if we are not to dismiss such happenings as being causeless. Professor Freud has dealt with it by comparing it with similar phantasies analysed by him and with other known facts of Leonardo's life. In the fascinating study resulting from this procedure he has thrown a flood of light on one of the most remarkable and interesting personalities of history.

Ernest Jones.

December, 1921.

EDITOR'S NOTE

EINE KINDHEITSERINNERUNG DES

LEONARDO DA VINCI

(a) German Editions:

1910 Leipzig and Vienna: Deuticke. Pp.. (Schriften zur angewandten Seelenkunde, Heft 7)

1919 2nd ed. Same publishers. Pp..

1923 3rd ed. Same publishers. Pp..

1925 G.S., , 371454.

1943 G.W., , 128211.

(b) English Translation:

Leonardo da Vinci

1916 New York: Moffat, Yard. Pp. 130. (Tr. A. A. Brill.)

1922 London: Kegan Paul. Pp. v + 130. (Same translator, with a preface by Ernest Jones.)

1932 New York: Dodd Mead. Pp. 138. (Re-issue of above.)

The present translation, with a modified title, Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood, is an entirely new one by Alan Tyson.

That Freud's interest in Leonardo was of long standing is shown by a sentence in a letter to Fliess of October 9, 1898 (Freud, 1950a, Letter 98), in which he remarked that perhaps the most famous left-handed individual was Leonardo, who is not known to have had any love-affairs.n. After reading this and some other books on Leonardo, he spoke on the subject to the Vienna Psycho-Analytical Society on December 1; but it was not until the beginning of April, 1910, that he finished writing his study. It was published at the end of May.

Freud made a number of corrections and additions in the later issues of the book. Among these may be specially mentioned the short footnote on circumcision (p. n), added in 1923.

This work of Freud's was not the first application of the methods of clinical psycho-analysis to the lives of historical figures in the )reflections which have a general application even to-day to the authors and critics of biographies.

It is a strange fact, however, that until very recently none of the critics of the present work seem to have lighted upon what is no doubt its weakest point. A prominent part is played by Leonardo's memory or phantasy of being visited in his cradle by a bird of prey. The name applied to this bird in his notebooks is nibio, which (in the modern form of nibbio) is the ordinary Italian word for kite. Freud, however, throughout his study translates the word by the German Geier, for which the English can only be vulture.

Freud's mistake seems to have originated from some of the German translations which he used. Thus Marie Herzfeld (1906) uses the word Geier in one of her versions of the cradle phantasy instead of Milan, the normal German word for kite. But probably the most important influence was the German translation of Merezhkovsky's Leonardo book which, as may be seen from the marked copy in Freud's library, was the source of a very great deal of his information about Leonardo and in which he probably came across the story for the first time. Here too the German word used in the cradle phantasy is Geier, though Merezhkovsky himself correctly used korshun, the Russian word for kite.

In face of this mistake, some readers may feel an impulse to dismiss the whole study as worthless. It will, however, be a good plan to examine the situation more coolly and consider in detail the exact respects in which Freud's arguments and conclusions are invalidated.

In the first place the hidden bird in Leonardo's picture (p. n.) must be abandoned. If it is a bird at all, it is a vulture; it bears no resemblance to a kite. This discovery, however, was not made by Freud but by Pfister. It was not introduced until the second edition of the work, and Freud received it with considerable reserve.

Next, and more important, comes the Egyptian connection. The hieroglyph for the Egyptian word for mother (mut) quite certainly represents a vulture and not a kite. Gardiner in his authoritative Egyptian Grammar (2nd ed., 1950, 469) identifies the creature as Gyps fulvus, the griffon vulture. It follows from this that Freud's theory that the bird of Leonardo's phantasy stood for his mother cannot claim direct support from the Egyptian myth, and that the question of his acquaintance with that myth ceases to be relevant. no immediate connection with each other. Nevertheless each of them, taken independently, raises an interesting problem. How was it that the ancient Egyptians came to link up the ideas of vulture and mother? Does the egyptologists explanation that it is merely a matter of a chance phonetic coincidence meet the question? If not, Freud's discussion of androgynous mother-goddesses must have a value of its own, irrespective of its connection with the case of Leonardo. So too Leonardo's phantasy of the bird visiting him in his cradle and putting its tail into his mouth continues to cry out for an explanation even if the bird was not a vulture. And Freud's psychological analysis of the phantasy is not contradicted by this correction but merely deprived of one piece of corroborative support.