Just One More

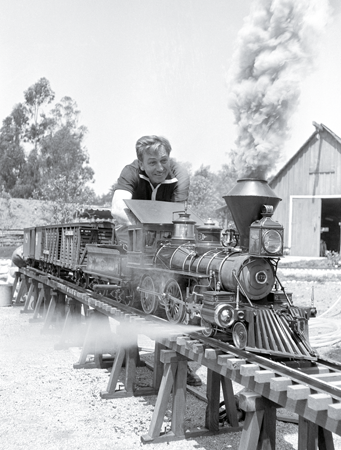

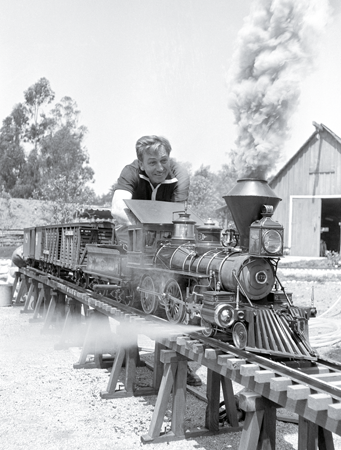

EARL THEISEN/ARCHIVE PHOTOS/GETTY

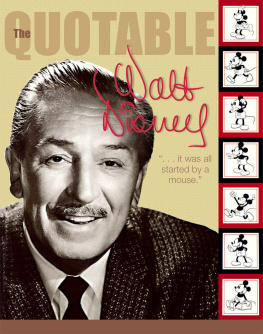

Walt Disney worked on a model train in his backyard circa 1955 in Los Angeles. I always believed the reason Walt built Disneyland was that he wanted . . . the biggest train layout, said Imagineer Bruce Gordon. People would think he was crazy, but he was only playing with his toy.

The Beginnings

How Walt Disneys midlife obsession with miniatures and trains led to the creation of the worlds greatest theme park

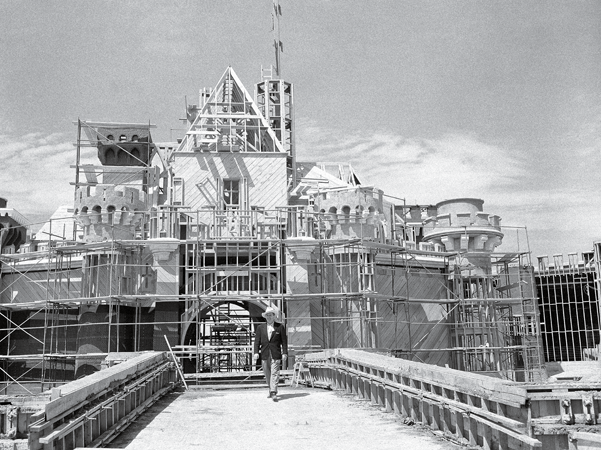

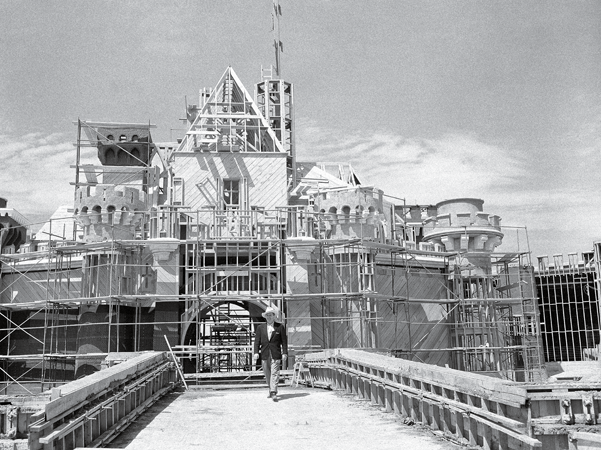

DAVID F. SMITH/AP/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

Walt Disney crossed the drawbridge that serves as the entrance to Sleeping Beauty Castle in the heart of Disneyland, circa 1955. The original site of the castle proved to be overrun with feral cats, which animal lover Disney took pains to save.

It was June 1955only six weeks before Disneyland was scheduled to openand Walt Disney was worried. His risky new park in Anaheim, California, was still a work in progresshardly more than the orange groves it had been built on. From the start, construction had been plagued with problems, including a record deluge of rain. Now Main Street wasnt paved; Sleeping Beauty Castlethe centerpiece of the parkwasnt finished; and Tomorrowland barely existed. Plumbers told Disney that, because of a strike, they couldnt make both the drinking fountains and the bathrooms work. Walt, of course, opted to fix the bathrooms. People can buy Pepsi-Cola, he said, but they cant pee in the street.

The project itself had repeatedly gone over its original budget of $4.5 million. Two months after construction began in July 1954, the cost had risen to $7 million. Then it skyrocketed to $11 million. We were still talking $11 million in April when I was walking down Main Street with [Disneys older brother] Roy and a representative from Bank of America, who scanned the project and said it looked closer to $15 million, said Joe Fowler, the former Navy rear admiral who had been put in charge of the parks construction.

By opening day, the investment had risen to a whopping $17 millionlargely because Disney himself was never satisfied, a personal characteristic that led to a process he called plussing. As he did with his films, the 53-year-old wanted everything to be bigger, better, more surprising, and more innovative. At the last minute, for instance, he decided that he wanted to create an attraction featuring the giant squid from his 1954 hit 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which he helped spray-paint on the night before the openingeven as he continued to micromanage everything else. At three a.m., he was demanding new murals: Get me an artist! he shouted.

But Walt ultimately let gowell, he had toand on the morning of July 17, 1955, Disneyland opened to an overflowing crowd of 28,000 people. Despite the considerable flaws, it was a revolutionary moment in American cultureand the fulfillment of a dream that had begun less than a decade before with, of all things, a model train.

On December 8, 1947, Walt wrote a letter to his sister: I bought myself a birthday presentsomething Ive wanted all my lifean electric train . . . I have set it up in one of the outer rooms adjoining my office so that I can play with it when I have a spare moment. Its a freight train with a whistle, and real smoke comes out of the smokestackthere are switches, semaphores, stations, and everything. Its just wonderful!

The filmmaker had been fascinated by trains ever since his boyhood in Marceline, Missouri, the small town where his father, Elias, moved his family in 1906, having failed as a carpenter in Chicago. Little more than a whistle stop between the Windy City and Kansas City, Missouri, Marceline was nevertheless a bucolic paradise for little Walt, who spent his four short years there prowling Main Street, sketching the animals that populated the family farm, and, not least, marveling at the locomotives. The experience exerted an enduring influence on nearly everything Disney didfrom homey films like Pollyanna to Disneylands Main Street, U.S.A. It was, in fact, the most important part of Walts life, his wife, Lillian, later said.

The youthful idyll didnt last. Times were hard, and Elias was not cut out for farming. In 1911, he once again uprooted his family and moved to Kansas City, where he was reduced to running a paper route. His principle employees were, not surprisingly, his four sons. Little Walt, the youngest, would rise in the predawn darkness and work all dayoften in freezing cold and snow so deep it sometimes reached his neck. Now and then he fell asleep, exhausted, in apartment foyers. But the beleaguered boy nurtured big dreams that reflected the two things that would end up defining his life: escape and control.

Next page