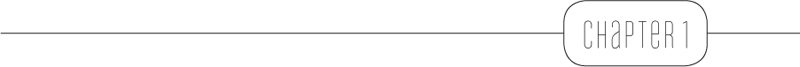

IAIN M. BANKS

MODERN MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION

Edited by Gary K. Wolfe

Science fiction often anticipates the consequences of scientific discoveries. The immense strides made by science since World War II have been matched step by step by writers who gave equal attention to scientific principles, human imagination, and the craft of fiction. The respect for science fiction won by Jules Verne and H. G. Wells was further increased by Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, and Ray Bradbury. Modern Masters of Science Fiction is devoted to books that survey the work of individual authors who continue to inspire and advance science fiction.

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

2017 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kincaid, Paul, author.

Title: Iain M. Banks / Paul Kincaid.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, [2017] | Series: Modern masters of science fiction | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016054031 (print) | LCCN 2016054150 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252041013 (hardback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780252082504 (paperback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780252099564 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Banks, Iain, 19542013 Criticism and interpretation. | Science fiction, EnglishHistory and criticism. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Science Fiction & Fantasy. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary.

Classification: LCC PR6052.A485 Z69 2017 (print) | LCC PR6052.A485 (ebook) | DDC 823/.914dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016054031

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Any number of people deserve to be thanked on a project like this. Singling out a few is always invidious because you risk forgetting the many. However, there are some people who have directly contributed to the work you hold in your hand, and I am delighted to acknowledge their help.

To start with, this would not be the book it is without David Haddock, source of all esoteric knowledge when it comes to Iain Banks. He was encouraging from the start and has provided an unexpected wealth of interviews, essays, letters, books, and other material that would have been all too easy to miss. Without his help, this would have been a much poorer book.

Tony Keen provided unpublished material he has written about Iain Banks, which was invaluable in helping to focus my own ideas. He also read and commented on some of the chapters as they were written, which has helped rescue me from some of the worst sins of my first draft.

Thanks also to Ken MacLeod, who took time out from writing his next novel in order to patiently answer my impertinent, if not downright nosy, questions.

Jude Roberts was generous in allowing me to use her interview with Iain Banks in this book.

And, as ever, I must thank my wife, Maureen Kincaid Speller, copyeditor and proofreader extraordinaire, whose keen eye was essential.

Finally, to everyone whose encouragement or support helped, whether you knew it or not, thank you.

IAIN M. BANKS

CROSSING THE BRIDGE

On April 3, 2013, Iain Banks posted a Personal Statement on the Iain M. Banks website: I am officially Very Poorly. He was typically matter-of-fact about his condition: As a late stage gall bladder cancer patient, Im expected to live for several months and its extremely unlikely Ill live beyond a year.

Ive asked my partner Adele [Hartley] if she will do me the honour of becoming my widow, he continued. They married on March 29, 2013. While the pair had a short honeymoon in Venice and Paris, a host of messages started to appear on social media and on the Banksophilia website set up for the purpose. Returning from holiday, Banks wrote a May 20 update on the site: Ive been reading the posts on the site. So far Ive reached page 60, which is getting on for a third of the way through. Many of these messages related anecdotes about meeting Banks, but the vast majority were from people who knew him only through his books. The novels had forged a personal connection

As that comment suggests, the Culture, which featured in nine novels, a novella, and a couple of short stories, had become for science fiction readers an iconic image, a utopia that was dynamic and liberal. Banks posited a post-scarcity society in which there is no need to work, because all drudgery is performed by AIs; in which there is no money, because anyone can have whatever they desire; in which there are no hierarchies; and in which anyone can become whatever they wishso, for instance, people regularly change sex. Little wonder that, from its first appearance in Consider Phlebas (1987), the Culture acquired a consistent following.

But Banks was not initially known as a science fiction writer. His first novel, The Wasp Factory (1984), which featured murder, madness, and what some regarded as very sick humor, was probably the most controversial literary debut of the 1980s, a book that sharply and violently divided critics. In part because of that controversy, the novel became a bestseller, and his next two novels, Walking On Glass (1985) and particularly The Bridge (1986), which could be his masterpiece, confirmed the appearance of a major talent. Each book was very different from its predecessor, but they shared a narrative vigor, an often black humor, and he managed huge vistas with deft skill.

After The Bridge , Bankss career took an unexpected turn with the publication of Consider Phlebas under a different form of his name: Iain M. Banks. That Banks should write a science fiction novel was not particularly surprisingthere were enough hints in the first three novels to make this a natural progressionbut he chose to write in what was, at the time, considered to be a worn out and generally despised subgenre, the space opera. In doing so, he almost singlehandedly revitalized the form. From that point on he maintained two distinct writerly personas. As Iain Banks he wrote mainstream fiction that varied from the story of a contemporary pop star ( Espedair Street , 1987) to a richly comic novel of a dysfunctional family ( The Crow Road , 1991, with its famous opening sentence: It was the day my grandmother exploded [ Crow , 3]) to a violent crime novel ( Complicity , 1993) to a fable about the effects of war ( A Song of Stone , 1997). These were interspersed with the science fiction of Iain M. Banks, which tended to be novels of the Culture, often displaying daring structural experimentation ( Use of Weapons , 1990; Excession , 1996), though he did occasionally venture outside the Culture, most notably with Feersum Endjinn (1994).

This apparent bifurcation in Bankss career, between the work of Iain Banks and Iain M. Banks, is in fact no less flexible and open to interpretation than the distinction Graham Greene drew between his novels and his entertainments. Nevertheless, it has led to the popular view that, since the novels of Iain M. Banks are overtly science fiction, then the novels of Iain Banks, including those published at the very start of his career, must be mainstream. The distinction, however, is nowhere near so clear-cut. Even before we come to the liminal case of Transition (2009, see

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.